The New York Times praises the US-American NGO GiveDirectly (GD), a GiveWell top charity, for offering a ‘glimpse into the future of not working’ and journalists from the UK to Kenya discuss GD’s unconditional cash transfer program as a revolutionary alternative in the field of development aid. German podcasts as well as international bestsellers such as Rutger Bregman’s Utopia for Realists portray grateful beneficiaries whose lives have truly changed for the better since they received GD’s unconditional cash and started to invest it like the business people they were always meant to be. At first glance, GD indeed has an impressive CV.

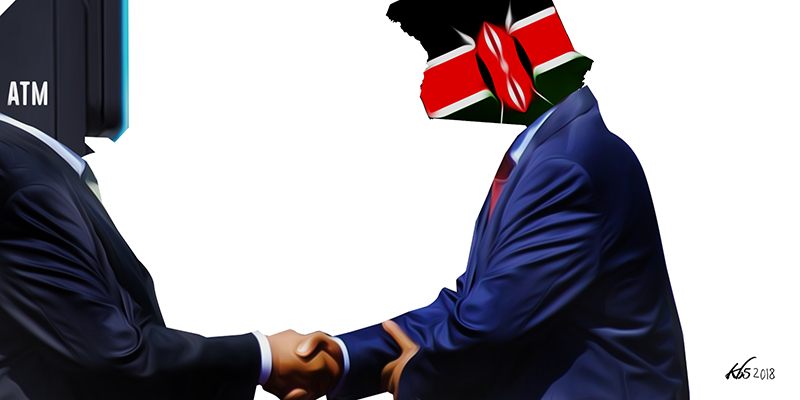

Since 2009, the NGO has distributed over US$160 million of unconditional cash transfers to over tens of thousands of poor people in Kenya, Rwanda, Uganda, the USA and Liberia in an allegedly unbureaucratic, corrupt-free and transparent way. Recipients are ‘sensitized’ in communal meetings (baraza), the cash transfers are evaluated by teams of internationally renowned behavioral economists conducting rigorous randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and the money arrives in the recipients’ mobile money wallets such as the ones from Mpesa, Kenya’s celebrated FinTech miracle, without passing through the hands of local politicians.

In 2015 and after finalizing a pilot program in the Western Kenyan constituency Rarieda (Siaya County), GD decided to penetrate my ethnographic field site, Homa Bay County. On the one hand, they thereby hoped to enlarge their pool of potential beneficiaries. On the other hand, they had planned to conduct further large-scale RCTs (one RCT implemented in the area, studied the effects of motivational videos on recipients’ spending behavior). To the surprise of GD, almost 50% of the households considered eligible for the program in Homa Bay County refused to participate. As a result, the household heads waived GD’s cash transfer which would have consisted of three transfers amounting to a total of 110,000 Kenyan Shillings (roughly US$1,000).

In order to understand what had happened in Homa Bay County and why so many households had refused to participate, I teamed up with Samson Okech, a former field officer of Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA) who had conducted surveys for GD in Siaya. Samson had been an IPA employee for over ten years and belongs to the extended family I work with most closely during fieldwork. During our long qualitative interviews with recipients of GD’s cash transfer and former field officers as well as Western Kenyans who refused to be enrolled in the program, the celebratory reports by journalists and scholars were replaced by a bleaker picture of an intervention riddled with misunderstandings and problems.

Before I offer a glimpse into what happened on the ground, I want to emphasize that I am neither politically nor economically against unconditional cash transfers which, without a doubt, have helped many individuals in Western Kenya and elsewhere. It is not the what, but the how against which I direct my critique. The following two sections illustrate that a substantial part of Homa Bay County’s population did not consider GD’s intervention as a one-time affair between themselves and GD. In contrast, they interpreted GD’s program either as an invitation into a long-term relationship of patronage or as a one-time transfer with obscured actors.

These interpretations should make us aware of ethical problems entailed in conducting social experiments (see Kvangraven’s piece on Impoverished Economics, Chelwa’s and Muller’s The Poverty of Poor Economics or Ouma’s reflection upon GD’s randomisation process in Western Kenya). They can also crucially encourage us to think about ways of radically reconfiguring the political economy of development aid in Africa and elsewhere.

