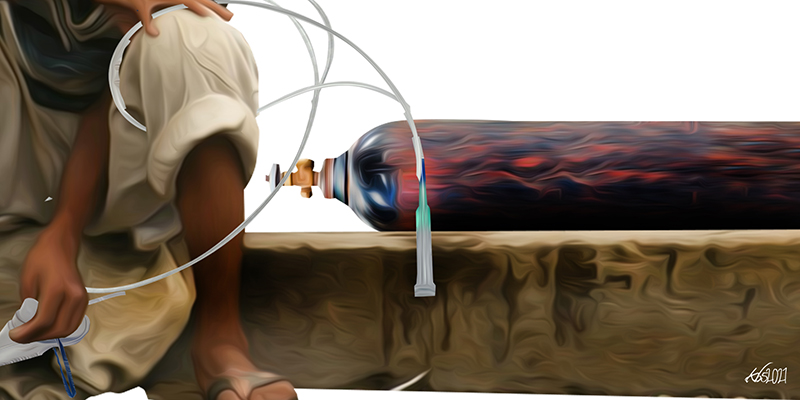

Most of us have seen images of the calamity taking place in Indian cities – overflowing crematoriums; countless burning bodies on wooden pyres; smoke from the flames engulfing entire neighbourhoods; COVID-19 patients dying outside hospitals or in ambulances due to lack of hospital beds or oxygen cylinders. The visuals are compelling, and Indian and international TV channels have not spared any aspect of this unfolding tragedy from being aired on television. CNN even sent their international war correspondent to New Delhi – not their health or science correspondent – which speaks volumes.

There is no doubt that the dramatic spike in COVID-19 deaths in India in the last couple of weeks is a catastrophe that could have been avoided. Analysts have pointed to complacency on the part of both Indians and their government in allowing strains of the coronavirus to spread at crowded political rallies and at the recent Kumbh Mela festival, the largest religious gathering in the world. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has even been accused by Indian activist Arundhati Roy of allowing this “crime against humanity” to take place.

But the images being shown on international television channels are making many Africans uncomfortable. Africans know what it means to be the object of what many perceive as “disaster porn” – a voyeuristic peek (in the name of “news”) into the dying moments of those suffering from a disaster. Now Indians are getting the same treatment.

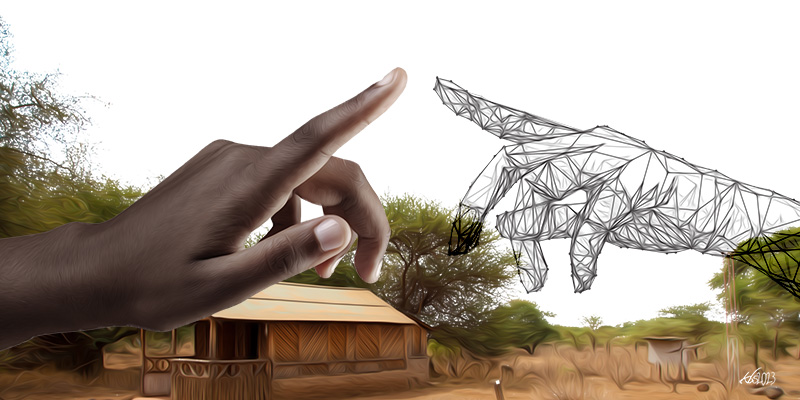

For decades, the world has been fed images of Africans dying from conflict, famines, and other calamities. The photo of the “starving African baby” often appears on the front pages of leading newspapers in the West. Editors argue that such images save lives because they usually lead to a humanitarian response. But Africans know that these images belie a racism that is not immediately apparent because it is often couched in the language of compassion. They know that if the person dying was an American or a European, he or she would not be filmed or photographed in this way because it would rob them of their privacy and dignity. This is why we never saw the mass funerals of Italians when the coronavirus pandemic was at its peak in Italy. Nor did the world see the bodies of the 3,000 Americans who plunged to their death or were burnt alive during the horrific World Trade Centre twin towers terrorist attack on 11 September 2001.

