There are three main concerns Kenyans from all walks of life have during illness or any manner of health crisis: 1) Who is going to take care of me, and where do I have to go to access that care? 2) Will all the options I need for full care be available to me, and are they the best ones there are? 3) Who is going to pay for the options I take? Is it going to have to be me, and what does that mean for my budget and my life?

These are obviously very valid and important questions, and it is a challenge to separate them because they weave so intractably into each other. Where we go and who we see when ill are dictated by who we are. Our age, gender, religion, socio-economic class, employment status, tribe, and proximity to an urban area or hub dictate the options available, and all these rest on the bedrock of the available funds to create and maintain a system of administration, equipment and skilled workers that avail healthcare services. All that considered, let us unpack each of these questions to see much more clearly where we sit in this often confusing and scary place.

Becoming a patient

The first thing we need to remember is that nobody plans for illness, and in that African cultural and spiritual way, we actively assume full wellness in anyone until they are on the verge of collapse. This is rooted in a commonly understood and yet completely unsaid superstition that if we summon illness it will come to stay; so we deny it until we cannot any longer. Kenyans are much less likely to be hypochondriacs than they are to sit uncomfortably on a symptom until it is alarmingly close to its worst possible manifestations.

The first thing we need to remember is that nobody plans for illness, and in that African cultural and spiritual way, we actively assume full wellness in anyone until they are on the verge of collapse. This is rooted in a commonly understood and yet completely unsaid superstition that if we summon illness it will come to stay; so we deny it until we cannot any longer.

A lot of this is linked to the roles we play in society: many people have hostile employers who view illness as a way to chicken out of work. Additionally, there are things we cannot opt out of, even while ill: parenting, especially by mothers of small children, is an example of a 24-hour shift regardless of our state of health. Many doctors will actually make a decision to admit and keep a mother who needs bed rest in hospital because sending her back home is a guarantee that nobody will let her stay in bed longer than five minutes. Many mothers cannot even have a short call in peace when in a house with a small and active child, let alone have a quiet meal or a full night’s sleep.

The idea of who is going to take care of a sick person, therefore, has to begin with who is available to take over or cover for the tasks they have, because this helps them on the path to acknowledging lack of wellness that is severe enough to need intervention from an outside source. Women again tend to draw the short straw and take on a third shift of minder to the sick and frail in a household. Predictably, another woman will likely be destabilised from other roles to come and hold fort for a woman if she herself is sick. Women therefore end up trading their time (as it is seen as less valuable) to take sick relatives to hospital and to assist recuperation there and at home.

Where we go to find help

When seeking help for illness, we prefer to play our cards as close to our chests as possible, and as Kenyans we cannot really blame ourselves for this. In a society where trust metrics have been in active decline for a while now, we are used to being scammed. We watch liars every day on our news channels and listen to them every Sunday at church. Choosing the devils we know, however inefficient they may be, is an easier option emotionally for a people weary of untruths.

One option is to go straight to a chemist, because most people end up at one, one way or another, to buy medicine. They relay the group of symptoms to the person behind the counter, whose only claim to care is a white coat. This person listens to the symptom list: to be fair, it is usually pain, stomach problems, or something respiratory, the majority of which are not too serious, and these things can mostly be managed over the counter. There is definitely room for one-stop interventions and medications, but one key issue is that a single quick public exchange often reduces the quality of the questions and the depth of the answers given. It is thus very easy to miss the subtle nuances between a series of self-limiting symptoms which need instant calming for quick relief, and an unfolding disease process which would need a more intensive treatment plan, as mapped out by lab and image investigations.

