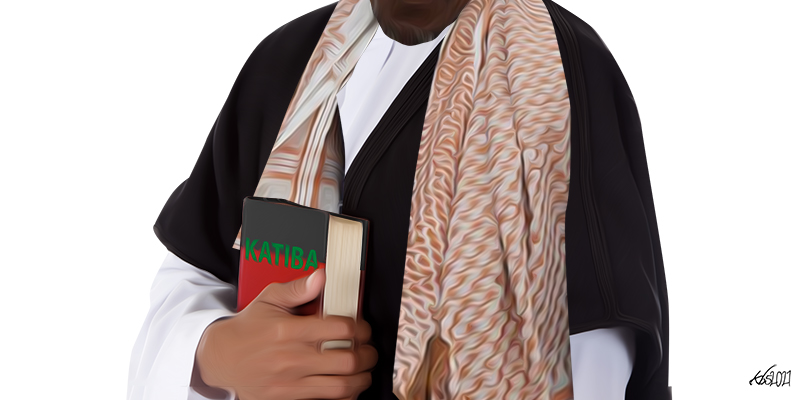

Kenyan post-independence administrations have perpetuated the colonial policy of looking at Northern Kenya through the security lens, and have economically marginalised the region and its people. The 2010 Katiba (constitution) was to be the cure for the decades of marginalisation that the region has suffered. But the national political elite and the local elite are fervently subverting the gains of the Katiba — the national elite via revenue allocation and mischievous delays in providing infrastructure for socio-economic change and development, and the local elite via pilfering and stoking the fires of inter-community hostilities.

Between 2001 and 2010, pastoralists and their representatives and partners participated in the Kenya constitutional review process with unparalleled zeal and tenacity. In their arduous engagement with the constitutional reform processes, pastoralists had reminded themselves that democracy was not a spectator sport but a participatory process. They were convinced that they were on the cusp of change.

While presenting their familiar positions on critical issues that needed inclusion in the new constitution, pastoralists were against an imperial presidency and supported a parliamentary system; they called for affirmative measures in favour of minorities and other marginalised groups; they overwhelmingly supported a devolved structure of government that would bring government services and resources closer to the people and increased participation in decision-making on development priorities by the communities themselves. Above all, they campaigned for a more equitable sharing of national resources.

The 2010 constitution

The promulgation of the 2010 Constitution was a watershed moment for communities in northern Kenya. The constitution provided a solid, legal and institutional framework for recognising and protecting the rights of minorities and marginalised groups. Northern Kenya was essentially reborn. The constitution engendered nothing short of a revolution of rising expectations. The devolved governance in the 2010 constitution was the most pivotal gain of all. The right to self-determination, within the context of Kenya’s sovereignty, protected most of their rights and symbolically promised the end to marginalisation.

But ten years on, the debate is whether devolution and its attendant policy, legal and institutional frameworks, resources, and other infrastructure for socio-economic change —largely meant to have been driven by the national government — has matched the expectations of the pastoralist communities. Are current efforts moving towards “releasing our future potential” — in the manner of the curiously provocative slogan attached to the title of the Sessional Paper on National Policy for the Sustainable Development of Northern Kenya and Other Arid Lands — or elsewhere? That is the question the people of northern Kenya are asking.

Joseph Kalapata, a human rights activist from Isiolo, notes, “We are contending with the reality that we were naive to have expected so much. We now know that northern Kenya was not Saul of Tarsus who fell off the donkey and instantaneously became Paul”.

“There is nothing neither creative nor transformational going on. Every new project is a function of normal progression. Everyone tries to be a tenderpreneur. The common person is worse off,” says Enock Talam, a business consultant based in Kapenguria in West Pokot County.

While pundits on either side of the debate continue trading blows, both the county and national governments are praised or blamed for the perceived good or bad fortunes of northern Kenya since 2010. Whichever the case, the foremost responsibility and general mandate of both levels of government is to provide for citizens’ well-being through the equitable and accountable provision of services (Objectives of Devolution, Art. 174). This should be pursued within the inter-dependency, consultation and collaboration between both levels of government, particularly in those sectors in which they share responsibilities (the so-called concurrent functions).

Despite the many policies meant to bring out a favourable socio-economic change in the region, northern Kenya’s longitudinal biography stubbornly yields the historical portrait of an impoverished and underdeveloped region that is lacking in infrastructure and essential services and where governance and the rule of law are at their lowest. The population has suffered decades of economic, political and social marginalisation; disenfranchisement of rights, droughts, conflicts and decreasing resilience characterise the region (Truth Justice and Reconciliation Commission Report).

What has devolution fulfilled?

When assessing the governance and development situation in the region, especially in Marsabit County, scholar Ibrahim Harun (2019) avers that the devolved system of government has radically transformed the previously forgotten Northern Frontier District (NFD), that it has brought government closer to the people and provided democratic and development gains. Additionally, it has forged the inclusion of previously marginalised communities into the political system and that local solutions have been found for local problems. Harun cites Marsabit County government’s expansion of functions, such as agriculture, health services, transport, cultural activities, education, and public works and services.

