[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Stashed inside pickup trucks and guarded by armed militias and jihadists, every year billions of illicit cigarettes wind their way through the lawless deserts of northern Mali bound for the Sahel and North Africa.

The profits from their long journey fuel north Mali’s many armed conflicts, lining the pockets of offshoots of al-Qaida and the so-called Islamic State (IS) group, as well as local militias, and corrupt state and military officials. This violence is now spilling out across West Africa, displacing more than two million people in Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, and Niger.

Cigarettes made by one of the world’s largest tobacco companies, British American Tobacco (BAT) and distributed with the help of another major, Imperial Brands, through a company partially owned by the Malian state, dominate this dirty and dangerous trade.

Now an investigation by OCCRP can show this is no accident.

Secrets contained in leaked documents, backed up by trade data and dozens of interviews with insurgents, former BAT employees, experts, and officials, show BAT started to oversupply Mali with cigarettes soon after the north fell to militants, knowing that its product would be fodder for traffickers.

The profits of cigarette smuggling fuel the bloody struggle between jihadists, armed militias, and corrupt military officers that has turned northern Mali into a lawless warzone.

For years the company partnered with Mali’s state-backed tobacco company, a subsidiary of Imperial Brands, to distribute cigarettes in regions controlled by rebel militias and throughout the country. Sources say these cigarettes, trucked north with the help of the military and police, then fall into the hands of jihadists and militias. An internal document suggests BAT used informants in West Africa to keep abreast of the workings of the illicit trade.

The dirty business goes well beyond the desert. OCCRP’s reporting found the Malian government not only helps to distribute BAT’s cigarettes, but also apparently turns a blind eye to gross accounting irregularities at its partner Imperial and even possible trade fraud.

And it continues today. Public trade data and expert analysis show BAT and Imperial continue to oversupply the country with billions more cigarettes than it needs. Meanwhile, BAT’s annual revenue in 2019 alone exceeded the total GDP of Mali and Burkina Faso.

The Malian case is the latest to show the world’s leading tobacco companies are not always abiding by the terms laid out in a series of historic agreements between 2004 and 2010 with the European Union (EU), in which they agreed to prevent their cigarettes from falling into the hands of criminals by only supplying legitimate demand. The agreements were concluded in the wake of legal disputes between three companies and the EU over cigarette smuggling.

“This is their playground,” Hana Ross, a University of Cape Town economist who researches tobacco, said of the industry.

“They know they can get away with stuff. It’s much easier to bribe. It’s much easier to cheat the system,’’ she said. “Governments here are generally weak. This is where they do things that they don’t dare to do in Europe anymore.”

A spokesperson said BAT was opposed to the illegal trade in tobacco, which the company called a “serious, highly organized crime.”

“At BAT, we have established anti-illicit trade teams operating at global and local levels. We also have robust policies and procedures in place to fight this issue and fully support regulators, governments and international organizations in seeking to eliminate all forms of illicit trade.”

BAT started to oversupply Mali soon after the north fell to militants, knowing its product would be fodder for traffickers, according to dozens of interviews.

Imperial said it is committed to ensuring high standards of corporate governance and “totally opposed to smuggling which benefits no-one but the criminals involved.”

The Malian government did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

The Tobacco People

In the deserts of northern Mali, cigarette smugglers are called “kel tabac,” the tobacco people.

