The population surge now taking place across sub-Saharan Africa is this continent’s equivalent of the Western post-war Baby Boom. The congruence with demographic transitions elsewhere suggests that in theory, Africa’s “Baby Boomer” millennials are well positioned to affect a radical transformation. The case for a generational social movement intersects Kenya’s potential for a demographic dividend similar to the one underpinning the rapid rise of the Asian Tigers.

Two thousand years ago, Africans comprised an estimated 12 to 15 per cent of the world’s population. Africa’s share had dropped to 9 per cent by 1500 AD. By the end of the 19th century, the export of African slaves to the Americas and environmental calamities contributed to its decline to 6 per cent. Initial conditions, including the continent’s low population densities, physical and spatial barriers to communication, and historical isolation from other world regions, made it vulnerable to European exploitation.

Africa’s population began catching up during the decades of colonial rule, and spiked after independence. The continent’s share of the world’s population reached 17 per cent in 2017, and Africa is projected to host over a quarter of the world’s people by 2050. Naturally, the exceptionally high growth rates of the past several decades pose some formidable developmental challenges for Kenya and for the many other African nations with similar demographics.

Fewer births each year results in a country’s young dependent population decreasing relative to the working-age population. With fewer people to support, a country has a window of opportunity for rapid economic growth, but only if it gets its social and economic policies right. The decline in fertility, albeit slower than was the case in Asia, should exert a similar effect on African countries.

Kenya’s population has been surging since independence, growing from 8 million in 1960 to 13 million in 1975, and doubling to 26 million in 1995. These numbers confirm the fact that all the generations of Kenyans alive today were “Baby Boomers” when they came of age. The result is a population pyramid that over time has more in common with Mt. Kenya than with Mt. Kilimanjaro.

Since the colonial era, Kenya’s lopsided population distribution, where over 80 per cent of the population is concentrated in the 23 per cent of high potential land, has combined with the threat of environmental degradation to provoke Malthusian predictions of impending calamity. During the 1990s, urbanisation and the numbers of new university graduates entering the economy provoked a new set of concerns.

Kenya’s population has been surging since independence, growing from 8 million in 1960 to 13 million in 1975, and doubling to 26 million in 1995. These numbers confirm the fact that all the generations of Kenyans alive today were “Baby Boomers” when they came of age. The result is a population pyramid that over time has more in common with Mt. Kenya than with Mt. Kilimanjaro.

In 1998, I reviewed an internal US State Department analysis of the problem that outlined three future scenarios for Kenya: economic take-off; collapse; and muddling through. Where the document highlighted the prospects for political instability in the future if the then Moi regime of public mismanagement and political corruption were to persist, I opined that Kenyans were a resilient people who would somehow manage as long as the rains were okay.

This proved to be true. The rise in annual GDP growth during the following years may have partially offset the spreading rot, but the large numbers of educated youth entering the work force exposed the unsatisfactory state of affairs, as the accounts of urban millennials published in The Elephant over the last two months have shown.

