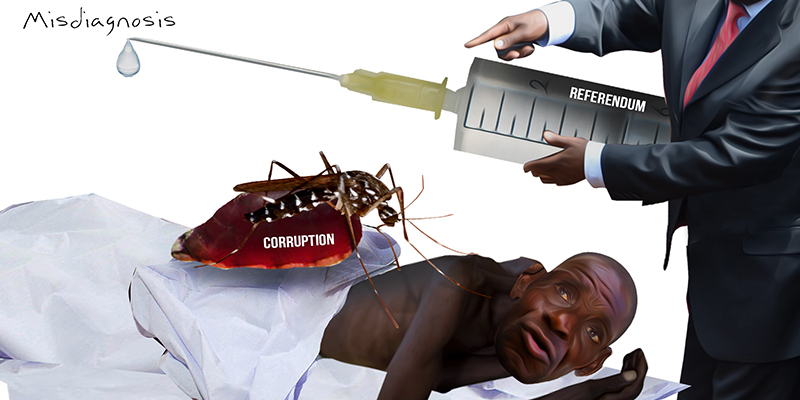

The history of Kenya is a story of distracting the people of Kenya from fundamental economic reforms that would allow the Kenyan people to participate in their economy and have institutions that serve them, rather than serve the interests of Western capital and its local caretakers in government. The latest referendum push led by Raila Odinga, against our will, despite claiming otherwise, is just the latest installment in the process of scuttling economic and social reforms.

And yet, Raila’s insistence on a referendum to restructure political power is, strangely, a fulfillment of his father Jaramogi Oginga Odinga’s principles. Until recently, I held onto the romantic notion that Jaramogi was interested in fundamental social reform, and was opposed to the capitalist and feudal accumulation of wealth by the Kenyatta family and their fellow ethnic elites. That was until I stumbled about the work of Nicola Swainson, author of The Development of Corporate Capitalism in Kenya, 1918-1977. I now understand what Julius Malema calls the “arrangement” of Kenya very differently from before.

To understand the Jaramogi paradox, one must first go back to what happened with colonialism and independence. According to the popular story of independence, the Mau Mau peasants fought against foreign domination, and now Kenya is an independent country. An increasingly popular amendment to that narrative is that Jomo Kenyatta was never part of the Mau Mau, and that is why, after independence, he betrayed the Mau Mau cause, protected the white settlers and became a version of them. An additional amendment is that Jaramogi understood that it was “not yet uhuru,” and that by forming the Kenya People’s Union with Bildad Kaggia, he sought to promote land reform and politics based on issues, not identity.

Thankfully, more Kenyans are beginning to understand that the first president was never interested in freedom. But what remains is our view of the Europeans as all sharing the same interests. Understanding the different European interests is key to understanding what exactly Jaramogi stood for, and how Raila’s politics do conform to Jaramogi’s position, but at the same time do not serve the interests of Kenyans.

As Swainson explains, the settlers, the British government and the British corporations were all serving different interests. When the British East African Company landed in Kenya, it did not have white settlers in mind, and in fact, it only supported their stay in Kenya on the understanding that what the settlers would produce on the land would serve British corporations at home.

Thankfully, more Kenyans are beginning to understand that the first president was never interested in freedom. But what remains is our view of the Europeans as all sharing the same interests. Understanding the different European interests is key to understanding what exactly Jaramogi stood for, and how Raila’s politics do conform to Jaramogi’s position, but at the same time do not serve the interests of Kenyans.

However, the settlers didn’t play to script. They consistently fought against the colonial government’s control of land, agriculture and trade, and towards the 1950s, they were getting more control of agriculture and trade in the colony. But the Achilles heel of the settlers was that they still needed the colonial government’s military might to force Africans off their own land, and to work on the colonial farms.

After the Second World War, the British homeland needed more resources for its recovery and started to put more pressure on the colonial government to expand the extraction of resources from the colonies. For more resources, the colonial government needed to expand trade and land ownership to Africans, and encourage the growth of an African middle class to help the British corporations. But the settlers would have none of it. As a result, the colonial government had a hard time pleasing both the settlers here and the government back home.

The stalemate ended in the 50s, when the peasants revolted against the settlers.

Of course, the settlers did not have the firepower to crush the rebellion, and so the British government sent its troops. But once in charge, the British government pressed the settlers to concede to more African involvement. This move allowed the British state and corporations to weaken the hand of the settlers and to strengthen their own. It also allowed more space for the compromised African elites who would not ask for radical social reform. Companies like Brooke Bond and East African Breweries, and later on Bamburi Cement, consolidated their positions in Kenya as the clueless Jomo Kinyatta initially told Kenyans that since the British were leaving, we could have the land back.

