Release phase dynamics force ecological and human systems to adapt and evolve. The process inscribes a conflictive and often violent pathway as developments across Kenya’s rural landscape confirmed. The assault on the environment suggested that the right to life ranked low in the Kenya’s political elite’s hierarchy of needs. The eruption of violence across the Rift Valley confirmed this hypothesis.

Grievances over land and access to economic resources had been fermenting for several generations. The unrelenting encroachment presented an opportunity for Kanu hawks to curry favour within their marginalised minority communities. The escalation of the conflict was a dilemma for Moi because during the early years of independence he played an instrumental role facilitating the movement of outsiders into the Rift Valley and the acquisition of land on a willing buyer-willing seller basis.

Like many of Moi’s other sins of omission, the executive looked the other way in exchange for their continued support for the Kanu political machine.

The cynical, red in tooth and claw strategy was repeated on a smaller scale when Digo raiders attacked a police post in Likoni during the run up to the 1997 polls. In this case, the raiders were reportedly mobilised but then abandoned by a Mombasa tycoon entrusted with overseeing the Kanu electoral campaign on the coast. Although the Likoni raiders claimed as many coastal lives as upcountry Kenyan fatalities, this time the government launched a paramilitary operation on the pro-Kanu south coast that resulted in multiple cases of rape and other human rights abuses.

A colleague summed up the contradiction when he opined, “when these upcountry people disagree they slaughter each other, but when they are here they come together to grab our land and clobber us.”

The coastal people and pastoralists of northern Kenya would play a crucial role within Kanu by preventing the usual suspects from derailing the constitutional movement as a foreign-backed, opposition tactic to seize power.

The politics of the release phase falsified the hypothesis that Kenyan ethnicity is a function of deep-rooted primordial loyalties. Moi proved this by manipulating the personal ambitions and greed of Kanu opportunists, and then by using the same methods to exploit the shallow loyalties of opposition Members of Parliament. Jomo Kenyatta’s advice was finally sinking in: ‘Moi knows Kenyans’, Mzee had told his kitchen cabinet, ‘you only know Nairobi’.

In 1992 Kanu prevailed with a thin majority parliamentary majority. Moi responded by encouraging opposition member of parliament to defect to Kanu in turn for some material reward, typically a plot allocation. This served two purposes: it filled out the government benches while putting the hollow principles of opposition politicians on public display. The President pranked one particularly greedy Central Province MP who crossed the floor only to find that his reward was a public urinal on Accra Rd.

The politics of the release phase falsified the hypothesis that Kenyan ethnicity is a function of deep-rooted primordial loyalties. Moi proved this by manipulating the personal ambitions and greed of Kanu opportunists, and then by using the same methods to exploit the shallow loyalties of opposition Members of Parliament

Moi had played the role of reluctant agent of reform following the donor mandated return to multi-party politics, grudgingly agreed to the Inter-Parties Parliamentary Group reforms and the formation of an independent electoral commission before the 1997 polls, and assented to a people-driven constitution makeover after securing his final term in office.

Moi was a lousy dictator, but his final term in office turned out to be his finest moment as a politician. Over two decades Moi perfected the art of disorder as a political instrument. Now it was show time.

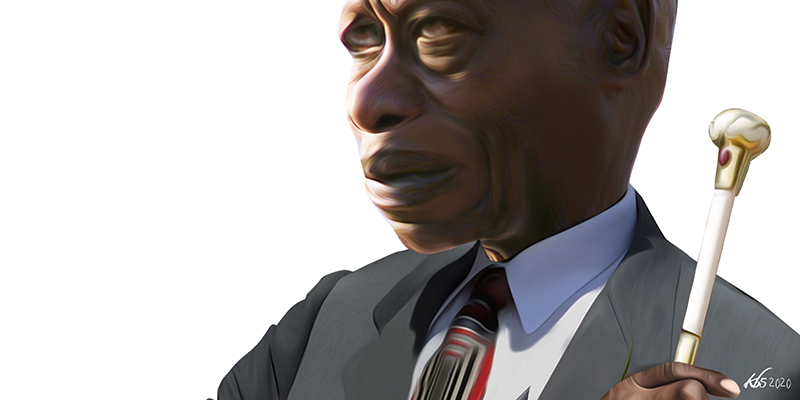

No longer weighed down with the burden of political survival, The Professor of Politics glided across the Kenya landscape repeating his epistles of unity and home-grown solutions to African problems. When Kanu and opposition MPs turned the constitution-making exercise into a battle over the positions at the top of the pyramid, Moi introduced Wanjiku, the eponymous working mother selling vegetables on the roadside, as the focus of the new dispensation.