Demographic dividends and deficits

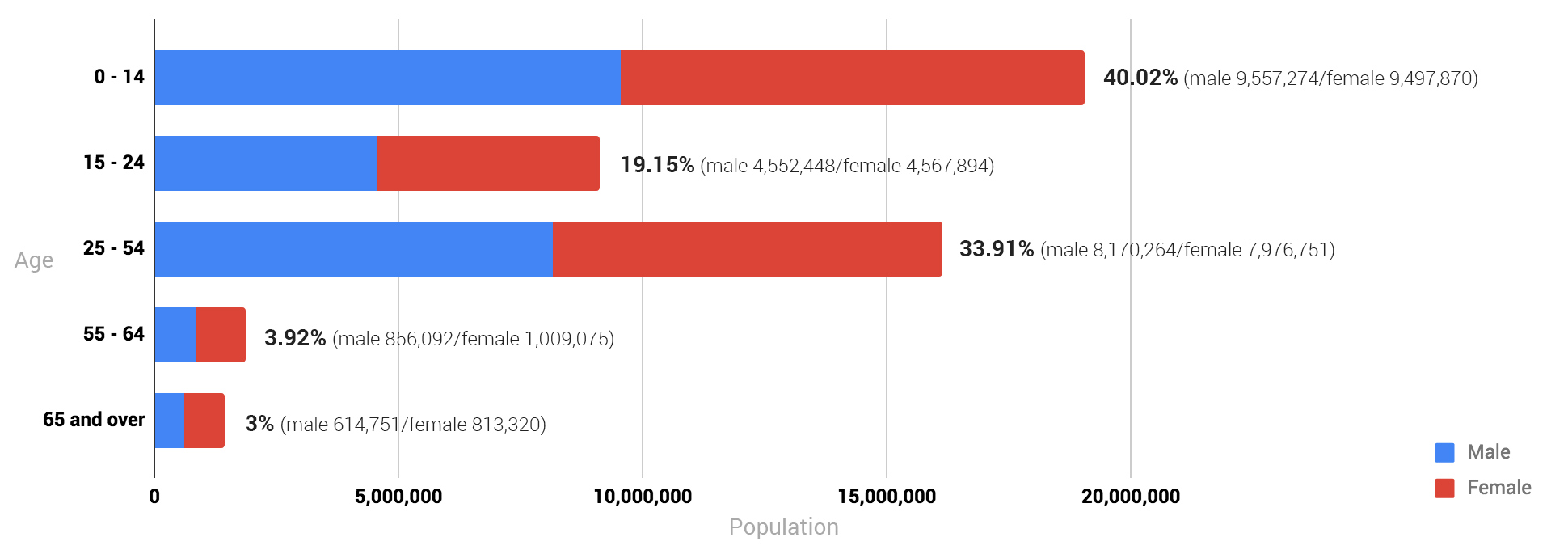

Population growth in the form of natural increase and mass migration is one of the primary forces of historical change. However, demographic structure is acknowledged to be the more important indicator for developmental policy. The latest population numbers for Kenya provide the quantitative parameters of the country’s shifting generational balance.

Kenya Population Structure, 2017

Source: CIA World Factbook

The backlash against the elders highlighted in many of the Elephant’s Millennial Edition is tempered by their relative scarcity. The elderly – people over the age of 65 – now comprise only three per cent of Kenya’s 48 million population. The 25-54 age group’s current share of the population is now one-third larger than it was in 1975.

One notices the difference conveyed by these statistics as soon as you step off the plane almost anywhere in the northern hemisphere. America’s retiring Baby Boomers, for example, are 16 per cent of the U.S. population. In South Korea, so often cited to underscore the two countries’ diverging economic pathways over the past several decades, the figure is 13.5 per cent. The world’s estimated average is edging towards 10 per cent and growing; the trend will translate into a global reduction in household savings and returns on financial assets. This will reduce the growth of household wealth from the historical mean of 4.5 per cent to 1.3 per cent over the next two decades, according to research on global demographic trends.

These numbers qualify the demographic dividend David Ndii referred to in his contribution to the discourse. Formally defined, the demographic dividend is the accelerated economic growth assisted by a decline in a country’s mortality and fertility and the shift in the age structure of the population. This dividend can be activated when pro-human capital policies combined with a large working-age population create virtuous cycles of wealth creation.

The dividend accounted for an estimated two-fifths of the Asian economic miracle. Now it may be Africa’s turn. Population numbers are moving in this direction, but there are basic prerequisites that must be in place for it to happen. Flexible labour markets, quality education systems and health services, and outward-looking economic policies are conventional elements of the formula.

Kenya’s formal policy framework meets most of the criteria. Despite the slower than expected fertility rate decline, Kenya’s dependency ratio is hovering between 76 per cent and 80 per cent. This means one working individual currently supports up to four dependents, but the ratio will decline, bringing Kenya in the rank of countries expected to reap the dividend. But there is no guarantee that this will happen, as the dividend is time-bound. The equation has real and potential implications for millennials, especially considering that important economic indicators, such as investments and savings, are trending in the opposite direction.

