In the Jubilee universe, it is almost an article of faith that politics is “bad” and development is “good”. It’s not uncommon to hear President Uhuru Kenyatta, Deputy President William Ruto, and high-level administration officials and their supporters’ constant put-downs directed at their opponents: “We don’t have time for politics, we are only interested in development.” They believe that the depoliticisation of development is necessary in order for them to deliver on their campaign promises.

While such a rhetorical sleight of hand is occasionally designed to silence opponents – who are supposedly opposed to development – in practice, it also reveals the Jubilee government’s limited understanding of politics. For them development is a cold, apolitical, technical exercise that is not only immune to politics, but transcends it.

More broadly, Jubilee’s politics-development dichotomy is an insidious attempt at redefining politics as criticising Jubilee, whether fairly or unfairly, and development as praising the administration, whether they are delivering or not. The net aim is to induce self-censorship among critical voices.

Techno-fallacy

Building a rhetorical firewall between development and politics is not a new idea; President Daniel arap Moi’s favourite retort when placed under pressure was “Siasa mbaya, maisha mbaya” (bad politics, bad life), never mind that under him, Kenya was firmly in mbaya zone. Maisha was so mbaya under Moi that economy growth was a mere 0.6 per cent when his successor Mwai Kibaki took over in 2002. Dissent was penalised and the country felt like a band that was dedicated to singing his praises. It is rather ironic that Jubilee, which would like to be remembered for good economic stewardship, would look to Moi for inspiration.

Building a rhetorical firewall between development and politics is not a new idea; President Daniel arap Moi’s favourite retort when placed under pressure was “Siasa mbaya, maisha mbaya”

The Jubilee government has also coupled the depoliticisation of development with a similar rhetoric on technology, in the process completely eviscerating nuances, complexities or grey areas when discussing public policy. You are either part of the cult of technology or you are not interested in progress.

In his book, To Save Everything, Click Here: The Folly of Technological Solutionism, Evgeny Morozov captures Jubilee’s approach to development: “Recasting all complex social situations either as neat problems with definite, computable solutions or as transparent and self-evident processes that can be easily optimised — if only the right algorithms are in place! — this quest is likely to have unexpected consequences that could eventually cause more damage than the problems they seek to address.”

For instance, one of Jubilee’s bright ideas of fixing the education system is to provide every child with a laptop, in line with their emphasis on learning science, technology, engineering, and mathematics as opposed to the humanities, which they see as not “marketable”. Never mind that only slightly over half of Kenya has access to electricity, that the teachers have not yet been trained or hired for the switch to using laptops, and most schools do not have computer labs. Jubilee is, after all, led by the dynamic digital duo that needs everyone to be wired.

Along with a blind faith in technology, Jubilee also regards corporate experience as a most prized asset in public appointments – as exemplified by the Harvard-educated former Barclays CEO, Adan Mohamed, who is the Cabinet Secretary for Industrialisation. For Kenyatta and his ilk, corporate experience, when coupled with technology, will fix pesky inefficiency and sloth in the public service.

This is not new; under pressure domestically from opposition groups, and externally from the Bretton Woods institutions, Moi appointed a “Dream Team” to key public offices. The officials were drawn from the private sector, international finance and development organisations. The group was led by Richard Leakey (the famous paleoanthropologist and former head of the Kenya Wildlife Service who had even formed a political party to oppose Moi in 1990s), who was appointed as the Secretary to the Cabinet and Head of the Civil Service. Martin Oduor-Otieno, a former director of finance and planning at Barclays Bank, was appointed as the Permanent Secretary in the Ministry of Finance and Planning and Mwangazi Mwachofi, the resident representative of the South Africa-based International Finance Corporation, became the Finance Secretary.

Along with a blind faith in technology, Jubilee also regards corporate experience as a most prized asset in public appointments – as exemplified by the Harvard-educated former Barclays CEO, Adan Mohamed, who is the Cabinet Secretary for Industrialisation. For Kenyatta and his ilk, corporate experience, when coupled with technology, will fix pesky inefficiency and sloth in the public service.

