Thirty-six years ago, in 1982, the year Bobi Wine was born, Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni was busy commanding the war that eventually led him to power. At 36, Museveni had run for president in 1980 as a rabble-rouser representing the new Uganda Patriotic Movement (UPM).

His party did not even stand an outside chance of winning the election, with Milton Obote’s Uganda People’s Congress (UPC) and Paul Ssemogerere’s Democratic Party (DP) being the hot favourites. In the end, Museveni even failed to win his own parliamentary seat. During the campaigns, he had warned that he would start a war should the election be rigged, and he did indeed start a war after UPC controversially claimed the election for itself amidst claims that DP had won.

Paulo Muwanga, who was the head of the interim Military Commission government on which Museveni served as Deputy Minister for Defence, had arrogated himself the powers that were entrusted in the Electoral Commission to announce election results, returning UPC as the winner, with Obote proceeding to form a government for the second time, having been earlier deposed by Idi Amin in 1971.

Museveni had watched the intrigue and power play and how the gun had emerged as the decisive factor in Ugandan politics since 1966. He had decided early in life that his route to power would be through the barrel of the gun. His determination to employ the gun became manifest when he launched a war against Amin’s new government in the early 1970s.

Museveni’s Fronasa fighters were part of the combined force that was backed by the Tanzanian army to flush out Amin in 1979. Also among the fighting forces was a group that was loyal to Obote. Museveni’s and Obote’s forces and other groups were looking for ways to outsmart one another as they fought the war. It was a time when Bobi Wine was not yet born.

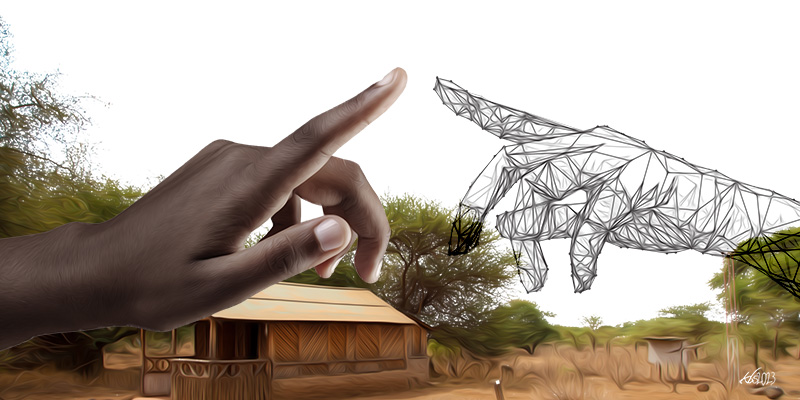

Bobi Wine (real name Robert Kyagulanyi), who has been a Member of Parliament for just a year, has followed a different path. He is one of those Ugandans who believe that Museveni should be the last Ugandan leader to access power through the barrel of the gun. He wants future leaders to work their way into the hearts of Ugandans and convince them that they can take the country forward.

Bobi Wine first rose to popularity through music. Even though the popstar is new to Ugandan politics, he has for over a decade been disseminating political messages through his songs, in which he positions himself as a poor man’s freedom fighter.

Bobi Wine (real name Robert Kyagulanyi), who has been a Member of Parliament for just a year, has followed a different path. He is one of those Ugandans who believe that Museveni should be the last Ugandan leader to access power through the barrel of the gun.

Through his music, he has criticised the government when he felt it sold the people short; he has castigated the Kampala City authorities over throwing vendors and other poor people off the streets; and he has sought to encourage Ugandans, especially the youth, to take charge of their destiny.

“When freedom of expression becomes the target of oppression,” Bobi Wine said in one of his songs, “opposition becomes our position.” That was before he joined active politics.

When he married in 2011, he made sure that the marriage was celebrated by the Archbishop of the Catholic Church in the capital. When he was incarcerated recently, there were prayers for him at Rubaga Cathedral, the seat of the Catholic Church in Uganda. Catholics are the biggest religious grouping in the country.

Bobi Wine was born in Gomba, one of the counties of Buganda, the biggest ethnic group in Uganda. He has worked his way into the Buganda king’s heart, dubbing himself “Omubanda wa Kabaka” (the King’s Rasta man).

In Uganda’s music industry, Bobi Wine and his “Fire Base Crew” rose to the very top in their category, with Bobi Wine calling himself the “Ghetto President”, whose retinue included a “Vice President”, a cabinet and other members. He also has a security detail. His chief personal bodyguard – Eddie Sebuufu, aka Eddie Mutwe – was picked up at night by suspected military operatives on August 24, 2018.

Bobi Wine has over the past decade traversed the country where he has been performing as an artiste. Then, shortly after his election to Parliament, he travelled to many places within the country to introduce himself this time as a politician. He enjoys name recognition across the country that no Ugandan politician of his age and experience can command.