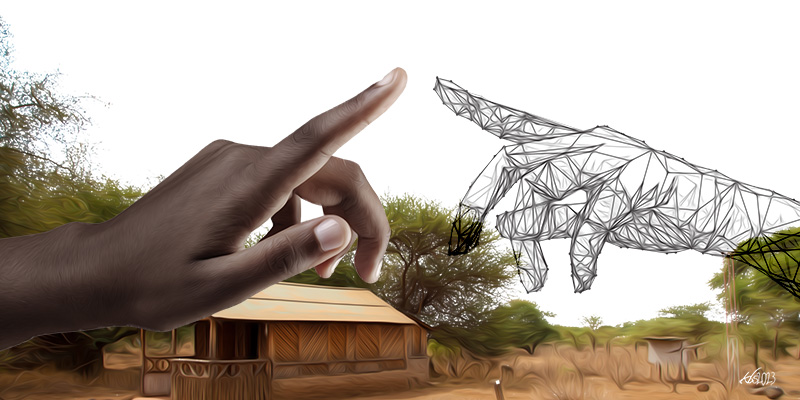

Another key locus in an honest healthcare analysis in Kenya is the traditional practitioner, who can be a herbalist, spiritualist, medium or even a medicine man or woman. Often the holders of cultural knowledge and trust, and able to speak to us deeply in language we can understand, using a frame of reference we are instantly familiar with, they have often been much more affordable and much easier to access, sparing us the long queues on hard chairs which end with cold, uniformed people using hard words that nobody understands.

Traditional practitioners can also seamlessly weave in spiritual ideology around healing, which can be a challenge for Western-trained caregivers. Several schools of thought would seek to corral or erase the traditional practitioner, but if anything, they are becoming increasingly popular in light of the limits current care has in seeing the person as a whole being as opposed to a concatenation of symptoms that need solving. Additionally, with the rise of Eastern practices, we are seeing more of Chinese medicine and Ayurvedic methods being explored in academic spaces. A reasonable strategist can project that the diverse African healthcare methods are the next frontier for Big Pharma. This is a conversation that is going on globally, not just in Kenya, and we would do well to take the brief headstart we have to explore some of these areas to whatever advantage we can.

The list of formal facilities available to Kenyans includes public hospitals, clinics and dispensaries, known mostly for understaffing, overcrowding, and subsequent inefficiency. Though many Kenyans go in and out of them daily without too many issues, they boast few stories of consistently stellar service. Faith-based and mission spaces have had many successes, but the vast majority of them are small operations and the footprint of their impact, even cumulatively, is thus limited. Private facilities close out the ranks; they are known for better quality amenities and offerings, but with the price tag we have learned to expect from all private suppliers of goods that should be publicly available—including transport, education and security. They are mitigated by market forces alone, and not subsidised by our taxes or regulated by public policy.

The list of formal facilities available to Kenyans includes public hospitals, clinics and dispensaries, known mostly for understaffing, overcrowding, and subsequent inefficiency. Though many Kenyans go in and out of them daily without too many issues, they boast few stories of consistently stellar service.

The case against being “world class”

We should really worry about the concept of “world class” as an abstract standard permeating our ideas of what good quality should be, especially with a sector as vast as healthcare. First of all, the idea of urbanness and urban contexts is intractably tied to the availability of specialist caregivers and facilities all over the world. Attracting and keeping certain cadres of healthcare providers necessitates certain amenities and access to a lifestyle associated with upward social mobility. However, rural contexts have human beings who are just as much in need of these exact services, but “world class” escapes an association with village life and small scale. There is nothing inclusive about it. It is not a term that was designed to make room for people who fall outside its reach.

Secondly, the trappings of “world class” care are almost, blow by blow, things that can be associated with luxury and availability of high budgets to afford the comforts over and above the basics. In the mostly capitalist context of the Kenyan economy, dignity is one of those things, because in many senses people have to pay to matter. The speed at which people will rush to the bedside of a VIP will tell you that even though the value system of care argues that all people are equal, the Orwellian situation where some are more equal than others, as detailed in the classic literary work Animal Farm, can most often be trusted to prevail. A “world class” situation where people who pay and people who don’t pay are getting the same quality of service can create conflicts, and we therefore find that we have to create discomfort for people who pay less in order to justify the comfort of those who are paying more. A practical example of that is the ever-shrinking size of economy class seats in most airliners.