While Moi was boxed into a corner and had no option but to cater to donors’ wishes, Jubilee’s appointment of well-credentialed public officials from the private sector is an attempt to demonstrate that the government is using corporate best practice principles to manage the public sector. However, the appointment of individuals with private sector or international expertise is rooted in a lack of appreciation for received bureaucratic wisdom; it is a system of faceless, unelected officials keeping the state’s institutions humming along and ensuring continuity from one administration to another.

For Jubilee, bureaucracy is a dirty word. Both under Moi and under Jubilee, the credentialed senior public officials failed to deliver, although on balance, Moi’s cabinet, which had more court poets than individuals with diplomas from good schools abroad, did better.

Grievances and greed

Jubilee’s weaponisation of optics and breathless spin was honed when Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto – the two principals in the Jubilee coalition – were indicted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for their alleged role in 2007-2008 violence.

Ruto and Kenyatta make an unlikely political team. The latter is a prince of Kenya’s politics and the former is a self-declared “hustler”. Even when considering Kenya’s shape-shifting political landscape and allegiances, the two couldn’t be more different.

But they were brought together by grievance and greed. They regarded their prosecution at the International Criminal Court as a witch-hunt; they argued that the two top presidential candidates during the 2007 election that led to violence and displacement were former President Mwai Kibaki and former Prime Minister Raila Odinga.

During the course of their indictments, the duo skillfully used social media and established themselves as bona fide underdogs. As a result, they refined their enduring ability to generate sometimes pugnacious, if not altogether needless, spin, which had tremendous traction with their base. Ruto and Kenyatta cast the ICC as an imperial project bent on getting them, effectively framing themselves – not those killed, maimed or displaced – as the victims of the post-election violence. Their spin was so effective that even some of the victims of the violence held “prayer rallies” for them.

In fairness, some of the reputational damage experienced by the ICC was self-inflicted. When I visited a IDP camp in Nakuru in 2011, one of the IDPs told me that the ICC’s Chief Prosecutor, Moreno Ocampo, had no time to visit them, and was busy doing safaris in Nairobi National Park.

During the course of their indictments, the duo skillfully used social media and established themselves as bona fide underdogs. As a result, they refined their enduring ability to generate sometimes pugnacious, if not altogether needless, spin, which had tremendous traction with their base. Ruto and Kenyatta cast the ICC as an imperial project bent on getting them, effectively framing themselves – not those killed, maimed or displaced – as the victims of the post-election violence.

The ICC was not the only victim of Jubilee’s rage; Raila Odinga, the cottage industry of upstart politicians, felt the full weight of Jubilee’s relentless propaganda blitzkrieg, part of it also emanating from his support for the ICC process, which Ruto, his lieutenant in 2007, interpreted as throwing him under the bus. (Ruto was a leading member of Odinga’s team during the 2007 election.)

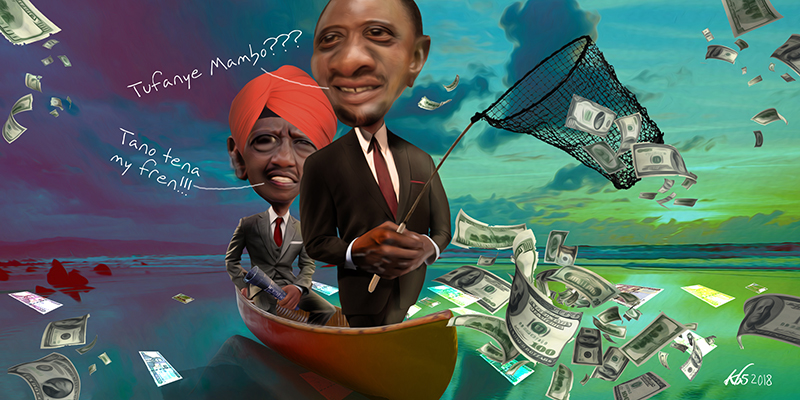

After claiming some big domestic and foreign scalps, Jubilee started believing is own hype. While many dismissed Jubilee’s breathless social media campaigns during the elections as a passing fad once the cold reality of governing sets in, for Jubilee social media was the system. Beyond the hype, any critical assessment of Jubilee’s grand ideas, such as a 24-hour economy, 9 international standard stadia, and 21st century public transport, would show that they are all sizzle and no steak. The large-scale infrastructure projects were mostly designed as a gravy train, as the Standard Gauge Railway amply demonstrated.