Battle for the youth

Bobi Wine plays the music that many Ugandan youth want to listen to, but he also preaches the gospel of change and prosperity in a way that is attracting crowds to him. He was born in rural central Uganda but he moved into a shanty neighbourhood of Kampala early in life, struggling through what most young people in the city experience. Although he went school up to university level, he went through all the hassles that young Ugandans go through. He speaks their language.

The Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) projects that at the mid-point of this year, Uganda had 39,041,200 people. Of these, only 648,000 people were projected to be 70-years-old or older. This means that Museveni, at 74 years of age, is among a lucky 1.7 per cent of Ugandans who are alive at the age of 70 or above. In fact, only 450,500 people, or 1.2 per cent of Ugandans, according to the UBOS projection, are as old as Museveni or older.

Reliable numbers on employment in Uganda are hard to come by but it is generally agreed that the country has one of the highest youth unemployment rates in the world. Museveni’s opponents often cite his age to make the point to the youth that their future is not safe with a 74-year-old leader who has been in power for 32 years.

The Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) projects that at the mid-point of this year, Uganda had 39,041,200 people. Of these, only 648,000 people were projected to be 70-years-old or older. This means that Museveni, at 74 years of age, is among a lucky 1.7 per cent of Ugandans who are alive at the age of 70 or above.

Museveni being Museveni – the Maradona of Uganda’s politics – has tried to tilt the debate on age to his advantage. He has, for instance, distinguished between “biological age” and “ideological age”, saying that many Ugandans are young biologically but very old ideologically. He has identified “ideological disorientation” as one of Uganda’s “strategic bottlenecks”, positioning his “ideological youth” as the solution. For one to be “ideologically young”, Museveni says, one needs to have the right ideas and mindset on how to transform society. He regards himself as a master in that. He says biological age is of no consequence in politics.

In his State of the Nation address last year, the Ugandan president said staying in power for long – and therefore being old – is a good thing because the leader gains immense experience along the way. In the wake of the recent arrest of Bobi Wine and 32 others who were charged with treason after allegations of stoning the president’s motorcade, Museveni wrote at least six messages on social media addressed to “fellow countrymen, countrywomen and bazzukulu (grandchildren)”. He now takes comfort in addressing many of his voters and opponents as grandchildren.

The choice of social media (especially Facebook and Twitter) as the preferred way of transmitting the president’s messages also raised debate. From July 1, social media users had a daily tax imposed on them because the president said people used the platforms for rumour-mongering. Many social media users have avoided the tax by installing virtual private networks (VPNs) on their handsets and so the “rumour-mongering” on social media continues. Since younger people spend a lot of time on social media, their septuagenarian president has decided to follow them there. Whenever he has addressed them as “grandchildren”, there have been hilarious responses in the comments section.

Beyond the debates, Museveni has in past election campaigns come up with a number of things to attract the youth, including recording something akin to a rap song in the lead-up the 2011 elections. But if it is about music, Museveni now faces Bobi Wine, a man less than half his age who has spent all his adult life as a popular musician.

Museveni’s government has tried one thing after another in an attempt to provide the jobs that young people badly need, with initiatives ranging from setting up a heavily financed, but highly ineffectual, youth fund in the ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development. After the 2016 elections, in which Museveni suffered the heaviest defeat in Kampala City and its environs, he set out to dish out cash to youth groups to promote their businesses. Not much has come out of this initiative.

When he shot to power in 1986, Museveni rebuked leaders who overstayed their welcome, saying that the vice was at the root of Africa’s problems. As time went by, and with him still in power, he changed his views. He now says that he actually prefers leaders who stay in power for long periods. Museveni’s opponents latch onto such contradictions as they keep piling up.

Is it Bobi Wine’s turn?

Over the last 32 years that he has been around, Museveni has had a number of challengers and Bobi Wine is now threatening to storm the stage as the new kid on the block.

When he shot to power in 1986, Museveni rebuked leaders who overstayed their welcome, saying that the vice was at the root of Africa’s problems. As time went by, and with him still in power, he changed his views. He now says that he actually prefers leaders who stay in power for long periods.

Many of the people who were in the trenches with Museveni in the earlier years and who dreamt of picking the baton of leadership from him have dropped their ambitions because age and/or other circumstances have come into play as Museveni stayed put. Former ministers who once nursed presidential ambitions, like Bidandi Ssali, Amanya Mushega, Prof George Kanyeihamba and even the younger Mike Mukula, for instance, have since retreated to private lives. Others, like Eriya Kategaya and James Wapakhabulo, have passed on.