Northern Kenya’s longitudinal biography stubbornly yields the historical portrait of an impoverished and underdeveloped region.

Ibrahim Harun’s findings reflect the changes that have taken place in most of the counties in northern Kenya — that the devolved system of governance is beginning to make a major difference in a region that presents formidable challenges when it comes to service delivery based on years of marginalisation, distance, population density and division. For optimum service delivery and socio-economic change, these factors still must be dealt with.

Education opportunities

The Constitution of Kenya states that every child has a right to free and compulsory basic education (Article 53 (1) (b)). Delivery of education services in pastoralist countries has improved since devolution was introduced. In their research, Rare and Ombui observe that historically, non-responsive national plans for education, non-existent school infrastructure in remote areas, the vastness of arid lands, cattle rustling, and the severe shortage of teachers — with teachers from other regions unwilling to move to northern Kenya due to insecurity — are some of the factors that have impeded access education. With the devolution of pre-primary and primary education, however, northern Kenya counties have expanded opportunities in education. These include positive developments in early childhood education in Marsabit.

Rare and Ombui report that the health sector has improved greatly under the devolution. Many of the counties have built new health centres, increased medical insurance cover for county workers, upgraded facilities in their referral hospitals with, for instance, operational renal units, and increased allocation to the health sector to about 30 per cent of the gross county revenue (in the case of Marsabit). There has been an increase in the number of health personnel from 330 in 2015 to 623 in 2019 (2018 to 2022 CIPD report) and Kenya Medical Training Colleges have been opened in the region.

Water provision

To achieve equitable development in Kenya, water provision must be a priority. This is because water availability impacts heavily on development of agriculture, health, industry, livestock production, and the pattern of settlement in the region. Northern Kenya counties, the national government and the private sector recognise that the northern region suffers from lack of surface water supply. It lacks lakes, permanent rivers, and streams. Rainfall is at best erratic. For instance, in West Pokot County, distances to water points average five kilometres during seasons of low rainfall. To improve water availability, more irrigation projects are being developed in various counties of northern Kenya. These include Malkadaka, Kinna-Rapsu, Bute-Gurar, Garfasa and Merti. Water harvesting techniques such as roof water harvesting are being promoted.

Infrastructure

For producers from northern Kenya, access to national, regional and international markets is hampered by the vastness of the region, low population density and poor infrastructure (Social Economic Blue Print). It is for this reason that it was quite a relief that the 505km stretch between Isiolo, Marsabit and Moyale was completed and launched. The road has reduced travel time between Moyale on Kenya/Ethiopia border to Nairobi from 60 hours to 8 hours. The Nairobi-Thika-Mwingi-Garissa-Liboi (the border town with Somalia), Mombasa-Malindi-Garsen-Hola-Garissa-Modogashe-Wajir-Elwak-Mandera, and Isiolo-Modogashe-Wajir-Elwak-Mandera corridors are under construction while the Kapenguria-Lokichoggio road is being rehabilitated.

The Masol Integrated Project in West Pokot County is one example of the attempts being made to improve the life of the marginalised pastoralist communities. The multi-pronged project that targets the most marginalised ward includes a school administration block; construction of an eight-classroom block and hostel for the primary school; construction of an equipped modern health centre; drilling of a solar-powered borehole and construction of the Srumben-Koposes road.

Pan-pastoralist planning

Through the Northern Rift Economic Bloc (NOREB) and the Frontier Counties Development Council (FCDC), counties have developed strategies to improve resource mobilisation, trade, and investment in their region. In a fresh approach to realising positive socio-economic change in their region, FCDC members (Mandera, Marsabit, Garissa, Isiolo, Tana River, Samburu, Baringo, West Pokot and Turkana) launched a Social Economic Blueprint for the Frontier Counties Development Council 2018-2030.

The blueprint adopts a new way of analysing the social-economic situation of the north but also what needs to be done to effect change. Policy instruments proposed by the blueprint are based on a geographical model. This geographical model emphasizes the need to approach the policy and intervention opportunities and challenges through the realities of northern Kenya’s low population density, costly distances, and deep divisions. For goals to be achieved, the blueprint highlights a combination of policy instruments with targeted interventions such as institutions and connective infrastructure.

Challenges

As Paul Goldsmith noted, the adoption of the 2010 constitution set the stage for a new phase of transformational reorganisation, allowing Kenyans greater scope in defining their future. But the critical thinking required to guide the transition has lagged far behind. County governments need to upscale their capacity to promote inclusive governance, accountability, and transparency. Social accountability continues to be treated with suspicion by both national and county officers and leaders. Kenyan citizens are frustrated from exercising their sovereignty by holding their leaders accountable on budget processes, public procurement, amongst others. As for effective public participation in planning meetings — which is far from encouraged — feedback on the communities’ proposals is rarely given.