Instead of framing relations between the West and the Rest as relations between charitable donors and obedient recipients, in my conclusion I propose to ‘ungift’ unconditional cash transfers as well as development aid as a whole. Taking inspiration from rumors claiming that Barack Obama, whose father came from Western Kenya, has created GD in order to rectify historical injustices, I suggest rethinking cash transfers as reparations or debts repaid. Consequently, recipients should no longer be used as ‘guinea pigs’ but appreciated as equal partners and autonomous subjects entitled to reap a substantial portion of the value produced in a global capitalist economy that, historically as well as structurally, depends on exploiting them.

Why money needs to be spent on ‘visible things’

Those were guidelines on how to use the money. It was important that what you did with the money was visible and could be evaluated’, William Owino explained to us after we had asked him about a ‘brochure’ several other respondents had mentioned. One of the studies on the impact of GD’s activities in Siaya also mentions these brochures. In order to ‘emphasize the unconditional nature of the transfer, households were provided with a brochure that listed a large number of potential uses of the transfer.’

When being asked which type of photographs and suggestions were included in these brochures, respondents mentioned photographs of newly constructed houses with iron sheets, clothes, food and other gik manenore (‘visible things’). When we inquired further if the depicted uses included drinking alcohol, betting, dancing or other morally ambiguous goods and services, the majority of our respondents dismissed that question by laughing or by adding that field officers had also advised them against using the money for other morally dubious services such as paying prostitutes or bride wealth for a second or third wife.

One of our respondents in Homa Bay took the issue of gik manenore to its extreme by expressing the opinion that GD’s money must be used to build a house with a fixed amount of iron sheets and according to a preassigned architectural plan so that GD, in their evaluation, would be able to identify the houses whose owners had benefited from their program quickly and without much effort. Such practices of ‘anticipatory obedience’ are also implicitly at work in the rationalizations of another respondent. He expected that GD’s field officers who had asked him questions about what he intended to do with the money during the initial survey – questions whose answers had, in his opinion, qualified him to receive the cash transfer – would one day return to see if he had really used the money according to his initially stated intention. The logic employed is clear: The ‘unconditional’ cash transfers needed to be spent on useful and, if possible, visible and countable things so that GD would return with further funds after a positive evaluation.

Recipients understood the relation with GD not as a one-off affair, but as an entrance into a long-term relation of fruitful dependency. In contrast to GD which, like most neoliberal capitalists, understands unconditional cash as a context-independent techno-fix, the inhabitants of Homa Bay framed money as an entity embedded in and crystallizing social power relations.

From such a perspective, free money is not really free, but like Marcel Mauss’ famous gifts, an invitation into a ‘contract by trial’ which has the potential to turn into a long-term relationship benefitting both partners if recipients pass the test and reciprocate with obedience. While some actors framed the offer of unconditional cash as a test that could lead into an ongoing patron-client relationship between charitable donors and obedient recipients, others, the majority who refused to accept GD’s offer, interpreted it as a direct exchange relation with unseen actors.

Why money is never free

‘People in the market and those I met going home told me it is blood money’, Mary, a 40-year old mother remembered. After she had been sampled, Mary had never received money from GD but failed to understand why and believed the village elder had ‘eaten’ her money. She further told us that rumors about ‘blood money’ circulated in church services and funeral festivities. ‘Blood money’ refers to widespread beliefs that accepting GD’s cash implied entering into a debt relation with unknown actors such as a local group sacrificing children or the devil.

Comparable rumors playing with the well-known anthropological trope of money’s (anti)-reproductive potential circulate widely in Homa Bay: Husbands who wake up only to see their wives squatting in a corner of the room laying eggs, a huge snake that lives in Lake Victoria and vomits out all the money GD uses, mobile phones that can be charged under the armpit or find their way into the recipient’s bed if lost or thrown away (many people allegedly threw their phones away in order to cut the link to GD), money that replenishes automatically or a devilish cult of Norwegians that abducts Kenyan babies and transports them to Scandinavia where they are adopted into infertile marriages.

All of these rumors, which are epitomized in a phrase some recipients considered to be GD’s slogan, Idak maber, to idak matin – (‘You live well, but you live short’) – revolve around the same paradox: Money initially offered with no strings attached, but whose reproductive potential will soon demand blood sacrifice or lead to a fundamental change in one’s own reproductive capacities.

