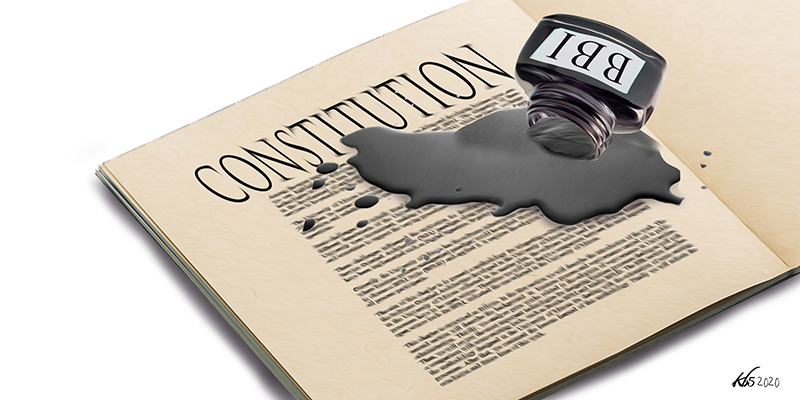

When the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI) was launched and the promise made that we would soon have significant constitutional changes, I doubted that we would achieve any constitutional changes before 2022 – a critical timeline because of the general elections in August that year. I also doubted whether those who were rushing to speak about the imminent changes to the constitution had full appreciation of what it would really take to effect amendments to the 2010 constitution. Yet, some critical voices supporting the BBI even gave timelines of early to mid-2019 when Kenyans should expect the amendments to be in place.

Two years ago, I had both legal and political reasons to doubt why constitutional changes through the BBI process were an implausible improbability. I still hold most of those views but with the benefit of evidence, unlike two years back when my views were based mostly on logical deduction of what the constitution provides and anticipates on constitutional changes.

However, before I get into the reasons why constitutional changes before 2022 are highly improbable, a critical word about the nature of our constitution.

A people’s transformative constitution

The 2010 constitution is transformative. This nomenclature is critical. The constitution sought to overhaul instead of build on the past. The past was, in totality, undesirable and unsustainable. The constitution itself – and the process that brought it into being – contains many explicit and specific markers evincing its transformative nature.

First on process.

The 2010 constitution was drafted through a very participatory process. Critically, and as Yash Ghai argues, the 2010 constitution was the constitution the people imposed on the political elite. The level of participation facilitated by civil society and the Constitution of Kenya Review Commission (CKRC) and later the Committee of Experts (COE) was deliberate to ensure that significant content of the constitution derived from what the people wanted. In fact, desperate, last-minute attempts by Members of Parliament (MPs) to dilute the draft constitution through a raft of amendment proposals in Parliament failed, thanks to the ingenuity of the Constitution of Kenya Review Act 2018, which contained time-bound self-executing provisions to forestall any attempt at political subterfuge.

The 2010 constitution was drafted through a very participatory process. Critically, and as Yash Ghai argues, the 2010 constitution was the constitution the people imposed on the political elite.

The architecture of the constitution is additional evidence of its transformative nature. The constitution opens by underscoring the sovereignty of the people and the supremacy of the constitution, followed by national values and principles of governance, and then with a detailed and elaborate Bill of Rights. Unlike the former constitution, institutions of governance only feature in the middle part of the constitution – and not before it details, in Chapter Six, the integrity principles that regulate leadership. This is unlike the former 1969 constitution whose chapter arrangements consciously signalled a hierarchical president-centred state with the chapter on the presidency featuring very early on in the constitution in Chapter Two. In contrast, in the 2010 constitution, the executive is tucked away in Chapter Nine.

Additionally, the length and language of the 2010 constitution lends significant credibility to its mission of transformation. On length, the constitution is overly detailed, which signals a trust issue that Kenyans had, especially with lawmakers and the executive. The details were to ensure that lawmakers did not have much discretion to legislate on issues considered critical by the people (a sign of past constitutional trauma), given that under the former constitution lawmakers had, under the thumb of presidential patronage, been overly enthusiastic to amend the constitution and legislate on infinite retrogressive laws. On language, the constitution was drafted in the most plain and accessible English to dispel the past practice of making a constitution a document that is accessible mainly to lawyers and other elites in society. This accessibility creates a greater sense of ownership of the constitution by the people.

