After more than 30 years of ruling Sudan, in April 2019 the dictator Omar al-Bashir was finally deposed by the military following an irrepressible explosion of civil unrest. In less than five months of protest following the intolerable austerity politics imposed by al-Bashir’s administration, the Sudanese population found unexpected energy and cohesion in fighting peacefully to obtain a democratic government. As crowds of demonstrators from all across the country converged on the capital to join the civil movement, art flourished, and a renewed sense of freedom gave voice once again to those who found the strength to break their chains. Women, such as the “Nubian Queen” Alaa Salah (dubbed “the woman in white”), have been at the forefront of the demonstrations, and people from all walks of life who have been denied their basic human rights rose to finally end their silence.

However, things went south in June when the army refused to hold its promise to guarantee a three-year transition period before a new civilian rule could be established. Although the protest organisers rebuked the military’s decision to scrap the agreement, the Transitional Military Council (TMC) acted with unexpected brutality, killing more than one hundred Sudanese activists during the Khartoum massacre. Today, the situation is extremely tense, with claims that the United Arab Emirates is arming the violent counter-revolution. Furthermore, back-and-forth negotiations after a general strike have brought the whole country to a halt. While it’s still hard to tell when (and if) normality will return to the country, let’s have a look at what has happened so far and what the future may hold for Sudan in the post-al-Bashir era.

11 April 2019 – The despot is overthrown

After succeeding former Prime Minister Sadiq al-Mahdi in 1989, Omar al-Bashir didn’t lose much time to show the world his true face as a violent and brutal leader. Al-Bashir has been indicted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for war crimes and crimes against humanity. He has been accused of being the man behind the mass murders, forcible transfers, tortures, and rapes committed in Darfur since 2003.

When in January 2018 the country started facing imminent economic collapse, al-Bashir decided to impose a series of extreme austerity measures that included cuts to wheat and electricity subsidies, and the devaluation of the country’s currency. Inflation spiked to 70 per cent, and the Sudanese people had to struggle even to access basic goods, such as fuel, bread, and cash from ATMs. When the first demonstrations over the unacceptable living standards began in the eastern regions (the price of bread tripled in less than one year), the situation quickly became uncontrollable.

In December 2018 the unrest spread to the capital Khartoum and took the form of a series of riots that were brutally repressed by the regime. Nearly a thousand protesters were arrested, and dozens more got killed or wounded by the security forces who used live ammunition against the population. Coordinated by the Sudanese Professionals Association (SPA), demonstrators from all social classes of the country eventually joined forces under the umbrella of the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC) – also known as the Alliance for Freedom and Change – to fight for the ouster of the regime and the transition to a democratic government. Despite many attempts to block media coverage of the protests and to impose strict Internet censorship on social media, al-Bashir’s administration failed to contain the civil movements.

When in January 2018 the country started facing imminent economic collapse, al-Bashir decided to impose a series of extreme austerity measures that included cuts to wheat and electricity subsidies, and the devaluation of the country’s currency. Inflation spiked to 70 per cent, and the Sudanese people had to struggle even to access basic goods, such as fuel, bread, and cash from ATMs.

The tension peaked in February 2019 when the president went so far as to declare a state of national emergency – an attempt to try and break the will of the protesters with more violence, beatings, and arrests perpetrated by army officers who were put in charge of provincial governments. But the Sudanese protesters did not relent, and on April 6 hundreds of thousands of them marched to the square in front of the military’s headquarters, seeking the help of the army. A conflict between the military who took the demonstrators’ side and the security forces ensued, and shots were fired. On April 11, 2019, the military finally announced that al-Bashir had been overthrown.

The many shapes and colours of the civil protest

Thirty years of suffering under the weight of al-Bashir’s regime have not been enough to drain the Sudanese people of their desire to be free. The protest drew people from all ages, social classes, religions, and colour. They overcame social and economic barriers, and joined forces under the same banner.

During the hardest times of the civil battleground, the revolt harboured some heroic moments, such as when a doctor was killed while he was bravely trying to resuscitate other protesters who were wounded by the security forces. The marches were led by courageous women who took a stand against the oppressive colonial laws that condemn to flogging all female activists who participate in anti-government manifestations. The image of Kandake Alaa Salah chanting to encourage the protestors went viral and came to symbolise women’s strength in leading this battle to live in a country where everyone’s human rights are protected.