Thirdly, “world class” in resource-limited contexts like these has tended to focus, rather dangerously, on flashiness of equipment and an array of available specialties, rather than on how the people feel about how they are being treated and guided on the path back to health. We have seen billboards with photos of futuristic diagnostic machines, but heard horrifying stories of patients suffering in the same hospitals where the sci-fi imagers sit. In many ways, we like the idea of a hospital that looks like one abroad but haven’t thought beyond that to a hospital where Kenyans are treated as though they matter.

But even as regards care, we must focus on the caregivers, and the situation with them in this country has been tenuous for a while. The line between public healthcare workers and private ones is very thin because most of them receive their education in the same institutions. The labour issues of the healthcare sector have been known for a while, with strikes rocking the nation at different points, causing unfathomable gaps in direct patient care and public health interventions for vulnerable populations, such as children under the age of 5, people living with HIV, pregnant mothers, the elderly etc. For many reasons, top among which are understaffing, overwork and underpayment, many caregivers are burned out and unable to engage humanely in the lives of their patients, and this humane engagement is the bedrock of what the intention of the word “care” is. Professor David Ndetei et al published a preliminary sample study in 2014 that found that over 95 percent of caregivers at Kenyatta Hospital, Kenya’s largest teaching and referral hospital, were showing clinical signs of burnout. As such, we can have all the best machines in the world, but if we do not also ensure that our caregivers are at their best, we are already running a losing race. The same can be said of healthcare support and administrative staff.

A fourth element of “world class”, which we may have been phased out due to unfocused policy, is matching the disease burden and health needs of the people with the opportunities for training new specialists. This country is only just coming to terms with its prevalence of cancer and many non-communicable diseases, for instance. Our previous leaning on tropical medicine and infectious diseases without keeping a sharp eye on the peripheries has allowed this to feel like it snuck up on us when in reality people have always been suffering: it is just us who didn’t take notice.

We can add to this list the conditions that are considered “rare” and therefore possible to ignore because their sufferers have not reached a number large enough to make macroeconomic investment worthwhile. As such, those with the means are able to get treatment and management in other countries which, whether for free market reasons, solid national planning, or both, enabled spaces where this is available. Often we hear of VIPs who manage public resources having the additional perks of opting out of the care available here, which is almost as though, when it is convenient, they get to stop being the Kenyans they are happy for the rest of us to be. This is not an indictment on everyone who has had the privilege of getting on a plane to places like the UK, India or South Africa to access treatment: it is, however, a recognition of the tragedy in the lives we have lost because so many were not able to access the same options. It becomes pricklier when we consider that sometimes there is room for our national public insurer to pay for people to get care abroad, which is obviously wonderful, but why do we remain unable to do what it would take to avail those options here to all Kenyans? How can we ensure that all lives are viewed as equally valuable?

Often we hear of VIPs who manage public resources having the additional perks of opting out of the care available here, which is almost as though, when it is convenient, they get to stop being the Kenyans they are happy for the rest of us to be. This is not an indictment on everyone who has had the privilege of getting on a plane to places like the UK, India or South Africa to access treatment: it is, however, a recognition of the tragedy in the lives we have lost because so many were not able to access the same options.

A general issue with accessing care abroad is that the great equaliser of persons as regards quality of care becomes emergency services. Regardless of who we are, if we are involved in a road traffic accident or suffer some other acute trauma, we are bound to the nearest facility, wherever it may be, to get the interventions that we need in order to make sure that we buy time and avoid death. During such moments, it is not how much we can pay that matters as much as the assurance that wherever we go, the people in both private and public spaces can give us the exact care we need to keep us alive. Currently that is a difficult assurance to give Kenyans, and so these aspirations towards world-class care are more distractions than they are honest analyses of what is actually possible for us.

Who pays for universal healthcare?

The organic segue when discussing value of life in healthcare is to ask ourselves a few rather philosophical questions. How much are states willing to invest in the life and wellbeing of their citizens? A quantification of the amounts of money a nation’s citizens pay out of pocket for healthcare would be one way to understand that. Understanding where citizens have to plug in from their own net income—and why—may be a more qualitative way to map out any gaps in a country’s healthcare spend.