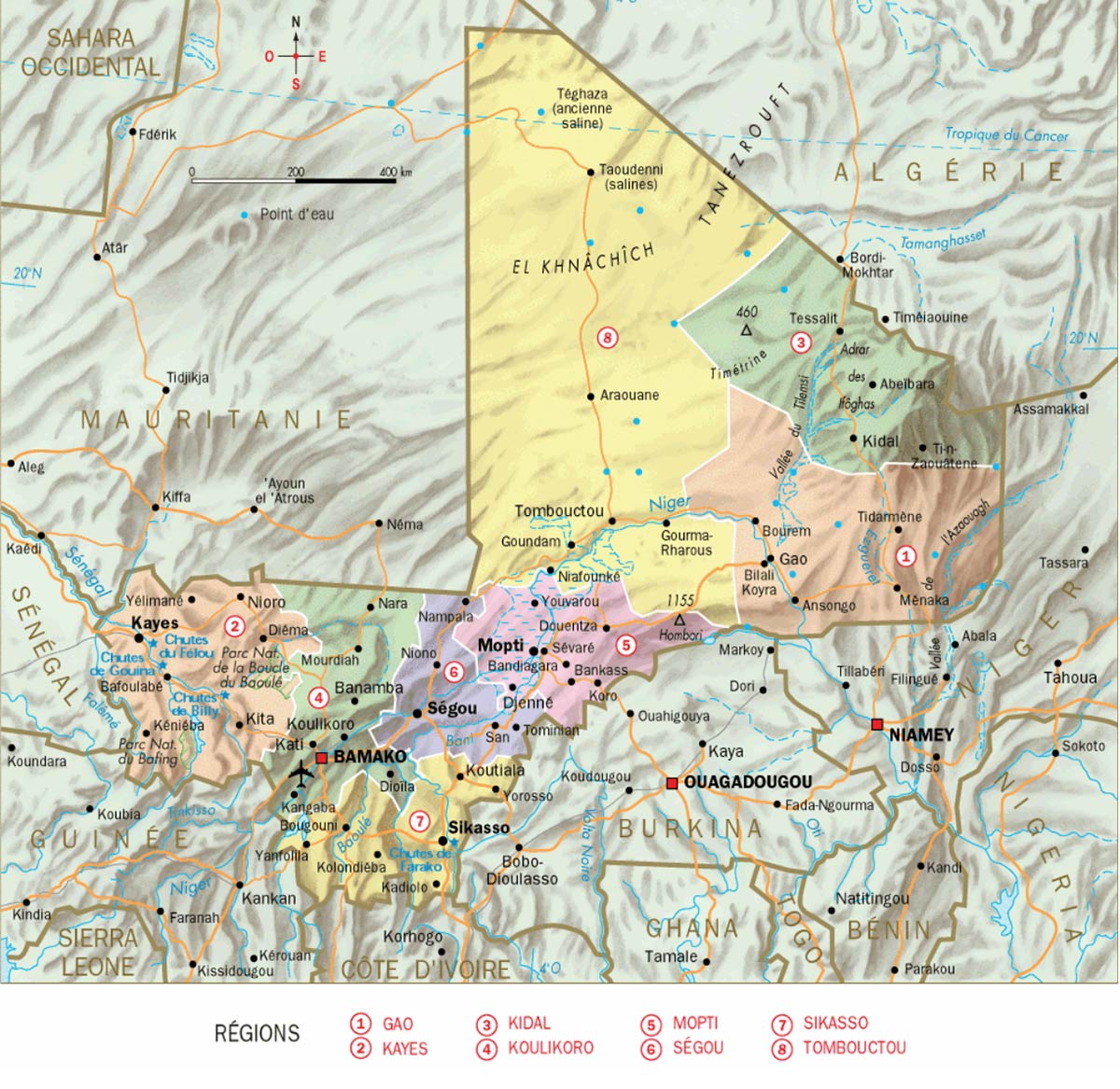

Illicit cigarettes from the capital, Bamako, and ports in Guinea, Benin, and Togo are loaded into convoys with armed guards and driven north along thousands of kilometers of winding roads and desert tracks to Libya and Algeria, and as far east as Sudan.

Smuggling has long been a part of life in the vast and largely empty Sahel region, where armed insurgents claim a patchwork of ever-shifting territories. Jihadist movements linked to al-Qaida and IS, Tuareg separatist forces, and local ethnic militias take turns controlling roads and checkpoints along the way.

Moving illegal tobacco is a difficult and dangerous job, with trips taking between three and 10 days. Many truckers are killed by military or armed groups along the way. But it is well-paid: In a country where most people live on less than $1.90 per day, drivers can expect to earn between 6,000 to 10,000 euros for moving a load of contraband cigarettes.

It is also a lucrative trade for the drug lords and corrupt local officials in Mali’s restive northern regions.

Hama Ag Sid Ahmed, spokesman for the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA), an armed Tuareg independence movement that has controlled much of northern Mali on and off, said state officials and organized crime work together to profit from smuggling.

“Certain military officers, members of the intelligence services, heads of military zones in the northern regions are approached by drug lords,” he said.