On implementation, the constitution attempted to insulate itself from executive manipulation by establishing and by extensively spelling out the institutions and rules of its implementation. To illustrate, the constitution created many independent bodies and commissions responsible for monitoring and enforcing implementation of varying aspects and granted courts extensive powers to adjudicate and enforce all constitutional aspects on any individual. While the executive may have now found a way to patronise most of those institutions through unmeritorious appointments, the institutions’ constitutional stature and powers still remain intact.

Finally, and critically, the content. There is a lot to discuss here, but I want to list four key features in the content of the constitution that points to its transformative nature: the centrality of the people; the ubiquity of values and principles of governance in every chapter of the constitution; the emphasis on the rule of law vis-à-vis the powers of the judiciary; and a very elaborate and onerous amendment procedure.

Now, let me go back to what I set out to discuss: the improbability of constitutional amendments through the BBI process.

The time and constitutional tethers on BBI

There are at least three fundamental reasons why constitutional amendments before 2022 are an improbability. First, our constitution provides a complex and onerous amendment procedure for any consequential amendment. Second, and because of this complex and onerous amendment procedure, for any amendment to succeed, a broad and genuine political consensus is required. The third reason is more technical and relates to the fact that our constitution explicitly creates checks against unconstitutional constitutional amendments, including those that affect the basic structure of the constitution.

Let me try to elaborate a bit more on each of these.

A complex and onerous amendment procedure

Articles 255 to 257 expressly stipulate the procedures necessary to effect constitutional amendments. Three possibilities are contemplated:

- The first amendment process is a simple one that only involves Parliament. This process, provided for under Article 256, allows for constitutional amendments through parliamentary approval. This procedure is reserved for minor, non-structural and mostly non-controversial amendments. However, even though the least demanding procedurally, the process is still quite elaborate. For example, it requires significant public participation, including ensuring that there is a three-month public consultation period between the time a constitutional amendment bill is tabled in the National Assembly or the Senate and its debate and consideration. Additionally, for a constitutional amendment to succeed, it must be supported by two-third members of each House of Parliament– a critical number that requires significant parliamentary mobilisation.

- The second amendment process involves more controversial amendments that touch on a subject that requires both the passage of amendments by Parliament through two-thirds support and a referendum. As I will discuss later, there are imponderable number of amendments that require passage through a referendum.

- The third amendment process through a popular initiative is the most onerous. The first step requires the sponsor of the amendment to collect, and have the Independent Electoral Boundaries Commission (IEBC) to verify that at least one million registered voters support the amendment. Once verified, the Bill is sent to the County Assemblies with a requirement that more than half of them approve it for it to be eligible for consideration by Parliament. The Okoa Kenya Bill of 2016 sponsored by the Coalition for Reform and Democracy (CORD) with so much fanfare failed at this first step. Thirdway Alliance’s Punguza Mzigo Bill of 2019 failed at the second step when only one County Assembly supported it. An amendment bill through a popular initiative still requires consideration by Parliament and has to meet the procedural hurdles required of amendment bills going through the other two processes except for one exception – if Parliament fails to pass a popular initiative bill, then the bill is put to a vote in a referendum. Regardless, even when a popular initiative bill is passed by Parliament but deals with an issue stipulated to require a referendum, it must still be voted for in a referendum.

The mandatory time needed to effect a constitutional amendment is lengthy. The timeline for passing a non-controversial Parliament-only amendment is at least seven months from the date the bill is first tabled in Parliament. This is because, beside the usual administrative processes a bill has to go through, there is the extra requirement that each house must wait for at least ninety days between the first and second reading of a constitutional amendment bill in order to facilitate thorough public participation. In legislative politics, seven months is a lifetime. It is impossible for sponsors of the bill to guarantee, from the outset, that initial support or consensus they procured for an amendment would be sustained for that long. This has been the fate of endless constitutional amendment bills introduced in Parliament to amend the 2010 constitution.