We have to negotiate the practicalities of actively rolling out what we call universal healthcare. It cannot qualify as universal if citizens cannot access it, or if they are paying a significant part of its cost from their own pockets. It bears explaining that once rolled out, Kenyans may not pay for it, but it is far from free: What it means is that everyone’s care is averaged out and charged to each citizen via the varied taxes we already pay, as well as from the net incomes of a nation from the items it offers for sale to the global market. Basically, we put money in Caesar’s pocket, and it is added to whatever Caesar already has coming in, and then Caesar pays for everyone. The reliance on a central source of funds for our healthcare can be worrying if we consider our rising national debt, and our known tendencies to make monies intended for public expenditure disappear. Furthermore, it has been a long time since Kenya even pretended to spend 15% of its total budget on healthcare, as it pledged in the 2001 Abuja Declaration, so how we move from blatant disregard to even just toeing the minimum will be a matter of the ideal sustained political will that is known to elude us on many other matters of public interest.

The other source of money for healthcare spend is medical insurance, and because of the relatively tiny percentage of people who are privately insured in this country, most of whom access this as a benefit of formal employment. Comprehensive comparisons and analyses have also been hard to come by, but it is the rare client who has not been blindsided or left in the financial lurch by the sudden onset of red tape and small print. Additionally, it is notable that the list of exclusions are not a fair reflection of the disease burden of this population: the alarming number of services that women are unable to easily access as part of comprehensive reproductive health are testament to that. By and large, it is understandable that insurance companies would want to keep a tight handle on spending and payouts, especially when having to work with a relatively small number of customers. It has, however, been disappointing that for professionals who are well versed in betting on the macroeconomics of health and profiting off savvy investments, the clear advantages of a demographic youth boom such as Kenya’s has not created a space in which to partner with the state in more scalable ways to make healthcare available for more people.

It is impossible to consider healthcare without considering the effects of harambee, ubuntu or community contributions. Many Kenyans have reaped the benefits of belonging to a culture that values, for many reasons, coming together to help a person in need. The person does not even have to belong directly to our tribe, religion or family: we will sacrificially find coins to help someone who has been visited by the misfortune of an illness whose treatment surpassed their ability to pay.

However, the intervention of the many is suited to a one-time issue which will hopefully go into remission forever. The burdens of a chronic condition can quickly elicit compassion fatigue in even the most charitable people. Additionally, personal finances are finite, especially in shaky economic times, and the same person who could be generous at one moment can find his circumstances changed radically during a subsequent request. Because of the unpredictable nature of misfortune and the opaque nature of healthcare costs, someone can so easily come from contributing to another’s issue only to find himself the next victim of these particular debts that can so easily impoverish. Moreover, healthcare costs are unrelenting: they don’t care whether the person is working (and in the case of some illnesses and conditions, the sufferer’s ability to do so is actually taken away) or able to pay for them; they just continue to rack up. It is a terrible and cruel thing for any person to have to contemplate whether it is fair that they cannot raise the amount of money they need in order to guarantee healing and well-being in this life.

It is impossible to consider healthcare without considering the effects of harambee, ubuntu or community contributions. Many Kenyans have reaped the benefits of belonging to a culture that values, for many reasons, coming together to help a person in need.

Light at the end of the tunnel

Despite the fact that it would be easy for cynicism to set in, there are actually several things to be optimistic about as regards healthcare in this country. First among these is that we can always hope that the seemingly renewed state commitment to health for all can be a multipartisan agenda whose achievement can transcend the short-term possibilities of political gain for a few. We may, for many reasons, actually get the high political will and follow-through with this that would not only make it a success but also be a shining light for the failures in provision of other public goods for Kenyan citizens. The massive strides forward we are seeing in Makueni County, helmed by its determined governor, Kivutha Kibwana, are practical attempts at universal healthcare that redefine it as possible, not merely as an ambitious pipe dream.

Secondly, the labour conflicts in this sector have illuminated and mapped out the gaps faced by the civil servants who work in it. Because of this, we have a much clearer picture when we look at the issues raised by both them and the patients or service consumers about what is wrong, and are thus in a much better position to look for solutions, with the great advantage of a multidimensional approach.