“Large sums of money are paid for a contract related to a service rendered or to be rendered.”

A former tobacco industry insider said various militant groups, from the Tuareg separatists who have been fighting the Malian state for decades to the more recent offshoots of IS jihadists, also take a cut along the way.

“Product is escorted north by the Malian army or the gendarmerie [police], to protect it from so-called bandits,” said the former official, who would only speak on condition of anonymity due to safety concerns. “It would be given to the Tuareg for the trip onwards near Timbuktu, and then the Tuareg looked after paying IS in the Sahel.”

With the continuing violence and lawlessness, Malian customs have abandoned much of the north. Samba Ousmane Touré, an ex-employee of BAT’s distributor in Mali who is now a member of the country’s tobacco control committee, said armed groups have become the gatekeepers of the smuggling routes towards Algeria, Libya, and Niger.

“Armed groups play the role of customs,” he told OCCRP. “Yes, [BAT] knows.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_tta_accordion style=”modern” shape=”square” color=”chino” active_section=”1″ collapsible_all=”true”][vc_tta_section title=”Mr. Marlboro” tab_id=”1614947911857-561e7045-3ba3″][vc_column_text]One of the most high-profile jihadists in northern Mali, an al-Qaida operative known as Mr. Marlboro, is thought to have financed his jihad by smuggling cigarettes.

The one-eyed Mokhtar Belmokhtar allegedly orchestrated terror attacks, including one in Algeria in January 2013 that killed more than 35 people. He led the so-called Those Who Sign in Blood Battalion. In June 2013, U.S. authorities offered a reward of up to $5 million for information leading to Belmokhtar’s location.

His battalion had ties to key Malian armed groups, reportedly providing crucial military assistance to the terrorist group MUJAO against the MNLA during the battles of Gao and Timbuktu. A senior U.S. official said in July 2013 that Mr. Marlboro “has shown commitment to kidnapping and murdering Western diplomats and other civilians.” One such hostage was the former U.N. Niger envoy Robert Fowler.

Sid Ahmed, the spokesperson for the MNLA, said many terrorists like Belmokhtar started out trafficking cigarettes before moving onto harder substances, and then to violent jihad.

“The Arab drug barons created armed militias to protect their drugs and which later developed into the terrorist organizations that are present today in the Sahel region,” he said.

Research from The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime argues the long established smuggling networks in Mali and the Sahel evolved “first to move illicit cigarettes, later hashish and then, most profitably, cocaine.”

A 2017 KPMG report agrees, noting that the region’s cocaine trade overlays routes originally used to smuggle cigarettes, and that illicit trade “can also intersect with the operations of terrorist groups.”Illicit trade is “an important component of the local political economies” of Mali and other countries in the Maghreb, said the report, which was sponsored by Philip Morris, though it claims the trade is fueled by illicit cigarettes from free-trade zones in the United Arab Emirates.

Raoul Setrouk, who is pursuing a court case against BAT competitor Philip Morris in the state of New York for intellectual property theft, said that illicit tobacco in the region has consequences that go far beyond health and tax issues.

“I hope we don’t have to wait for a new Mr. ‘Marlboro’ like terrorist Mokhtar Belmokhtar to raise our consciousness,” he told OCCRP.[/vc_column_text][/vc_tta_section][/vc_tta_accordion][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Multiple sources, from soldiers and U.N. employees to businessmen, and armed militia members, told OCCRP that brands made by BAT and Philip Morris dominate the illicit trade.

Most common are Dunhills, produced in BAT’s factories in South Africa, and Philip Morris’ flagship brand Marlboros, which are handed to smugglers linked to armed groups by PMI’s politically connected representative in Burkina Faso, along with American Legends.

“Those which transit through are mainly three brands: Dunhill, American Legend and Marlboro,’’ said Hama from the MNLA. “It is the same thing also in northern Niger and not far also in the south of Algeria.”

Mohamed Ag Alhousseini, an independent researcher in the region, said much the same: “Even in Algeria, the trafficking is encouraged by the need of Marlboro and Dunhills, because they have other brands in the country.”

It’s hard to determine exactly how many illicit cigarettes are smuggled through Mali.