Wanjiku became a permanent meme in Kenyan political discourse. Even many of his most committed opponents were conceding, ‘We can’t beat this guy’. Although the probability of a post-Moi Kanu victory in 2002 loomed large—it also depended on who would succeed the President. Moi saved his greatest feat of escapology for his final act.

Moi was a lousy dictator, but his final term in office turned out to be his finest moment as a politician. Over two decades Moi perfected the art of disorder as a political instrument. Now it was show time.

I have personally never witnessed a case of mass hypnosis that comes close to the public obsession generated by the Moi succession.

The drama began with the dismissal of his faithful Vice President, Professor George Saitoti, who was forced to hail a ride after leaving State House because his government car had been confiscated. Moi latter reappointed him, announcing the restoration during one of his roadside palavers. He whetted the appetite the state’s long time nemesis, Raila Odinga, by enticing his party to ‘partner’ with the government, then surprised everyone by dropping his loyal Kanu Secretary-General and selecting four Kanu vice chairmen to serve in his place. This effectively sent Raila to the back of the queue, at least for the time being.

Speculation about the successor dominated conversation in the nation’s bars, miraa sessions, offices, matatus, and private parlours. Unlike the ‘the msaliti affair’, which dragged out for several months, for the better part of three years Kenyans scrutinised every news broadcast, studied Moi’s body language, deconstructed the statements of Kanu functionaries, and subjected every clue and rumour to forensic analysis. Every possible scenario was debated.

In the end, Moi wrong-footed everyone again by choosing Uhuru Kenyatta as Kanu’s 2002 presidential candidate. Dubbed ‘The Project’ by Kanu insiders, the son of the founding father was a political novice whose electoral prospects faced formidable headwinds. Raila had already decamped to the opposition and three of the four vice-chairmen followed him.

The Project united the opposition at a moment when they were still struggling to do so among themselves. They finally prevailed on their third time around.

Reorganisation and Its Challenges

True to his promise, Daniel arap Moi retired to his farm. Before leaving office he declared that he had forgiven those who wronged him, and hoped that those whom he had wronged would do the same. His endgame earned him a large measure of redemption in the eyes of the public.

The overlapping nature of the system phases impart a fuzzy edged quality to the model used to frame this narrative. The reorganization phase was underway by the time Moi left office even though it would take another six years to complete and ratify the new constitution. Smouldering passions of the release phase fuelled the 2007-2008 post-electoral bonfire.

But it does help us extract some lessons about the dynamics of change in Kenya.

When I first started driving in Nairobi, I found that in on certain roads one had to go in the opposite direction to more efficiently reach the destination. The same contradiction applied during the Moi regime. Decentralisation in the form of the Rural Distract Focus, for example, actually strengthened control in the centre. The assault on forests, on the other hand, triggered the environmental movement and forced communities to actively monitor and assume greater ownership of their natural resource base. This idea was a hard sell before the 1990s.

Much of the praise for Moi was expressed as negatives: he kept the military out of politics, he avoided the very real possibility of civil war, and he did not meddle in the affairs of neighbouring countries. One counterfactual corollary of this pattern is the hypothesis that a well-managed post-Kenyatta Kanu would have supported a process of incremental reform, avoiding the slash and burn release politics of the Moi era.

When Kanu and opposition MPs turned the constitution-making exercise into a battle over the positions at the top of the pyramid, Moi introduced Wanjiku, the eponymous working mother selling vegetables on the roadside, as the focus of the new dispensation.

This may have resulted in either a lower threshold for change resulting in an extended conservation phase, giving way to a considerably harsher process of release, as has been the case in other eastern African countries. Even knowing what we know now, many would still choose Moi over a release phase Mbiyu Koinange, Oginga Odinga, or Charles Njonjo Presidency.

Moi left an ambivalent legacy. His public persona was a composite of Paretto’s political elite dialectic. The persuasive Swahili speaking Fox who connected with the masses contrasted with the populist and xenophobic English speaking Lion who provide a soft target for Western critics. The regime’s excesses generated the equal and opposite reaction resulting in the push for the comprehensive constitutional makeover. He also fostered the political culture of tricksters and masks that contributed to the electoral trauma overtaking the 2007, 2013, and 2018 national polls.