The role of courts in amending the constitution

There is another factor that makes the amendment process even more onerous and time-consuming – the courts. Courts have the power to look at whether the sponsors of a constitutional amendment have complied with the necessary constitutional procedure for each relevant step.

While it is unlikely that courts would interfere with amendments that are before Parliament – by, for example issuing orders to stall the parliamentary process – still the uncertainty that litigation presents becomes a hiccup in the process. This was the lesson MPs learnt, and through the hard way, in 2013 when they introduced a constitutional amendment bill that sought to take them out of the designation of state officers. The MPs had mistakenly thought that the amendment would allow them to raise their salaries and perks unfettered by the Salaries and Remuneration Commission. The Commission for the Implementation of the Constitution sued, requesting the court to declare the proposed amendments unconstitutional. Although Justice Lenaola, who decided the matter, did not restrain Parliament from its efforts to amend the constitution, his judgment was clear that if Parliament passed a constitutional amendment through a process that was non-compliant with the constitution, the court would invalidate the amendment. After the judgment, Parliament quietly abandoned the amendment bill. I still return to the role of courts when I discuss unconstitutional constitutional amendments below.

There is another factor that makes the amendment process even more onerous and time-consuming – the courts. Courts have the power to look at whether the sponsors of a constitutional amendment have complied with the necessary constitutional procedure for each relevant step.

Broad support and genuine consensus

The complexity and onerous demands to enact constitutional amendments were tools that the drafters of the constitution used to ensure that any proposed constitutional amendments enjoyed broad and multi-partisan and multi-sectoral support. The lengthy timeline needed to successfully pass constitutional amendments underlines the need for broad and genuine civic and political consensus-building. Because constitutional changes are high-stake issues, sustaining civic and political support that is based either on intimidation or political convenience is mostly untenable. Essentially the type of proposals that can weather the onerous amendment procedures and lengthy amendment processing timelines would be of the nature that address a genuine, enduring and people-centric issue.

There is another reason why broad support and consensus that go beyond the political elites is necessary to achieve constitutional amendments. Article 255 spells out amendments that must be subjected to a referendum, including on critical and significant issues, such as the territory of Kenya, the independence of the judiciary and the Bill of Rights.

The complexity and onerous demands to enact constitutional amendments were tools that the drafters of the constitution used to ensure that any proposed constitutional amendments enjoyed broad and multi-partisan and multi-sectoral support.

The list in Article 255 may seem unexpansive, but in reality and substance, it is a very elastic and nearly imponderable list. Regardless, most of the critical provisions that politicians would be keen to amend (judging from the Okoa Kenya Bill and the initial BBI report) would demand a referendum. This is because the politicians’ proposals have always oscillated around amendments relating to the supremacy of the constitution, the sovereignty of the people, the nature of or term of the president, national values, the functions of Parliament, the independence of the judiciary or devolution, all of which are enumerated as requiring passage through a referendum. Thus the kind of changes that politicians wish for to be able to create a power-sharing matrix that allows as many of them to be on the trough at the same time call for a referendum.

A referendum not only adds to the timelines, but presents other complexities. These include the need for significant financial outlay to fund the referendum, as well as the high possibility of political volatility and unsettling political and economic paralysis triggered by the referendum campaigns. These factors should be consequential in determining how much push BBI should expect from the state – and Kenyans’ goodwill – especially given the financial disruption that COVID-19 has imposed on the economy.

Those wielding executive political or “handshake” power might easily haggle for support for the amendments from the political elites by, for example, doling out political positions and financial handouts or through political intimidation. Yet these tactics are likely to be ineffective in procuring voters’ acquiescence. To be sure, without the certainty that a critical mass of voters will readily support proposed amendments makes a push for constitutional amendments tentative, illogical, unwise, and a fragile political gamble.

Importantly, when such a gamble is being taken so close to a constitutionally-ordained general election date, it is likely an unworthy venture. That is likely to be the fate of BBI. Essentially, by the time (if) the process has fully matured for a referendum, it will likely be too close to August 2022, forcing Raila Odinga to choose between a campaign for the presidency or a campaign to change the constitution. I can bet what his choice will be – as I can easily bet that if he decides to straddle both, it will likely be the surest way to lose both the referendum and the presidency. And for Uhuru Kenyatta, overseeing a general election and a referendum close to each other will only be politically sensible if he wants to be prime minister – an obvious political minefield.