Trade data, information from customs officials, leaked BAT documents, and industry experts indicate there may be up to 4.7 billion surplus cigarettes in Mali every year — the equivalent of around 470 shipping containers of extra cigarettes. Some of them are produced in the country, but more are imported, almost all of them from South Africa.

Mali’s government has ignored years of blatantly false tax figures from Imperial Brands, a shareholder of the state tobacco company that distributes Dunhills in militant-run areas.

It’s also tricky to determine how much profit BAT makes because the company doesn’t separate out country figures in its annual reports. A company presentation from around 2007 estimates BAT’s market value in 18 “operational markets” in West Africa at 201 million British pounds (about US$394 million), and its market share in Mali at 61 percent. Another document, from 2012, gives gross turnover for Mali of 52.06 million British pounds ($84.6 million).

A BAT source, by contrast, estimated the company had a gross turnover of over $160 million in Mali in 2019 alone.

Imperial said SONATAM’s sales are “commensurate with the legitimate demand of the Malian population” and the company operates a stringent sales monitoring system.

“All cigarettes imported by SONATAM into Mali are done so legally under synallagmatic contracts with other commercial operators,” the company said in a statement.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_tta_accordion style=”modern” shape=”square” color=”chino” active_section=”1″ collapsible_all=”true”][vc_tta_section title=”Calculating the Oversupply” tab_id=”1614948109668-b60c3df1-e6f5″][vc_column_text]Understanding Mali’s illicit cigarette trade is a messy business — and that includes the data behind it. Because the illicit market is so opaque, many of the calculations rely on educated guesswork.

Euromonitor International, a strategic market research company, estimated the country’s retail volume at 3 billion cigarettes in 2016, rising to nearly 3.2 billion in 2020.

Leaked documents obtained by the University of Bath and shared with OCCRP show that in 2007, BAT estimated the country had demand for 1.9 billion cigarettes. In 2011, the company upped the estimate to 2.4 billion. Both these figures are lower than independent projections for the same years.

After northern Mali became a war zone, however, BAT’s calculations changed, with documents from 2013, 2014, 2015, and 2017 estimating the market as significantly larger than Euromonitor’s figures, at between 3 to 3.8 billion sticks.

The reason behind these high figures is unclear, as the same documents contain estimates of Mali’s smoking prevalence that are below the WHO’s. Experts have varying estimates for smoking rates. In 2011 BAT pegged it at 9.5 percent. The World Health Organization, by contrast, says 12 percent smoked in 2017, a rate that has remained steady over the past decade.

Yet data shows that every year since 2016, the first year after Mali’s 2012 rebellion for which trade figures are available there may have been up to almost 8 billion cigarettes in Mali.

Exact figures are hard to determine. A Malian customs official estimated an annual total of 4.6 billion cigarettes based on adding imports (2.6 billion in 2018 and in 2019 each year) with local production (around 2 billion in 2018 and in 2019 each year).

U.N. Comtrade data, however, shows between an estimated 3.4 billion to 5.9 billion cigarettes were exported to Mali per year from 2016 to 2019, nearly all of them from BAT’s regional hub, South Africa. Adding in local production, that could mean as many as 7.9 billion cigarettes are available in Mali each year.

Officials in Mali and South Africa confirmed the accuracy of the Comtrade numbers, which closely match regular reports on the value of tobacco imports released by the Malian government.[/vc_column_text][/vc_tta_section][/vc_tta_accordion][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Hallmarks of an Illicit Trade

In Gao, a city in northern Mali that has long been under the control of armed groups, a warehouse that distributes BAT’s cigarettes does a brisk trade.

Ahmoudou Ag Attiane, a local automotive dealer, told OCCRP that 20-ton tractor-trailers stocked with cigarettes commonly arrive at the warehouse. Many of the cartons are then trucked 10 hours north to Kidal, which is controlled by al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM).

“The law is the [AQIM group] that has the most power — the terrorists, the jihadists — and they banned smoking and also alcohol. So you see, someone can’t show off too much by opening up a place where everyone knows this is where cigarettes are stored, this is where cigarettes are sold.

“All these big traders have relations with the big boss of Kidal,” he said, “which means that they are protected.”

