Sudden death on a sunny afternoon

In the early afternoon of Thursday, September 20th 2018, people congregated at the tiny port of Ukara Island on the shores of Lake Victoria, waiting for the arrival of the MV Nyerere, a small ferry bringing passengers and cargo from nearby Bugolola Island. It was a sunny day, with a refreshing breeze blowing off the calm lake. As the 100-capacity ferry approached the jetty, passengers gathered on deck to wave to their relatives. Suddenly MV Nyerere made an abrupt turn to align with the jetty. With so many passengers congregating on one side of the boat, it keeled over wildly, righted itself, and capsized on the other side, throwing dozens of passengers – none of whom were wearing a life jacket – into the lake. Over 200 people drowned, most of them trapped inside the upturned hull. Thirty-eight people were rescued by small boats. The exact number of the dead remains unknown, since the passenger manifest went down with the ship, or so we are told.

Within hours, the BBC World Service was broadcasting the shocking news around the globe. Tanzanian President John Magufuli declared four days of national mourning, and condolences came streaming in from near and far. Presidents Paul Kagame and Uhuru Kenyatta sent their messages of solidarity to Tanzania’s mourning president and citizens. President Shein of Zanzibar “called for calm from those touched by the news, especially when mourning…”CCM Secretary General Ally Bashiru urged people to “continue praying for the survivors and rescue teams and the authorities responsible for ensuring all bodies are recovered.”

Within hours, the BBC World Service was broadcasting the shocking news around the globe. Tanzanian President John Magufuli declared four days of national mourning, and condolences came streaming in from near and far.

President Magufuli then directed the relevant authorities to announce tenders for a new ferry with a capacity of 200 passengers, twice that of MV Nyerere. The government formed a seven-member investigative team led by a former army general to establish the cause of the disaster. Subsequently, Magufuli dissolved the board of directors of the Tanzania Electrical, Mechanical and Electronics Services Agency (TEMESA), which runs ferry services on Tanzania’s mainland, as well as the board of the country’s transport regulator, the Surface and Marine Transport Regulatory Authority (SUMATRA). At the time of writing, no arrests have been made among those directly responsible for running the ferry.

Less than two weeks earlier, on September 14th, the Member of Parliament for Ukerewe District, Joseph Mkundi (Chadema), complained in the National Assembly that he had repeatedly warned the government that the MV Nyerere was “malfunctioning” and in urgent need of repair. A government spokesperson claimed that new engines had been fitted quite recently. The day after the disaster, the Minister of Home Affairs, Kangi Lugola, warned people to desist from spreading false information that might cause turmoil in the country. President Magufuli cautioned politicians about taking advantage of the situation to gain political mileage and cheap publicity. Prime Minister Kassim Majaliwa said the government had started to take steps to bring the lives of the residents in the area back to normal. Cash payments were being made to bereaved families to take the corpses of their dead home for burial. Many could not take the already decomposing bodies of their loved ones home, so many bodies were summarily buried near the lake’s shore, including those of unknown and unclaimed people.

Why boats sink

There are two reasons why civilian passenger and cargo ships sink and people die: natural disasters and human error. Many ships sink when they run into bad weather, high winds, and heavy seas. In other cases, human errors are the main cause. Here are a few examples of maritime disasters attributed to human error rather than purely natural causes.

The sinking of the MV Spice Islander I in 2011 was the sixth largest peacetime maritime disaster ever recorded, with more deaths than the Titanic, the most famous sea disaster of all time. (It appears that the Titanic was speeding in order to reach New York to put out a fire that had been burning in a coal bunker in part of the ship since it had left Southampton.) Thousands of deaths on small boats and canoes go unrecorded, although in total they probably outnumber the tragedies discussed here. (Artisanal fishers also die in considerable numbers.) A thousand minor catastrophes, each resulting in a few deaths, are not worth one big one even if many more lives are lost in aggregate.