Jaramogi began his career before independence intending to be a businessman. As he explains in his book, Not Yet Uhuru, his initiation into politics came from the realisation that the British were putting obstacles in the path of African capital. African land was community-owned, which meant that Africans could not borrow loans because they did not have title deeds. Africans couldn’t form cooperatives unless the colonialists controlled the cooperatives. Africans couldn’t get credit and couldn’t buy shares. Africans couldn’t set up businesses in the towns, only in the “bush”. Town trading, even in Kisumu, was reserved for Asians.

The colonial government justified all this micro-managing of African entrepreneurship in the name of Africans needing to be protected from going into debt (the irony!). Jaramogi, therefore, understood that the obstacles to African capital were racial and political. He decided to join politics, because, in his words, “politics was the only sphere [of African advance] approved by the government.” That was when he quit teaching and ran for a seat in Central Nyanza African District Council. Thus Jaramogi entered politics as an indigenous capitalist.

At independence, Jaramogi would rudely discover that the fault lines of access to capital simply shifted from race to ethnicity. The Kikuyu elite fixed the economy so that even though Western corporations would continue to exploit the country, it was only the Kikuyu elite who could share in the exploitation. In other words, entrance into the comprador elite group was necessarily ethnic.

And, as Swainson explains, the Kenyatta government set into motion a series of laws to control access to capital. Laws required the British multinational corporations to employ African managers and board members, and to give them shares. One cabinet minister, whom Swainson doesn’t name, was so notorious for demanding ten percent of the start-up capital of Western multinational that he got the nickname “Mr Ten Per Cent.” In 1975, the government wrote laws that allowed African elites to seize the businesses of Asians, and even though the law talked of non-citizens, Asians who were Kenyan citizens also lost their businesses.

At independence, Jaramogi would rudely discover that the fault lines of access to capital simply shifted from race to ethnicity. The Kikuyu elite fixed the economy so that even though Western corporations would continue to exploit the country, it was only the Kikuyu elite who could share in the exploitation. In other words, entrance into the comprador elite group was necessarily ethnic.

So Jaramogi understood that it was not yet uhuru, and that the transactional economic relations between the exploited peasants and Western capital hadn’t really changed. Western capital had simply fired colonial settlers and replaced them with African (Kikuyu) elites to help Western capital to continue exploiting the majority of Kenyans. In other words, independence was just about replacing white chief executive officers with black ones and putting some black faces on the board – but the companies were still foreign-owned. And, as we now know, it was more difficult to fight against the black “nyapara” for Western capital, because they used ethnicity to erase the class distinctions between themselves and the ordinary Kenyans.

Since then, the obsession of Jaramogi and now of his son, is to reform this political set- up so as to open up the economy. The referendum is part of first seeking the political kingdom, with the promise that the economy will be added to it as well.

But in this 21st century, we need to refuse the formula of one first and the other later. We must fight for the economy now.

Jaramogi’s experience highlights the problem that we still have today. It’s difficult to make money if you are not in politics. The laws and economy are structured so that if you’re not a politician, or if you do not have politician friends, you can barely make it as an “entrepreneur”. And if you’re not a Kikuyu connected to the Kenyattas, it is even harder for you to join the elite. All you can do is negotiate with the Kenyatta elite or its ethnic representatives.

However, this relationship between politics and economics is now a catch-22 because you need money to run for office in order to be in a position to grow your business. This means that without education, poor people stand a slim chance of social mobility, unless they find the formula to steal. And stealing means that you can never go to jail because you have enough to bribe a judge, assuming charges are leveled against you in the first place.

Since independence, the role of the political class (almost synonymous with the Kikuyu elite), with the help of Western governments, has been to keep performing elections and ethnic politics to blind us to this reality. In the name of reform, they make Kenyans obsessed with the mathematics of the ethnic composition of government and probabilities of electoral success so that the Western capital involved in our exploitation continues to remain faceless and we do not see politicians as a mere comprador elite getting their 10 per cent.

That is why Kenya has gone through a succession of political reforms that do not fundamentally change the economic arithmetic. In 1963, KADU crossed the floor. We repealed Section 2A of the constitution and re-introduced multiparty elections three decades later. In 2005, we had a referendum. In 2008, a coalition government. In 2010, as a result of the chaos of 2008 and pressure from the international community, we finally got a constitution that puts the Kenyan people at the center of governance.

But with this last reform, some things have changed, although not nearly enough. With devolution, the people are starting to see fundamental changes that they had not seen for the previous fifty years. We have also now got bolder in demanding public participation in policy and governmental institutions. Kenyans are now demanding more, and are even more adamant about it.