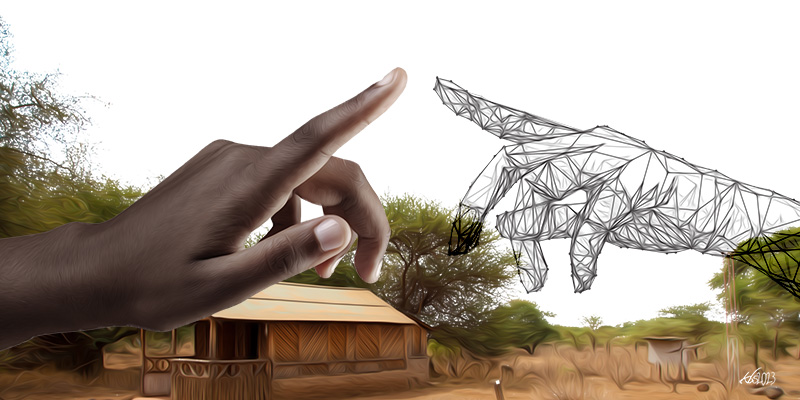

The civil unrest channeled incredible and unexpected energy from the Sudanese population – an unbreakable will to peacefully fight against oppression that provided the entire continent with a fundamental lesson on civil disobedience. Neither the scorching heat, hunger, nor thirst stopped the Muslims protesters from enduring their sit-ins in front of the army headquarters in Khartoum during Ramadan. The same social media that the government tried to muzzle became the instrument used by the volunteers who assisted these determined dissidents by providing them food and water at night. And as the revolution never stopped or faltered under the blows of the regime’s forces, all this energy became palpable and took the form of colourful murals, amazing canvases, manifestos on women’s rights, and other incredibly beautiful works of art that left the word astonished. And very few things are more exquisitely humane and liberating than art itself.

The betrayal by the TMC and the Khartoum massacre

Following the deposition of al-Bashir, power was assumed by the Transitional Military Council (TMC), a council of seven generals led by Lt-Gen Abdel Fattah Abdelrahman Burhan. Once it seized power, the TMC held its position firmly, claiming it must stay in charge to ensure order and security. A long and difficult negotiation with the FCC ensued before an agreement could be reached on May 15. The agreement provided for a 3-year transition period to a civilian-led government constituted by a sovereign council, a cabinet, and a legislative body. The long transition period was needed to dismantle the deeply entrenched political network previously established by former President al-Bashir and ensure fair, democratic elections.

The civil unrest channeled incredible and unexpected energy from the Sudanese population – an unbreakable will to peacefully fight against oppression that provided the entire continent with a fundamental lesson on civil disobedience.

However, a few days later, something terrible happened. A new (or we should say, old) force made its appearance among the Sudanese soldiers. Groups of masked militiamen started beating activists and dragging them away to secret detention centers where they are held without charge and sometimes even raped and tortured. Hit squads move around the city in Toyota pickups with their plates removed to chase down protesters.

Who are these people? They’re the same elite squads of security forces employed by the now ousted al-Bashir regime to clear out protesters from the streets. Named the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), they’re highly-trained, exceptionally brutal agents able to exact swift punishment on anyone who endangers their control on the Sudanese people and the country. They are the feared Janjaweed, a group of specialised forces famous for the atrocities inflicted on the civilian population during the Darfur crisis 14 years ago.

The TMC went so far as to arrest and forcibly deport three rebel leaders – Yasir Arman, Ismail Jalab and Mubarak Ardol – to South Sudan after they met Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed for talks about the negotiation. Their goal is clear – the do not intend to hand over power to the people. The military elites simply ousted al-Bashir as they saw a unique opportunity to seize power for themselves, and they came clean on this on June 3 when several armed bands opened fire on the protesters with the excuse of “dispersing the sit-in”.

However, a few days later, something terrible happened. A new (or we should say, old) force made its appearance among the Sudanese soldiers. Groups of masked militiamen started beating activists and dragging them away to secret detention centers where they are held without charge and sometimes even raped and tortured.