The human errors involved in mega-disasters include collisions, running aground, fires and explosions, and capsizing due to structural defects and overloading. Many people drown because they don’t know how to swim and there are no life jackets. If boats are unstable (the MV Bukoba is said to have had a permanent list to one side) then regularly overloading them is likely sooner or later to lead to disaster.

The Kenyan and Tanzanian tragedies listed causing between 2,000 and 2,200 deaths were the result of reckless overloading. For example, the MV Bukoba’s manifest showed 443 first and second class passengers but there was no manifest for third class passengers. At least 800 people died. In the case of the MV Nyerere there is no manifest, so the degree of overloading (passengers and cargo) is not known. One estimate is that about 400 passengers were packed on board, 300 more than the official carrying capacity. With room for an additional three motor vehicles, the ship was also carrying a truck loaded with cement.

The Kenyan and Tanzanian catastrophes were the result of enormous overloading – a consequence of state monopolies that provide inadequate, inefficient and lethal services. To reduce the likelihood of such tragedies recurring, and in the interest of natural justice, it is essential that those responsible be held to account.

Why are boats so overloaded?

Why were these boats so overloaded? Clearly there’s a serious mismatch between supply and demand for passenger and cargo services if the ferries plying our seas and lakes can be so vastly overloaded. Why is there such a mismatch between supply and demand? Because our governments choose to run these services as state monopolies rather than allowing private companies to compete for the trade. What’s the explanation for this? After all, our governments no longer try to run inter-city buses or trucks. A small ferry is a marine matatu. There is already a private ferry plying between Dar es Salaam and Zanzibar. A previous attempt to bring privately-owned ferries to Lake Victoria was frustrated by bureaucracy and politics. Why does President Magufuli jump the gun by announcing a tender for a new ferry? A 200-passenger capacity ferry will merely allow a doubling of the overload factor. Private investors would fall over themselves to provide these basic transport services. Why put additional pressure on the Tanzanian budget, which is already seriously overstretched financing new infrastructure projects such as the Standard Gauge Railway and new aircraft for Air Tanzania?

So who do we hold responsible?

Consciously or otherwise, most commentaries miss the point when attributing blame for such disasters. Rather than focus on the culpability of those endangering lives by overloading vessels, they lament the lack of life boats or life jackets, untrained navigators, inadequate maintenance and so on. An editorial in the East African mentioned the lack of search and rescue services and a “robust system” to control overloading. The elementary starting point—that government agencies perform all the roles that affect the safety of passengers, and therefore share full responsibility for disasters when they happen—is carefully avoided.

The Kenyan and Tanzanian catastrophes were the result of enormous overloading – a consequence of state monopolies that provide inadequate, inefficient and lethal services. To reduce the likelihood of such tragedies recurring, and in the interest of natural justice, it is essential that those responsible be held to account.

So who should we hold responsible? In the Kenyan and Tanzanian cases, government agencies perform ownership, management and regulatory functions. (We may rule out the Lake Victoria Basin Authority, an agency under the East African Community, as a key actor, although it has a national mandate on security issues.) To date, none of the tragedies listed above have led to prosecutions or punishment of those responsible. Given President Magufuli’s ongoing crusade against corruption and waste in government, we can hope that this time will be different. But as justice has never been done in the past, why should we expect things to be different now? If no sanctions are brought against those responsible for these major disasters, there is no reason for them to clean up their act. Very few senior officials are ever jailed for such crimes in Tanzania.

If MV Nyerere had been privately-owned and run, you can be pretty sure that Prime Minister Majaliwa would not be talking about life “getting back to normal”: more likely he and President Magufuli would be “demanding justice”, and arrests, not just sackings, would have already taken place.

Here’s how Koreans dealt with their tragedy in 2014, when over 300 passengers, mostly school children, died in the MV Sewol ferry disaster. The ferry was privately owned and managed.