Sid Ahmed, the MNLA spokesperson, added to this point, saying: “The traffickers make a large order with a merchant in Gao or Timbuktu. The traders transport from Bamako to Gao and or Timbuktu. From Gao it goes to Algeria [and] Libya and from Timbuktu it goes to Mauritania and Algeria.”

The company that runs the warehouse, SONATAM — the state tobacco company whose shareholders include Imperial and the Libyan Arab African Investment Company — has been BAT’s distributor in Mali for years. Many of the cigarettes that pass through its warehouse in Gao are Dunhills from BAT’s plant in Heidelberg, near Johannesburg, which have accounted for up to 37 percent of South Africa’s total cigarette exports in recent years.

Unlike locally produced brands, the South African Dunhills come in packaging covered with health warnings in a major European language, French, known in the industry as a “clean label,” meaning they can be sold on the gray market.

David Reynolds, who built Japan Tobacco International’s program on countering the illicit tobacco trade, said BAT in South Africa is “notorious” for oversupplying the region.

“The rule is always the same: Oversupply plus lack of local controls leads to gray trade. That’s been a big part of BAT’s — and other cigarettes companies’ — business model for years,” he said.

“If you combine a major, high-end international brand, plus oversupply in a marginal market, such as Mali, with a clean label, you have all the hallmarks of intentional diversion into the parallel [illicit] trade.”

Documents obtained by OCCRP shed further light on how BAT’s Dunhills fall into the hands of armed groups in northern Mali.

A document from 2013 show SONATAM distributes between 25 percent to 75 percent of the three brands of BAT’s cigarettes sold in Mali. Three of its warehouses and distribution points are in rebel-controlled areas, including Gao, as well as Timbuktu and Mopti in the north of the country.

One BAT presentation from 2013 calls northern Mali a “war zone,” but notes that BAT has nonetheless identified future stockists and networks in Gao, Timbuktu, and Kidal. Another from 2017 highlights the “extremist insurgency” in eight of Mali’s regions, noting that three of them “remain completely dangerous to operate within owing to terrorist activities.”

However, an internal strategy memo from 2015 shows BAT planned to increase its business in these regions. The plan, called “Desert Storm” in an apparent reference to the U.S.-led military operation during the Gulf War, discusses how to reach “full potential” for their brands in Mali by incentivizing SONATAM to meet sales targets in areas including insurgency-run regions.

“As we know, in a dark market, the war is won on the battlefield with no pity for our competitors,” said the memo.

A 2007 presentation echoes the language of Europe’s colonial-era Scramble for Africa to describe the contest for the “crown jewels” of Mali and Ghana, casting West Africa as a battleground and speaking of “fighting ITG [Imperial Tobacco Group] to the death” and a “PMI [Philip Morris International] attack.”

“Mali was such an important market that BAT undertook a two-pronged strategy,” said Andy Rowell, a University of Bath researcher working with anti-tobacco watchdog STOP.

“The company set out to secure a ‘license to operate’ by schmoozing government officials. At the same time, the company sought to ‘delay and disrupt’ the operations of the opposition.”

Other BAT documents lay out its strategy to increase its market share against lower-cost cigarettes in Bamako and “UPC” — jargon for “Up Country” — including detailed analysis of the competition. They also show the company’s fine-grained ability to map and track contraband in West Africa: One presentation from around 2006 lists BAT’s “informants” in Mali and Niger.

Telita Snyckers, a lawyer who previously held senior positions at the South African Revenue Service and author of the book Dirty Tobacco: Spies, Lies and Mega-Profits, called the operation “corporate espionage stuff.”

The slides of the 2007 presentation discuss BAT’s strategy for West Africa, including Mali, stressing the need to “Grow VFM in Freedom Markets and Mali.” Snyckers said that VFM, or “Value For Money,” is a euphemism for smuggling and illicit channels.

In another presentation from 2009, a group of legal and security officials from BAT was told that “Mali, as the principal market which has the highest volume of illicit trade, is where we have the most to gain by increasing contestable market space.”

A BAT spokesperson declined to comment on the documents without seeing them before the publication of this article, but added, “we are not aware of the phrases ‘dark market’ or ‘value for money brands’ relating to illicit trade.”

Extraordinary Mistakes or Barefaced Lies

The rampant tobacco smuggling in Mali isn’t only down to the cigarette companies. OCCRP’s reporting indicates there is little state oversight of the industry.