The disaster unfolding in India is one that Western journalists had prepared for, but which did not materialise – until now. As one person on Twitter quipped, the high COVID-19 infection and death rates in the United States and Europe robbed Western journalists of an opportunity to portray it as a Third World problem. Everyone, from billionaire philanthropist Bill Gates to the United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, had predicted that millions of Africans would die from the virus, and they were all geared up for a fundraising campaign for the continent. But on this one, Africans disappointed them; they just did not die in sufficient numbers. India has now given Western journalists an opportunity to focus their voyeuristic gaze elsewhere.

Africans know that these images belie a racism that is not immediately apparent because it is often couched in the language of compassion.

Various theories about why Africans are not getting infected in large numbers have been proposed, including Africa’s youthful population that is apparently disease-resistant, Africa’s largely rural population,which has more exposure to fresh air, and so is less likely to inhale the virus, and the continent’s hot climate, which is not conducive to the virus’s longevity (even though not all of Africa has high temperatures; many parts of the continent experience near-zero temperatures in the winter).

This “othering” of non-white people is also reflected in COVID-19 reporting. Indi Samarajiva, writing in The Medium, talked about a New York Times article where a journalist wondered whether “there is a genetic component in which the immune systems of Thais and others in the Mekong River region are more resistant to the coronavirus”. Samarajiva called this racist reporting. “Instead of looking at what the Thai people did, they’re asking if it’s something in their veins. Because Thai people couldn’t possibly just be competent, it must be alchemy,” he wrote.

The number of fatalities in African countries is in sharp contrast to the massive death toll in the United States, where millions have been infected and where more than half a million people have died from the disease, making America the country with the highest number of COVID-related deaths. If such horrifying figures were emanating from the African continent, there would no doubt have been a massive fundraising drive for Africans. Even televised images of thousands of middle-class Americans lining up for food donations and food stamps did not prompt international charities to organise a fundraising campaign for America’s hungry and jobless citizens.

Few analysts and media houses have dared to admit that some African countries might actually have been better at handling the pandemic than countries such as the United States, Britain, and Italy, where governments did not impose stringent measures on citizens to contain the virus. Uganda, Senegal and Rwanda, which successfully contained the virus in the initial stages through a series of rigorous measures and strategies, were not hailed as success stories in the fight against COVID-19. Nor did we hear much about Vietnam, where only a few dozen people died from the virus in the early months of the pandemic.

Kenyans have in the past called out racist depictions of tragedies occurring in their country. After the Al Shabaab terror attack on the Dusit D2 building in Nairobi in January 2019, which left 21 people dead, the New York Times carried a disturbing photo of dead bodies slumped over dining tables in a restaurant in the building. Kenyans on Twitter (KOT) reacted quickly and furiously. Under the hashtag #SomeoneTellNYTimes, many Kenyans argued that the newspaper had employed double standards – that if the images were of dead Americans, they would not have been published. Despite the protests, the New York Times refused to pull down the offending photo. Instead, it issued an unapologetic and defensive statement that said that the newspaper believed “it is important to give our readers a clear picture of the horror of an attack like this”, which “includes showing pictures that are not sensationalized but that give a real sense of the situation.” The statement further said that the newspaper takes “the same approach wherever in the world something like this happens – balancing the need for sensitivity and respect with our mission of showing the reality of events.”

India has now given Western journalists an opportunity to focus their voyeuristic gaze elsewhere.

The self-righteousness reflected in this statement reminded me of a photo essay published by TIME magazine in June 2010 that showed the dying moments of an 18-year-old Sierra Leonean woman called Mamma Sessay who had just given birth to twins in a rural clinic. Ten images captured Sessay’s slow and painful death as she struggled to give birth to the second twin, nearly 24 hours after giving birth to the first. It was as if the photographer anticipated her death, and decided to watch it happen before his eyes. He did not take Mamma to the nearest hospital or offer any other kind of help. As one Kenyan female blogger commented: “Here, the author and the photographer strip Mamma of all dignity, parading her in her very desperate moments for the world to see. Would these pictures have been published if she was white?”

Why is death considered a private, sombre affair when the person dying or who has died is white but a public event if the person who is dying or is dead is black or brown? It his high time the international media stopped using this double standard in its reporting of grim news.