The demographic surge raises the stakes for getting policy right. In the case of Latin America, weak governments and closed economies saw large areas forfeit their dividend during the years between 1965 and 1985. Comparative analysis indicates the interactive effect of policy and demography accounts for 50 per cent of the growth gap between Latin America and East Asia. The corresponding observations about demographic deficits, or the failure to maintain living standards due to population decline or other systemic inefficiencies, underscore the imperative of getting the long-term policy equation right.

The demographic surge raises the stakes for getting policy right. In the case of Latin America, weak governments and closed economies saw large areas forfeit their dividend during the years between 1965 and 1985.

Japan and Europe are now going through the decline phase of their demographic transition. Socio-economic change diminishing the role of extended families and other social mechanisms exacerbates the problem, requiring that the state enact effective social policies to bridge the gap. Although post-war Japan maximised its dividend, it is still having problems coping with a population that is shrinking and aging at the same time. Despite its sustained economic growth, almost half of South Korea’s citizens aged over 65 now live in relative poverty, defined in this case as earning 50 per cent or less of median household income. High levels of isolation and depression have led to a dramatic rise in suicide among the elderly, from 34 per 100,000 people in 2000 to 72 per 100,000 people in 2010.

The United States, in contrast, has traditionally relied on immigration to maintain its working-age population. This has countered the aging variable while sustaining a major source of socio-economic revitalisation in the form of new blood and cultural diversity. The noise from President Donald Trump and his base conflicts with the fact that the 75 per cent of Americans support immigration, and they report that the diversity of immigrants makes the country a better place. The country has systematically capitalised on this multicultural dividend to rejuvenate the population and refresh its economy throughout its history. Present controversies over uncontrolled immigration and refugee influxes camouflage the fact that Europe has lately been following a similar – though undeclared – policy pathway.

Demographic transitions typically involve a large jump in population followed by a steady decline as investment in fewer children replaces the risk-spreading and agricultural labour function of large families. In Kenya, where the fertility rate remained in the mid-3 per cent range until the last decade, perhaps the prolonged transition to “adulating” lamented in some of the millennials’ accounts may hasten the fertility rate to drop to the replacement level of 2.1 children per woman from the 2.7 of the past decade.

The employment numbers indicate that the process of reaping the dividend here is less linear and subject to the distinctive features of Kenya’s geography and domestic politically economy. The median age in Kenya is now 19, and Kenya’s 39 per cent overall unemployment rate translates into 22 per cent for youth. The numbers for neighbouring countries are much lower: 4.1 per cent for Uganda; 5.2 per cent for Tanzania; and 3.1 per cent for Rwanda. Even Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country, has a significantly-below-Kenya youth unemployment rate of 13 per cent.

Even though we should not accept all these economic numbers at face value (the less visible parallel economy that doesn’t show up in official statistics is an important source of informal sector livelihoods in Kenya), we may be facing the politically explosive demographic overload scenario that was detailed in the State Department study twenty years ago.

The median age in Kenya is now 19, and Kenya’s 39 per cent overall unemployment rate translates into 22 per cent for youth. The numbers for neighbouring countries are much lower: 4.1 per cent for Uganda; 5.2 per cent for Tanzania; and 3.1 per cent for Rwanda. Even Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country, has a significantly-below-Kenya youth unemployment rate of 13 per cent.

The demographic dividend has a finite window; it does not occur automatically. Both the policies and their timing are critical, which is why Kenya’s millennials are facing a two-pronged dilemma: unemployment is high yet some 47 per cent of the Kenyans sampled in a 2014 Pew Research Survey reported that aging is a major problem. The figures for populous Nigeria, crowded Egypt, and middle-income South Africa came in at 28 per cent, 23 per cent, and 39 per cent in comparison, respectively.

These factors raise the stakes for Kenya getting things right now. But there is more at the crux of the debate than economic policy and warm bodies. Technological innovation works with population increase to drive human adaptation, and developments are moving rapidly on this front.

The fast-moving advance of the fourth technological revolution suggests that Kenya and its neighbours in Rwanda and Ethiopia have the potential to jump the queue if they position themselves properly for the longer run. Negative implications of artificial intelligence for the future of work should not distract us from the benefits on the horizon. The technology sector and building the industrial Internet may serve the same role that manufacturing did in Asia, although the potential for the same demo-techno double dividend cannot be taken for granted.