Unfortunately, that is not what the political elites on either side want. Of course, the Kenyatta family maintains an interest in the status quo, where it controls the economy and reduces elections to a joke whose purpose is to justify why Western corporations must still trade in Kenya since Kenya has a “democracy”. Their son is sinking us into debt simply because he wants to build infrastructure and exploit our labour for capital.

In addition, the institutions of this country are still solidly colonial. The politicians and their political appointees in government bodies still plan the country and the economy as if we Kenyans don’t exist. For example, healthcare reforms have not been to treat Kenyans, but to encourage medical tourism and Kenyan doctors trained by our taxes go abroad so that they can send remittances. Meanwhile the government imports a handful to Cuban doctors as a way of showing the finger to Kenyan ones.

Foreign ideas and foreigners have driven the recent education curriculum reforms, and the contempt for Kenyans is so bad that the government would only recognise the problems we have been talking about after they hired foreign experts to tell them the obvious. Land is being given away to foreign landowners in Laikipia and Isiolo, with Africans branded as threats to wildlife, which needs wazungu to conserve the environment.

Our politicians have become so predatory that when our health is threatened by poisoned sugar, their first worry is that Western tourists and investors might hear the truth and not bring their money to Kenya.

Even politicians’ wives repeat the contempt for African Kenyans. The Kenya government organised Melania Trump’s visit to orphaned human and animal children, and the US First Lady wore colonial settler costume. In other words, Kenya is a country of no people, or no adults. Children have no parents and the job of the elite is to help the West help us.

Our politicians have become so predatory that when our health is threatened by poisoned sugar, their first worry is that Western tourists and investors might hear the truth and not bring their money to Kenya.

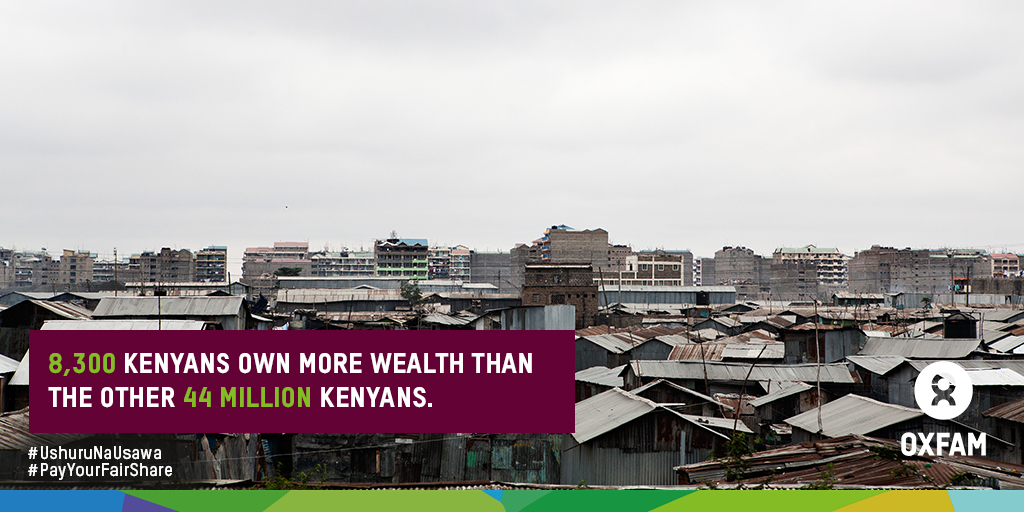

And for all these insults, all we get is managerialist lip service to Kenyans through plans like Kenya Vision 2030 and the Big 4 agenda. The fancy strategic plans have not prevented inequality from growing at a rate faster than before. According to Oxfam, 8,300 Kenyans own more wealth than the bottom 99.9 per cent (more than 44 million of us). Kids are still not going to school, and healthcare is still out of the reach of most Kenyans, yet the weak public services are still being privatised.

So we can no longer hold onto the Jaramogi-Raila ideal that our lives can improve only after we have more diverse ethnic representation in the top political office. The one thing that must remain is that the government must be accountable to the people. Armed with the constitution, Kenyans have made great strides in this endeavor, and we must not let politicians fool us into abandoning our struggle in the name of cutting down spending and reforming power sharing.

Most of all, the political class must realise that there is a new generation in Kenya. We have abandoned the naivete of the Nkrumah doctrine and have started to put a face to Western capital and ask what havoc it is wrecking in this Kenya. We now realise that referendums and elections cannot address our issues when the billionaires and their Western friends have the money to rig elections, compromise the electoral bodies and pay Cambridge Analytica millions of dollars to misinform and distract Kenyans from the real issues. So we don’t want an economic conversation after we’ve tinkered, yet again, with political succession problems. We want an economic conversation now.