For one thing, the government has overlooked blatant inaccuracies in figures from BAT’s distribution partner, Imperial, which for two consecutive years stated in its public accounts that SONATAM paid 5.5 million euros in taxes more every year than its total turnover.

West African financial analyst Oumar Ndiaye called the numbers “impossible.” Some former tobacco executives in Mali dismissed the SONATAM turnover figures as deliberate lies to fiscal authorities.

Imperial attributed them to an error in currency conversion, with West African CFA francs mistakenly not converted into euros. The company declined to provide documentation, however, and referred reporters to the Malian government, which did not respond to several requests for comment.

Alex Cobham, the chief executive officer of the Tax Justice Network and an expert on tax avoidance by multinationals, said Imperial’s explanation “doesn’t stand up,” and that repeating the same numbers over multiple years is “implausible.”

“Whoever wrote these numbers down thought nobody would ever look at them,” he said. “They’re either making extraordinary mistakes, year after year, or they’re telling you barefaced lies, or both.”

He also faulted the company’s auditor, PricewaterhouseCoopers, for apparently accepting the shoddy accounting.

“The idea that one of the world’s leading accounting firms, that prides itself on the auditing of multinationals to ensure they’re behaving as they should do, would not have picked up any of this in their rigorous annual audit process is difficult to square with any claim that corporate tax is being paid or audited on an appropriate basis,” he said.

It’s unclear who put together the “impossible” numbers.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_tta_accordion style=”modern” shape=”square” color=”chino” active_section=”1″ collapsible_all=”true”][vc_tta_section title=”Imperial’s History in West Africa” tab_id=”1614948437767-f15da48b-35eb”][vc_column_text]Imperial inherited much of West Africa’s tobacco business from Bolloré Group, a giant in France’s former colonies which operates a number of ports across Africa and logistics companies worldwide.

The tobacco purchase bought Imperial a stack of elite connections. The directors of SITAB, an Imperial subsidiary in Ivory Coast, included a relative of former President Felix Houphouet-Boigny. Lassine Diawara, the chairman of the board of directors of MABUCIG, a Burkina’ cigarette manufacturer. His online biography says he is a Knight of the National Order of Merit in France. He has traveled with Blaise Compaoré, the ex-president of Burkina Faso. SONATAM was run for a number of years by Cissé Mariam Kaïdama Sidibé, who became prime minister of Mali for a short period in 2011.[/vc_column_text][/vc_tta_section][/vc_tta_accordion][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Ross Delston, a U.S.-based lawyer and anti-money laundering compliance expert who has worked in West Africa, said the Malian government could well have an incentive to overlook years of obvious errors.

“Any governmental authority that has a monopoly over a given commodity also has a high degree of risk for corruption,’’ he said after discussing SONATAM figures with OCCRP. “It’s just too easy to skim off a bit, or more than a bit, for the people at the top.”

Touré, the ex-employee of BAT’s agent in Mali, agreed, saying that the state shared in the responsibility for the bad accounts, adding, “I think that [in] corrupt states like ours, the tobacco industry has a lot of power over their leaders.”

Mali’s government declined to comment.

U.N. trade figures also indicate years of discrepancies equaling millions of dollars in the price of the country’s cigarette imports.

Mali imported more than 3 million kilograms of cigarettes from South Africa annually in both 2016 and 2017, representing around 95 percent of the country’s cigarette imports. An ex-BAT official said that the only cigarettes Mali imports from South Africa are BAT’s Dunhill cigarettes, a point confirmed in an earlier BAT document.

If the former employee is correct, BAT reported to the government of South Africa it sold the cigarettes for under $7 per kilogram, while SONATAM reported it bought the cigarettes for $15 per kilogram in 2016 and 2017, the years for which U.N. trade data is available for Mali. The discrepancy amounts to between $29.1 million and $32.8 million per year, and appears to have continued afterward, according to Malian government data available for 2018.

It’s unclear exactly what is behind the difference.

A Malian customs official dismissed the numbers as a likely lag in reporting shipments.

Two former tobacco industry insiders told OCCRP that trade mis-invoicing, a method for moving money across borders that involves deliberate falsification of the volume or price of goods, is common practice in the company’s dealings with Mali.