Local attempts to ‘conditionalize’ GD’s unconditional cash as well as rumors about tit-for-tat exchanges with the devil undermine GD’s assumption that their cash transfers are perceived by recipients as unconditional. This has two consequences. On the one hand, it questions the validity of studies trying to prove that the program was successful as an unconditional cash transfer program. On the other hand, it urges us to focus on the unintended consequences caused by GD’s intervention. While Western Kenyans who have given consent to participate in the intervention invested their hopes in an ongoing charitable relation with GD, those who have refused to participate – as well as some who did – have been haunted by fear and anxiety triggered by situating GD’s activities in a hidden sphere.

All this raises ethical and political questions about GD’s intervention in Homa Bay County. Did GD, an actor that is neither democratically elected nor constitutionally backed up, have the right to intervene in an area where almost 50 % of the population refused to participate? Did the program really reach the poorest members of society if accepting the offer depended on understanding the complex networks of NGOs that constitute the aid landscape? Should it not be considered problematic that a US-American NGO uses whole counties of an independent country as laboratories where they experimentally test the feasibility of unconditional cash transfers in order to assure their donors that recipients of unconditional cash ‘really’ do not spend donations on alcohol and prostitutes?

Apart from raising these and other ethical and political questions, the reactions of the inhabitants of Homa Bay County can be understood as mirrors reflecting a distorted but illuminating image of the development aid sector. Narratives about women laying eggs and satanic cults sacrificing children exemplify an awareness of the fact that, on a structural level, the development aid sector is shot through with inequalities and obscure hierarchical power relations between donating and receiving actors. At the same time, recipients’ anticipatory obedience to use the cash on ‘visible things’ unmasks a system that appears overwhelmed by the necessity to constantly evaluate projects in order to secure further funding.

By ‘conditionalizing’ cash transfers as long-term patronage relations or tit-for-tat exchanges with the devil, inhabitants of Homa Bay unmask GD’s ‘myth of unconditionality’ and thereby relocate GD into the wider development aid world in which they have never been equal partners.

Why we must ‘ungift’ development aid

‘I think it was because of Obama’, a former colleague of Samson who had administered the surveys of GD in Siaya County told me while we enjoyed a meal in a restaurant along Nairobi’s Moi Avenue after I had asked him why the rejection rates of GD’s program in Siaya had been so low. According to rumors that circulated widely during GD’s first years in Siaya, Barack Obama, whose father came from a village in Siaya County, had teamed up with Raila Odinga, an almost mythical Luo politician, in order to channel US-American funds ‘directly’ to Western Kenya, i.e. without passing through the Central Kenyan political elite who had – in 2007 as well as 2013 – ‘stolen’ the elections from Raila.

As a consequence, at least some recipients did not agree with interpretations of the cash transfers as market exchanges with shadowy actors or invitations into long-term relationships of patronage. Rather, they conceptualized the transfers as reparations originating in Obama’s attempt to recoup losses accumulated by the Luo community due to political injustices provoked by the actions of what many consider to be a corrupt Kikuyu elite. This conjuring of a primordial ethnic alliance between Obama and Western Kenyans might strike many as chimerical.

Be that as it may, we should acknowledge that the rumor of Obama’s intervention situates the cash transfers in a social relation between two equals who accept their mutual indebtedness and act accordingly by putting things straight. By reinterpreting GD as a clandestine operation invented by their political leaders, Barack Obama and Raila Odinga, inhabitants of Siaya portray themselves as belonging to a community of interdependent equals whose members are entitled to what the anthropologist James Ferguson has called their ‘rightful share’.

How would development aid look like if we dared to transfer this idea of a community whose members acknowledge their equality and mutual indebtedness to our global economic system? One way to redeem the fact that we all live in a highly connected capitalist economic system spanning the whole globe and depending on exploiting a huge portion of the global community would be to follow in the footsteps of the inhabitants of Siaya and rebrand cash transfers as reparations being paid for historical and structural injustices.

By way of conclusion, I want to suggest the idea of ‘ungifting’ development aid, i.e. to reframe it as a duty and to accept that recipients of cash transfers have the right to receive their share of the value produced by the global capitalist economic system. Consequently, cash transfers should be considered as debts repaid and not as gifts offered.

–

Names of individuals in this article have been anonymized.

This article was first published in the Review of African Political Economy.

Names of individuals in this article have been anonymized.