Unconstitutional constitutional amendments and the basic constitution structure doctrine

A much more technical and unpredictable issue poses additional significant risks to the anticipated BBI amendments. Again, going by the initial reports and credible political rhetoric, the changes proposed are likely to affect at least two critical areas: the system of governance to introduce either a parliamentary system or a fused presidential and parliamentary system; and changes to help neuter the judiciary because of its consistent fidelity to the 2010 constitution and for arrogating itself the guard rail role to push back against the executive’s push towards authoritarianism.

An additional possible change is on devolution, dangled as a carrot either to appease voters by increasing the minimum amount of funds constitutionally transferred to counties or as a strategy to buy off the support of governors by creating a third tier of government which the retiring governors will believe is theirs to superintend.

Certainly I could be off the mark with the above predictions, but the bottom line is that after so much hype, it is hard to see what consequential amendments BBI would propose that will not, in form or substance, at least significantly alter the system of governance under the 2010 constitution.

But first a clarification on what unconstitutional constitution amendments and basic structure doctrine entails. The notion of basic structure holds that a constitution, like a multi-storey building, has varying architectural features. Some of these features (chapters or provisions) could be removed or substituted without affecting the structural integrity of the building. But there are basic or fundamental features that cannot be removed or substituted without compromising a building’s foundational and structural integrity. In the constitution, the basic or fundamental features or provisions constitute the basic structure of the constitution. The rule then is that provisions or features that constitute the basic structure of the constitution are unamendable. The only way to replace them is by overhauling the entire constitution.

The concept of unconstitutional constitutional amendments is broader. It encompasses the aspect of the basic structure of the constitution – which tend to deal with substantive content of the constitution – as well as the processes the constitution provides for its amendment. Where the constitution requires a certain procedure to be followed in its amendment, the consequence of non-compliance with any aspect of the procedure results in an unconstitutional constitutional amendment. Both concepts are central in determining the constitutionality and validity of any amendments made to the Kenyan constitution. But let’s start with the basic structure doctrine.

Essentially, by the time (if) the process has fully matured for a referendum, it will likely be too close to August 2022, forcing Raila Odinga to choose between a campaign for the presidency or a campaign to change the constitution.

Already Kenyan courts have accepted that certain features of the constitution constitute its basic structure, including the national values and principles of governance. Importantly, the court in the case pitting MPs against the Salaries and Remuneration Commission was emphatic and precise that it would declare invalid any constitutional amendments that interfere with the basic structure of the constitution. Additionally, in that case, the court demonstrated that it would thoroughly interrogate any constitutional amendment to be sure that in no way does it affect the basic structure or interfere with the internal coherence of the constitution. This approach allows the court – as it should – significant leeway to invalidate constitutional amendments created for political convenience or which are just a patchwork to facilitate selfish ends.

The logic of intertwining the basic structure doctrine and the concept of unconstitutional constitutional amendments is readily available. The latter insists on the need for those sponsoring an amendment to the constitution to ensure that they strictly adhere to constitutional processes of amendments, including observing the relevant mandatory timelines, ensuring adequate and effective public participation, including observing a mandatory 90-day constitutional hiatus between the first and second reading of the bill, among other more technical procedural requirements. Failure to comply with any of the enumerated or derivative normative requirements exposes any constitutional amendment to the risk of being invalidated by the court.

The true fate of BBI

Critically, the concept of unconstitutional constitutional amendments and the confirmation that Kenya’s 2010 constitution contains a basic structure has one significant implication for BBI or any other substantial amendments that may be proposed. The implication is that any substantial amendments that Parliament forces through without the involvement of the people through a referendum will be invalid.

This means that the efforts that Uhuru Kenyatta and Raila Odinga are currently involved in of whipping parliamentarians into line through carrot-and-stick tactics in preparation of stifling parliamentary dissent against BBI amendments may all end in nought. The true fate of BBI amendments hinge on time and the people.