During the days following Moi’s departure, Kenyan journalists have produced a body of reportage, personal vignettes, opinion pieces, recapitulations of the human rights carnage, and Moi era historical perspectives. The revisionism of some elders reopened many wounds.

These backward looking accounts, the-good-Moi-bad-Moi debate being waged on social media, and the yaliyopita ni ndwele nostalgia of television talk shows are peripheral to the new challenges of the reorganisation phase.

John Ilife’s short book, The Emergence of African Capitalism, ends with a useful comment on the role of agency in Africa’s transition to a distinctively Indigenous capitalism. It is certain,” he states,” that in determining whether or not African capitalism can establish itself as a creative force, political skill on both sides will be crucial.”

Because the private sector was dominated by the Gikuyu and the small Asian community, Moi’s policies effectively inhibited the private sector’s growth until liberalisation forced him to make a choice in 1989. He chose the Asians, a choice that reinforced the Gospel According to Saint Mark primitive accumulation, inhibiting Schumpeter’s creative destruction of capitalism now emergent across the region.

Much of the purloined assets and rent-seeking that took place after independence has not contributed to formal sector progress, leaving the more adaptive informal sector to absorb most of the unprecedented numbers of young Kenyans entering the economy.

The current phase of regional capitalist penetration comes with a new cast of international actors with the Chinese in the front rank of a new array of regional states that include the UAE, Turkey, India and other new actors establishing a foothold in the Horn of Africa’s political economy. The “both sides” equation is changing, and it will take more than Illife’s creative indigenous capitalism to unlock Africa’s potential.

Reorganisation and the Case for Game Change

Release can lead to diverse outcomes from socioeconomic transformation to collapse, or retreat back into the conservative order. Kenya’s reorganization is at an early stage. It will subsume a new set of challenges and opportunities that will require not only updated political skills, but also a sophisticated understanding awareness of the forces in play.

The world appears to be undergoing a release phase across system scales that is raising questions about the civilisational order generated by win-lose capitalism. There are deep conversations taking place around the world focusing on the array of post capitalist concepts and tools for addressing a range of contemporary issues.

Examples include market based valuations of ecological services, endemic racism and right wing populism, artificial intelligence, profit seeking health care, climate change and resource scarcities, the impact of social media impacts on political processes, and our conflict sustaining security frameworks. There are many others feeding into the new values-based narratives emerging across the planet.

The diagnoses of Frantz Fanon, Kwame Nkrumah, Samir Amin, Walter Rodney, Julius Nyerere, Amilcar Cabral, and other anti-imperialists of that era were not so much incorrect as they were limited by neo-Marxist dirigisme of the exploitation-conservation phase overlap.

Kenya’s transitional incoherence is too complex to support an equally dirigiste Dubai or Chinese style developmental template. But it’s size, organisational diversity, and a resilience bred out of chronic uncertainty gives it an advantage over the large polities that for generations have dominated the world. Rwanda’s progress is a case in point.

The diagnoses of Frantz Fanon, Kwame Nkrumah, Samir Amin, Walter Rodney, Julius Nyerere, Amilcar Cabral, and other anti-imperialists of that era were not so much incorrect as they were limited by neo-Marxist dirigisme of the exploitation-conservation phase overlap.

Moreover, Kenya’s demographic structure comes with a forward-looking orientation that can support a localised variation on this discourse of collaborative creativity and its problem solving applications. To do so, however, our millennials will have to broaden their intellectual horizons and adopt the game-changing mind-set needed to hack the instrumentalities driving the quasi-reorganizational thinking behind debt magnets like LAPSSET and Vision 2030 centralised planning.

Several months after the 1997 elections I was crossing Harrambee Avenue when the President popped up in a land rover. I will never forget his spontaneous address to the small crowd that gathered: “Hiyo katiba tutarakebisha, lakini nataka nyinyi wananchi mukumbuke kwamba hata katiba haiwezi kuzuia shari ndani ya moyo wa binadamu.”

“We will overhaul the constitution, but I urge you Kenyans to remember that even a new constitution cannot restrain the evil in men’s hearts.” Game on.