“Mis-invoicing, under- and over-invoicing, and invoicing direct to the U.K. instead of in the delivered country were all used at one time or another,” one of them said.

Cobham, of the Tax Justice Network, said SONATAM’s overpayment is “very much consistent with the longstanding history of commodity trade price manipulation for profit-shifting purposes.”

That’s apparently not unusual for BAT. In 2019, Cobham’s organization authored a report that found BAT used various methods to shift profits out of poorer countries, at a scale that could deprive eight countries in Asia, Africa, and South America of nearly US$700 million in tax revenue until 2030.

“The bottom line is BAT is manipulating the price of the same commodity and the transaction in a way that can’t be justified by any possible transport costs, and any auditor worth their salt should have picked that up,” he said.

SONATAM did not respond to requests for comment.

Imperial did not respond to several OCCRP requests for clarification, saying only that the company “is committed to high standards of corporate governance” and “totally opposed to smuggling which benefits no one but the criminals involved.”

A BAT spokesperson said the prices of its tobacco “are in line with what external, independent parties would charge,” which is documented in the company’s tax strategy.

“BAT entities … comply with all applicable tax legislation and regulations in the countries where we operate,” he said.

PricewaterhouseCoopers and its French partner Xavier Belet, who audits the SONATAM accounts, ignored several requests for comment by OCCRP.

Friends on the Ground

From warehouses in Gao, Timbuktu, and Mopti, Dunhills flow north largely unchecked by Malian regulators.

“With the insecurity, the customs abandoned an important part of the north because of the narco-traffickers,” said Aboubacar Sidiki Kone, a Malian customs official.

Even if customs did man Mali’s lonely desert posts in the north, it’s unclear what they would do. An internal document obtained by OCCRP shows Malian customs and police were sponsored by BAT.

In a 2013 presentation, BAT lays out an “action plan” for a series of scheduled raids to be carried out by Malian customs and police in collaboration with company agents, tallying seizures of illicit cigarettes made by its competitors. A mission order and a protocol agreement in the presentation show BAT was supposed to pay for these raids.

Internal documents show BAT used informants in West Africa to keep abreast of the illicit trade.

A former BAT employee described staffers in Mali feeding intelligence on contraband to customs agents, helping them to seize the brands of other manufacturers.

Sory Coulibaly, a former sales executive for a BAT distributor in Mali, added that BAT has sweetened the deal, equipping customs agents and police with motorcycles and small patrol boats. Touré added that BAT has given customs several new cars every year.

The cooperation between Mali’s customs and BAT was formalized further in 2019, when local media reported Malian customs’ announcement of a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with the tobacco company.

Deals with customs agencies are a longtime tobacco industry strategy, detailed in a paper published by the BMJ’s journal Tobacco Control the same year. Eric Crobie, Stella Bialous, and Stanton A. Glantz found that there are more than 100 such MoUs around the world, that they violate the World Health Organization’s international tobacco control treaties, and are ineffective at reducing smuggling.

Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) were seen by transnational tobacco companies as “useful to provide access to decision makers and promote the image of [tobacco companies] as government partners,” the authors wrote.

In Mali’s case, the details of neither its deal with BAT nor an MoU it signed with SONATAM are easy to find. Abdel Kader Sangho, director of the customs’ training center, ignored several inquiries from reporters.

Touré, the Malian tobacco control expert, said the country’s tobacco laws are weak and there is little enforcement of them on the ground. “Our anti-smoking texts are not strong and most of our leaders are corrupt,” Touré said. “The texts exist, but it remains to apply them in the field.”

Today, SONATAM’s statistics claim Mali’s contraband levels are at an all-time low, while BAT continues to flood the country with cigarettes far exceeding demand.

Anecdotal evidence suggests the flows of smuggled tobacco may even be increasing. Touré said he has observed that the amount of Dunhills moving to the north, have recently been on the rise.

“I’m sure these cigarettes are destined for other countries, Niger, Algeria and others,” he said.

Meanwhile BAT and the Malian government are planning to make more cigarettes in the country. In 2017 they partnered up to build a new $18.2 million factory, according to local media reports. It is expected to open this year with the capacity to produce 3 billion Dunhills per annum.

–

Sandrine Gagne-Acoulon contributed reporting.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]