The presence of devolution is a mixed bag. Many argue that the complexities of healthcare service provision meant that Counties were prematurely bequeathed this responsibility, especially without a data-driven approach to truly understanding the direct concerns of each county. Others had hoped that because each county has such distinctly different needs, the room for and success of innovative solutions that have been created by this separation from national overview can outperform the wide blanket of country-wide strategy by far. Again Makueni County’s innovative methods stand out significantly. All agree, however, that we need a much slower, more deliberate plan to tease out the relationship between the state and the county as regards the healthcare for citizens, especially along the lines of who pays for what.

A fourth advantage is the position of Kenya regionally and continentally as a hub for quality and ambition as regards healthcare policy and practice. Kenya’s public sector is known across the continent for its progressive, almost radical HIV care, treatment and prevention policies. Kenya was the second country in Africa and is still among a minority in the world to roll out pre-exposure prophylaxis to the masses and is deeply involved in research and experimentation towards both a cure and a vaccine.

Another example is our no-nonsense approach to maternal mortality, most recently elaborated as the Beyond Zero campaign led by the Country’s First Lady, Margaret Kenyatta. This campaign has been highly praised globally and is being studied to map out how its implementation can be replicated in other spaces. We’re currently debating and drafting legislature on fertility treatment and surrogacy, and despite our societal and religious conservatism, have been able to shift sexual and reproductive health conversations, especially as part of women’s rights, in very significant ways. The private sector has not been left behind; for many of the region’s citizens, Kenya, and Nairobi in particular, are destinations for quality specialist care and access to services that are not available to them at home. There are definitely ethical concerns in turning a country into a medical tourism hub offering services that are not available for the majority of its own citizens. It is, however, a comfort to note that the ingredients for success are already here.

Kenya’s public sector is known across the continent for its progressive, almost radical HIV care, treatment and prevention policies. Kenya was the second country in Africa and is still among a minority in the world to roll out pre-exposure prophylaxis to the masses, and is deeply involved in research and experimentation towards both a cure and a vaccine.

A follow-up to this is the rising numbers of both facilities and care workers in training. Again, we remain aware that tertiary institutions in this country, and the wider education sector, have also had their struggles with labour tensions, privatisation, underemployment and reduced funding from central government, but that is a whole other article. On the bright side regarding health, there are many more training opportunities available, but the vast majority of these are for first certificates, diplomas and degrees. Specialist training programmes for all cadres of healthcare givers are still inordinately expensive, and the government-sponsored opportunities for those have long waiting lists at both national and county levels.

One other place that Kenya has had some tensions is in negotiating the differences in roles between clinical officers, nurse practitioners and doctors. The facts on the ground remain that we still have a dire shortage of primary care interventionists, and our hybrid approach that allows varied cadres to see patients covers a much larger population base than a purist model would. That being said, we could still do with a more iterative, responsive understanding of who is trained to do what, so that patients are very clear about the clinical boundaries of each cadre.

A final point to note (and this list is by no means exhaustive) is that there is a general change in public attitudes to healthcare, the result of the diffuse access to information that has been occasioned by the Internet. There is more education about topics that were previously covered over by a lot of stigma and ignorance: one example is mental health. Because of this, the public has been empowered to ask more questions and demand timely, satisfactory answers from individual care givers, institutions and the sector at large. A part of it is definitely a more entrenched awareness of their rights as citizens as broken down in the Constitution, which is very explicit about the right to health and even specifically, access to emergency care. Citizens are also able to take to social media streets and host online conversations and debates, which have become offline calls for accountability that have been successful in stopping malpractice and neglect. The media are also taking the need for accessible, comprehensive information more seriously, and there has been a significant rise in health-centred human interest stories, and more expert journalists who are able to unpack complex health issues in ways that Kenyans are happy to learn from, engage with, analyse and debate.

There is a lot of room to stick it out and hope for the better—just because so much has been so bad for so long does not invalidate the good things that have been happening under the radar. All said and done, though, we must wait and see if true universal healthcare is possible within the context of what Kenyan healthcare has been and has the potential to be.