Cynics perceive northern Kenya as a political theatre that reflects the national political environment, where politics is based on ethnic/clan bloc voting. Political contestation is primarily over group claims to and control over key resources, including land, employment, and state revenues. Elected governors are often viewed locally as partisan – as representatives of their clans or tribes, whose principal obligation is to advance the interests of their communal group, and not those of the county population as a whole. They note that fault lines are widening, pitting new elites on one hand and the general population on the other hand. When the scheming of the elites coincides with ethnic, or clan blocs — often presented as coalitions — this threatens the eruption of armed conflict. Goldsmith warns that, “Elite-driven opportunism has suffocated intellectual debate and multicultural vibrancy that once characterised the flow of ideas in this part of the world.”

County governments need to upscale their capacity to promote inclusive governance, accountability, and transparency.

Patronage-based politics and corruption have created new winners and losers at the local level, which has widened existing social cleavages and, and at worst, created new fault lines of conflict. Influential clan members, such as political leaders, often manipulate clan identities and existing cleavages in their pursuit of power and control of resources. The 2014 violence in Mandera County was attributed to competition between the majority Garre and minority Degodia communities. The Degodia accused the Garre of planning to create a “political monopoly in the county”. The local leadership was accused by the County Commissioner of fuelling the Garre-Degodia feud.

In the Social Economic Blueprint, governors agree that socio-economic and developmental change is curtailed ‘’where social, religious and political barriers, such as political conflicts, lack of cohesion and in security, hinder communities from benefiting from socio-economic integration in the FCDC region”. These barriers include ethnic and inter-clan conflicts, conflicts over resources, livestock theft and banditry, radicalisation of youth by Al-Shabab and other insurgent groups, and negative social and cultural practices, such as early and forced marriage of the girl child, Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) and low commercialisation of livestock farming.

On the ground

While the national government has recognised through many of its policy, legal and strategic structures that northern Kenya and other arid lands have suffered historical injustices and marginalisation, and proceeded to endorse affirmative measures for redress, it has yet to fulfil its promises.

The fact that many of the promises made have not been acted upon leads to suspicion that the government is not keen on revitalising northern Kenya. For instance, for a long time many governors across the country had almost believed that the constitution and associated legislations were not sufficient to “prevent the recentralisation of power by the national government”.

Persistent delays in the disbursement of funds to the counties have often led to the national government being accused of frustrating the efforts of the county administrations and the people. As the former Council of Governors chairman Wycliffe Oparanya observed, delaying the disbursement of funds to pay for salaries, health, agricultural extension and development salaries, health, agricultural extension services, and development affects the provision of county services to the public.

The Commission on Revenue Allocation (CRA) classifies northern Kenya counties as “marginalised” areas which should therefore be beneficiaries of the Equalization Fund. The Equalization Fund was established under Article 204 of the Constitution and was aimed at bringing the delivery of services in the marginalised counties to the level enjoyed by the rest of the country by financing such services as roads, water, electricity, and health. Since 2013, marginalised counties have not received monies from the Equalization Fund through the national treasury. In March this year, Business Daily quoted the National Treasury Cabinet Secretary Ukur Yatani saying that a multi-agency committee had handed in the Draft Public Finance Management (Equalization Fund) Regulations to the Cabinet for approval. Once approved by the Cabinet, and certified by the Attorney General, the draft regulations were to be submitted to Parliament for adoption.

Patronage-based politics and corruption have created new winners and losers at the local level, which has widened existing social cleavages.

The Kenya Vision 2030, for instance, proposed the development of resort cities in the FCDC region which ten years later have not been started. The resort cities have yet to take off. Such failures to implement flagship projects do not bode well for the development aspirations of marginalised regions.

Pastoralist communities are still being ravaged by drought emergencies yet the national government which has the responsibility to coordinate and marshal resources towards a durable solution to this challenge has been unable to do so.

The narrative being bandied around that, “they got devolution and it’s all up to them’’, while partially valid — for northern Kenya people must chart the course of their own future — one must be aware of the mischief of reductionism. Northern Kenya’s governance and socio-economic performance is as much its citizens’ business as it is that of all other Kenyans. One cannot fail to grasp the enormity of the marginalisation that the region has gone through. Secondly, this attitude towards northern Kenya ignores how the enduring, complex and structural relations between the centre and the periphery impact performance. In any case, after attaining self-governance in 1963, like other developing countries, Kenya is still struggling with the realities of the embedded linkages between the centres of the West and the peripheries of the developing world, some arguably designed to outlast imperialism.

The devolved system of governance is turning around the fortunes of northern Kenya counties, albeit at a slower pace than had been expected. While the national government should keep its promises for northern Kenya, county governments should preside over institutions that are inclusive, accountable, and transparent.

These counties should avoid situations that might lead to conflict and insecurity. “Unless we watch out, each day could turn out to be an anniversary of a funeral”, says Enock Ripko, a business and Peacekeeping consultant from Kapenguria in West Pokot.