They didn’t stop there. Over 200 military vehicles and 10,000 soldiers ravaged and ransacked the city for several days while the Internet was shut down. Countless unjustified arrests were carried out, and unarmed people were dragged out of their houses, detained, beaten, and raped. The aftermath was a bloodbath – aptly named the Khartoum massacre, with more than 100 Sudanese activists killed, nearly 700 wounded, and at least 70 women and men raped by the RSF and Janjaweed forces. (Many corpses have been thrown in drainage channels so the body count is probably even higher.) Shortly after the violent crackdown, the military council thrashed any agreement made with the FCC and SPA and announced that fresh elections would be held within nine months.

The general strike and total civil disobedience

In the wake of the killings, civilian activists haven’t given up with their quest to establish a democratic government in Sudan. The “people’s movement” may lack the cohesion and discipline of the reorganised military party, but it definitely doesn’t lack the will and determination to make the change. While the international community’s response has been the usual generic condemnation, the rebels swiftly understood that big powers, such as the United States, China and Europe, could do nothing more than ask their regional allies to exert (negligible) pressure on the Sudanese army. Even the hands of the United Nations are somewhat tied after China and Russia blocked the sanctions that were initially foreseen. The FCC thus defiantly cut all contacts with the TMC and called for a general strike – “total civil disobedience” – to kick the military junta out.

Observance of the strike was nearly absolute, reaching almost 100 per cent in Khartoum. All across the country all kind of operations, from banks, to hospitals, airports, ports, and government agencies, have been shut down for days. Workers are protesting side by side with scientists, doctors, lawyers, shop owners, street vendors, and journalists. The entire country is once again united against a common threat.

But the reprisal was swift and cruel, with dozens of airport workers arrested and hundreds of people detained without charge. Despite its attempts at distorting the truth through propaganda, the RSF now looks more and more like an army of occupation than a force that is guaranteeing civil order and security.

The current situation and the reaction of the international community

The commander of the RSF, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (widely known as “Hemeti”), is a ruthless veteran of the war in Yemen – his RSF troops are still fighting there to help the Saudi-led coalition. For obvious reasons, he is backed by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates who do not want see a major Arab country like Sudan transition to democracy. The Saudis and the Emiratis know that he is the ideal candidate to preserve the autocratic status quo in Sudan after the fall of al-Bashir, and have already warned against the “folly” of a popular uprising. They have explicitly expressed their support for Hemeti and other military leaders. Several videos uploaded on social media clearly show that the militiamen who carried out the killings during the June 3 attack were geared with Emirati-manufactured armaments.

The United States’ reaction was cautionary at best. The Under-Secretary of State for Political Affairs, David Hale, expressed concern over the crackdown during a talk with the Saudis, noting “the importance of a transition to a civilian-led government”. A diplomat will be sent to ease the talks between the FCC and the TMC, but so far, no real pressure has been exerted on Egypt or the Saudis to act against the TMC forces or to help the FCC.

The commander of the RSF, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (widely known as “Hemeti”), is a ruthless veteran of the war in Yemen – his RSF troops are still fighting there to help the Saudi-led coalition. For obvious reasons, he is backed by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates who do not want see a major Arab country like Sudan transition to democracy.

After initially supporting a transition towards civilian rule, the African Union (AU) spoke against the intervention of international actors in the current Sudanese situation. But the AU’s chairperson is none other than Egypt’s President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, the Field Marshal who won elections with a landslide victory by obtaining 97 per cent of votes. It is not a coincidence that el-Sisi seized power after his army massacred 1,000 unarmed protesters at a sit-in in Cairo in 2013.

Now, after days of talks, Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed finally managed to broker a new agreement between the civilian and military forces. On 12 June, the strikes were momentarily suspended after the TMC agreed to release political prisoners, and the two parties are now at the negotiating table once again. The situation is extremely unstable, and the TMC is starting to feel the pressure of internal divisions. What the future holds for the Sudanese people is really hard to tell, but their defiant battle against all odds is a prime example of the immense power that common people unknowingly hold against their oppressors.