During the Cold War, it was less easy to see the love affair between black Kenyan elites and white capital. The educated Kenyans were few and a majority of them were working for government. The population was smaller, and the government was funding social services in places where the educated Kenyans raised their kids. Also, the threat of Communism in the East and the strong welfare states in the West meant that the World Bank and the United States were more sympathetic to our government funding education and healthcare. But with the neoliberal turn and the fall of the USSR, Western governments no longer felt the same.

So as the World Bank reduced funding for social services, kids like me, with educated parents, started to see that our economic fortunes were worse than theirs. We can’t afford the same social services our parents afforded at our age. In addition, social media has enabled us to get live updates on the social struggles all over the world. We not only see Donald Trump, but also Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. We not only see Theresa May; we also follow Jeremy Corbyn. We listen to the conversations of people like Chris Hedges, Tariq Ali and Yanis Varoufakis. Some of us have studied in the US and have been raised by Pan-Africanists. We don’t just hear about Frantz Fanon, Julius Nyerere, Thomas Sankara, Malcolm X, Angela Davis and James H. Cone. Now we also read them.

So we now see the face of capital more clearly than our parents did. And the more we ask questions about why our money doesn’t stretch as far, the more we see that the poor are worse off than us.

So we are not the generation of 1974 or 2008. We are no longer people who believe that our economic and social problems will be solved through mere political reshuffling without a conversation about the economy. We know that the problem is that white capital still runs this country and that our old school politicians want a referendum to make themselves, not us, comfortable. We know that a referendum will simply waste money on campaigns and popularity contests, the same money that politicians now say that we waste on counties and MPs. And in the end, the referendum will leave the logic of the market, driven by foreigners, very much intact.

What we need is economic reform. We want a government whose pillar of development is WE THE PEOPLE, because we Kenyans are talented, resourceful and simply awesome. We don’t want to hear more of foreign investors and tourists when we want to put our minds and muscles to work. We need the toxic relationship between the state and capital to end. Title deeds should no longer be used as loan security. We want a country that believes in us Africans and that will give us loans because they know we can do the work and succeed. If one does not use land, let them give it back to the public and the public will find someone who will use it. You should not be able to sell land, because you did not make it.

What we need is economic reform. We want a government whose pillar of development is WE THE PEOPLE, because we Kenyans are talented, resourceful and simply awesome.

We want an education that makes Kenyans proud to be human and African, and that encourages them to be creative.

We want universal healthcare because our people deserve to be healthy and live in dignity. That way, our people will also not be afraid to try new ideas because they will not be worrying about healthcare for mothers and kids.

We want a tourism industry that appreciates that the best tourists are WE Kenyans. The communities living alongside wildlife can offer us their homes, build hotels and take care of wildlife better than any foreign “conservationist” who inherited land from King George V.

The push for a referendum instead of economic reforms comes from a fundamental flaw in the Jaramogi doctrine: the belief in indigenous capital as the main economic driver and that we need ethnic diversity in the top 1% of this nation to gain economic justice. And that we cannot get ethnically diverse capitalism before we get political reforms. This naive Jaramogi-Raila belief in indigenous capitalism forgets that capitalism is fundamentally designed to be ethnically exclusive, and ultimately racist.

We still honour Jaramogi for opening our eyes to the complicity of the Kenyattas in economic injustice. And we honour Raila for accepting to be the face of the spirited fight of the Kenyan people against the feudal, capitalist and Western-dominated arrangement that we call independence. However, one thing is clear from Raila’s political career: he’s not willing to extend his challenge to the status quo to the economic realm. That is why he gave up on the most legitimacy he ever had – the people’s presidency – as well as the economic boycott that was our best weapon to challenge Kenyatta’s and Western capital’s hold on Kenya.

The push for a referendum instead of economic reforms comes from a fundamental flaw in the Jaramogi doctrine: the belief in indigenous capital as the main economic driver and that we need ethnic diversity in the top 1% of this nation to gain economic justice. And that we cannot get ethnically diverse capitalism before we get political reforms. This naive Jaramogi-Raila belief in indigenous capitalism forgets that capitalism is fundamentally designed to be ethnically exclusive, and ultimately racist.

We are a new generation. We have tasted the promise of the constitution in putting the people of Kenya at the steering wheel of our own destiny. We are not willing to destabilise the constitution and with it, the framework for public involvement at the counties through devolution, and the demand for public participation in national policy-making. We believe that we can have, and need to have, economic reforms before constitutional change. Most of all, we do not believe that freedom can ever be too expensive.

So we are not seeking first the political kingdom on its own; we are seeking the political kingdom through the economic one. Once we cut down the economic stranglehold of the elites on the economy, we will get closer to a reality where a girl from Turkana or a boy from Kwale, through sheer will power, hard work and social support from an educated nation that is able to see through the ethnic and racist lies, can grow up to become the president of Kenya.