The Korean way with a ferry disaster

On 16 April 2014, the MV Sewol sank with the loss of 304 passengers and crew. The sinking resulted in widespread social and political outrage within South Korea, directed at the government of President Park. In class actions, bereaved families sued the government and ferry owners. The ferry was carrying more than double the ship’s passenger limit. In November 2014, the captain of MV Sewol was acquitted of murder but sentenced to 36 years in prison while the eleven other crew members were indicted for abandoning the ship. The company’s CEO was charged with “causing death by negligence”. The owner of the ferry later committed suicide. In July 2018, a Seoul Court ordered that every family receive USD175,000 for each victim, and additional compensation of up to USD70,000 for each family member. The bereaved continue to sue the owners of the ferry.

What does this sad story teach us? First, that private ferry owner-operators in South Korea are also capable of bending the rules and overloading their vessels for profit, with fatal results. But second, public outrage is not only permitted but is directed at the government as much as the boat owner, for failure to enforce safety regulations or rescue more passengers. (Three years later, mass demonstrations over grand corruption scandals led to the ouster of President Park Geun-hye, who is now in jail.) Lesson: Those responsible for the disaster were quickly identified, prosecuted and punished. Why should the bereaved in the MV Nyerere case not blame – and sue – the government officials responsible for the death of their loved ones?

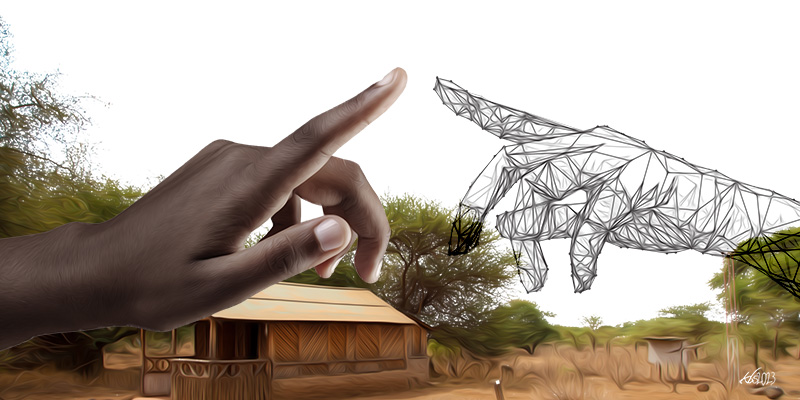

The Nile perch in the room

If the majority of the passengers on board the MV Nyerere were not listed on the ship’s manifest, it is highly likely that the fares they paid for their final voyage also went unrecorded. A simple task for the commission of inquiry will be to examine past manifests and accounts of the MV Nyerere to establish what proportion of income was reported officially and how much was “privatised”. (This question was not asked when the MV Bukoba sank more than 22 years ago, but at the time it was widely believed that unrecorded passengers and freight generated considerable rents that fed a food-chain stretching from Mwanza to Dar es Salaam.) Rent-seeking alone would explain official reluctance to privatise lake transport services in the interest of ordinary citizens.

If the majority of the passengers on board the MV Nyerere were not listed on the ship’s manifest, it is highly likely that the fares they paid for their final voyage also went unrecorded. A simple task for the commission of inquiry will be to examine past manifests and accounts of the MV Nyerere to establish what proportion of income was reported officially and how much was “privatised”.

In sum, running commercial ferries on Lake Victoria or anywhere else should not be a state monopoly. Neither should it be a private monopoly, or cartel, but rather a lively competitive market with multiple players and properly enforced regulations that balance the legitimate search for a fair profit with the fundamental imperative of assuring passengers’ safety. Unfortunately, the relationship between the state and the private sector in Tanzania and Kenya rarely allows for transparent economic regulation that is not motivated by collusive deal-making involving elements of both bribery and extortion. Lakeside people will continue to risk their lives on a daily basis until this fundamental constraint is addressed.