Politics of shamelessness

The tissue that connects the depoliticisation of development, the blind deployment of technology, and the professionalisation of the cabinet is Jubilee’s shamelessness. No political party is without faults and foibles, but in Jubileeland, shamelessness has taken an insidious form. The shamelessness here is not the kind citizens have come to almost expect from the politicians; in Jubilee’s case, it is its modus operandi, a blunt object to hit opponents with. The lack of shame has not only been adopted by Kenyatta and Ruto, but also by their close lieutenants.

When the presidential results were announced two days after the annulled August 8, 2017 election, demonstrators and the police engaged in a running a battle in the Mathare slum in Nairobi. Police used live bullets and killed both demonstrators and bystanders. I spoke to some of the families of the victims and corroborated their stories with medical records and family witnesses.

The tissue that connects the depoliticisation of development, the blind deployment of technology, and the professionalisation of the cabinet is Jubilee’s shamelessness. No political party is without faults and foibles, but in Jubileeland, shamelessness has taken an insidious form.

But on August 12, at a press conference, the then Acting Internal Affairs Cabinet Secretary, Fred Matiangi’ denied that police had shot and killed people. He stated, “I am not aware of anyone who has been killed by live bullets in this country. Those are rumours. People who loot, break into people’s homes, burn buses are not peaceful protesters.” Yet it is not that Matiangi’ did not have access to the details of the people killed, some of whose deaths have been recorded in government hospitals and by the media and human rights groups.

Jubilee learnt some of this shameless spin from Moi’s Kanu party. In 2000, when drought was ravaging parts of Northern Kenya, the then government minister, Shariff Nassir, denied there was drought when pressed in Parliament by one of the area MPs. A few days later, the government declared a famine in Kenya.

President Kenyatta says that fighting corruption will be a key pillar of his legacy. The Auditor General’s Office has done more than any other state organ to reveal the level of corruption in government agencies through audit reports. In an ideal world, you’d think that the president would consider the Auditor General’s Office as a key ally. But the president scoffed at the Auditor General’s plan to investigate the activities of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York in relation to the alleged misuse of $2 billion Eurobond cash that Kenya raised in 2014. The president was quoted telling the Auditor General, “When you say that the Eurobond money was stolen and stashed in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, are you telling me that the Kenyan government and United States have colluded?” The president then insinuated that the Auditor General, Edward Ouko, was stupid. Never mind that the president’s remarks came during a State House anti-corruption summit. It is also likely that the story of the missing Eurobond money will be the story of Jubilee’s corruption.

Lack of shame is dangerous when it comes from a place of entitlement – the #Mtado? phenomenon. Which naturally breads impunity.

David Ndii wrote, “Jomo Kenyatta’s regime was corrupt, illiberal and competent. Moi’s was corrupt, illiberal and mediocre. Kibaki’s was corrupt, liberal and competent. So, Moi scores zero out of three. Jomo scores one out of three. Kibaki scores two out of three.”

The original sin after 2010 constitution was promulgated was when a court ruled that Kenyatta and Ruto could contest the 2013 elections despite being indicted by the ICC. This officially killed Chapter Six on leadership and integrity of the Katiba, which effectively set Kenya down the path of “anything goes”.

Lack of shame is dangerous when it comes from a place of entitlement – the #Mtado? phenomenon. Which naturally breads impunity.

Kanu and Jubilee have ruled Kenya longer than any other party, and in the process have created the Kenyatta and Moi family and business dynasties. When under pressure, it is not uncommon to see Kenyatta and Jubilee seek Moi’s eternal wisdom. The visits to Moi’s home are done at the exclusion of William Ruto, which sets up 2022 neatly as the battle between the princes and the hustler.

Raila was a key player in the 2002 elections, and in 2013, Ruto was a key player in defeating Raila. In 2022, Ruto could face Raila’s fate. While Ruto’s defeat could delight many, the techno-dignified political opportunism that is Jubilee, which is illiberal, incompetent and corrupt, will endure.