Of the Bush War comrades who harboured ambitions of taking over from Museveni, only four-time challenger Kizza Besigye and former army commander Mugisha Muntu remain standing, with the largely silent former prime minister Amama Mbabazi thought to be lying in wait for a possible opening.

By staying in power for so long – since January 1986 – Museveni has worn out his ambitious former comrades and perhaps even ensured that the chance to rule the country passes their generation by, a reality that has made it more likely that he will face a challenger who is younger than his own children.

But Museveni will not allow this generation of youth to win. The ruling party consistently stifles the emergence of younger leaders. In the lead-up to the 2016 election, for instance, Museveni’s National Resistance Movement party saw a rare surge in activity championed by younger people. One of Museveni’s in-laws, Odrek Rwabwogo, was among them. Rwabwogo had resorted to penning a string of articles in the partly state-owned New Vision newspaper about how the ruling party’s ideology could be sharpened to take care of the new Uganda. A number of other younger leaders within the party vied for space and expressed their visions in what was interpreted by some as a jostle for a front row seat as Museveni was expected to be standing for his last term in preparation for retirement in 2021.

Then, shortly after returning to power in 2016, Museveni engineered the removal from the Constitution the 75-year cap for presidential candidates, which would make him eligible to run again for as many times as he would be physically able to handle. This was a sure sign that Museveni was not willing to hand over power to a more youthful generation.

Repression heightens

The move to remove the age limit for presidential candidates from the Constitution inevitably invited stiff opposition from those who for decades have worked towards removing Museveni from power. In September last year, army men invaded Parliament and beat up and arrested Members of Parliament who were trying to filibuster the debate and perhaps derail the introduction of the bill to remove the age limit. Two MPs were beaten to a pulp and one of them, Betty Nambooze, has been in and out of hospitals in Kampala and India over broken or dislocated discs in her back.

This unfortunate incident, however, did not stop the State from bringing charges against her when after the shooting to death in June of an MP, Ibrahim Abiriga – who was one of the keenest supporters of the removal of age limits – Nambooze made comments on social media that the State interpreted as illegal. This week she had to report to the police over the matter, but she was informed that the officers were ready to have her charged in court, where she was delivered in an ambulance. She was carted into the courtroom on a wheelchair for the charges to be read out to her before the magistrate granted her bail. She sobbed all the way and afterwards wrote on Facebook that while in court she was “crying for my country”.

Francis Zaake, the other MP who was also was beaten, had to be taken to the US for treatment. He is now being treated again and is set to be fly out of the country due to injuries he sustained during the violence in Arua in which Bobi Wine was also attacked by soldiers of the Special Forces Command that guards the president.

Bobi Wine and 32 others have since been charged with treason but Zaake hasn’t yet – though Museveni has said in one of his statements posted on social media that Zaake escaped from police custody. When he is supposed to have escaped, Zaake was unconscious and could not move or talk. He was reportedly just dropped and dumped at the hospital by unidentified people. The head of the hospital has said that Zaake is at risk of permanent disability because of the damage he suffered to his spinal cord. The authorities say they are waiting for Zaake to recuperate so that he can face charges related to the violence in Arua.

By these callous actions, Museveni has demonstrated how ruthless he can get when his power is challenged. He has referred to the injured MPs as “indisciplined” and has not extended any sympathy towards them.

Those who have dared to challenge Museveni, especially Besigye, have been here before. The new opposition politicians currently in the line of fire, including Bobi Wine, have been served with a dose of what to expect if they push Museveni hard. The decision on how far they are willing to go is now in their court.

It seems that Museveni plans to apply to Bobi Wine the script he has used on Besigye over the past two decades. Apart from being targeted for physical assaults, Bobi Wine will be – and it is already happening – isolated from members of his inner circle, especially those who provide him with physical cover. They will be arrested, intimidated, or offered money to start businesses, a ploy to get them to abandon him. Some, like his driver Yasin Kawuma, who was buried a few weeks ago, will die.

It seems that Museveni plans to apply to Bobi Wine the script he has used on Besigye over the past two decades. Apart from being targeted for physical assaults, Bobi Wine will be – and it is already happening – isolated from members of his inner circle, especially those who provide him with physical cover.

Another thing the Museveni machine will do, and which it has done in the past, is plant fifth columnists around him – men and women who will show immense eagerness to work with Bobi Wine to remove Museveni from power but whose real assignment will be to get him to make mistakes and to spy on him.

It is also to be expected that Museveni will reach out to Bobi Wine with some kind of deal – he seems to offer all his credible opponents proposals for an amicable settlement so that they can drop their political ambitions. It is hard to say whether Museveni has already approached Bobi Wine or not, but there are rumours to that effect.

Ultimately, it will be up to Bobi Wine to decide what he wants to do going forward, but with him fighting for his life in hospital, we dare not predict the future.