Assessments of African economic trends now argue that Africa is not likely to transit through the phase of manufacturing and carbon-driven energy generation that powered the post-World War II rise of East Asia and other world regions. Fourth generation technologies, in contrast, can generate an equivalent rise in prosperity and economic growth. This will come about through their contribution to everyday economic domains like health care, resource management and precision agriculture. Digital platforms are already creating a new small-scale ecosystem for commodity marketing, financial inclusion, and women’s empowerment according to one Kenyan expert.

The potential for tech-driven growth will require more than the tech hubs being established in Africa’s tech-friendly countries. It requires the kind of unorthodox and often irreverent problem-solving mindset that the country’s education system is adept at quashing.

The dynamic relationships linking scientific research, applied technology, and venture capital are critical to contemporary processes of innovation. This requires an enabling cultural environment, as demonstrated by the rise of American tech hotspots in the San Francisco Bay area, North Carolina’s research triangle, and the northeastern corridor. These hotspots were not planned; rather, the presence of top research universities and a culture of critical thinking and entrepreneurial risk-taking enabled their rise to prominence over the past three decades.

Kenya’s economy was building towards a transformational tipping point before events saw the country drift into a nebulous purgatory of ethnic polarities and failed constitutionalism. Now deficit financing of infrastructural projects and massive corruption are continuing to remove from circulation critical resources that could be energising the younger generations’ pent-up human capital.

The future availability of such investment capital cannot be taken for granted. It may decline apace with the industrial world’s demographic deficit over coming decades. Then again, demographic trends and the historian John Illife’s treatise on The Emergence of African Capitalism suggest that the continent just may step into the gap. (This was in 1981.) The importance of this synergetic union of capital and labour happening now extend beyond the African continent due to the significance of Africa’s expanding share of the world’s economically active population for the world economy.

Kenya’s economy was building towards a transformational tipping point before events saw the country drift into a nebulous purgatory of ethnic polarities and failed constitutionalism. Now deficit financing of infrastructural projects and massive corruption are continuing to remove from circulation critical resources that could be energising the younger generations’ pent-up human capital.

Beyond demography and economic policy

The first thing that strikes me when I get off the plane back in Kenya is the high level of activity almost everywhere one looks. The country is bursting with energy, but some of it is misdirected and much of it is generating low per capita returns.

The former World Bank head for Kenya, Apurva Sanghi, attributes the mismatch between job requirements and the shortfall of skilled labour due to the poor quality of education. This mismatch clashes with the millennials’ claims about their high level of education. The dramatic growth in universities in Kenya saw quantity replacing quality and the acquisition of paper qualifications displacing the search for knowledge. The commercialisation of higher education has in effect been another drain on the economy that has deprived a large segment of the millennial generation of the skills commensurate with their degrees and diplomas.

The more one studies the data, the more muddled the already uncertain big picture becomes. Even so, the long-term fundamentals, including the country’s 5 per cent per annum growth rates, are at best just okay.

As the latest World Bank overview for Kenya states, Kenya has the potential to be one of Africa’s success stories. All the country has to do is address “the challenges of poverty, inequality, governance, the skills gap between market requirements and the education curriculum, climate change, low investment and low firm productivity in order to achieve rapid, sustained growth rates that will transform lives of ordinary citizens.”

This is a very tall order and until this happens the country will continue to face the risk of stagnation and a creeping demographic deficit. The clock is ticking. In any event, the country needs more than the population-based dividend to drive its transformation. Assuming that demographic growth and the right policies do account for up to 40 cent of the Asian economic miracle, where did the other 60 per cent come from?

Japan and the Asian Tiger nations achieved their reputation through rapid growth compacted within the space of several decades. The demographic dividend is the central component in the developmental mantra explaining East Asia’s remarkable transition. The dividend was activated by policies that combined agricultural commercialisation, liberalisation and the relaxing of state controls, fostering a combination of domestic industry and export-led growth with favourable international economic conditions.

South Korea, the most popular exemplar for other developing countries, implemented deliberate population policies and pragmatic economic guidelines that helped create an age structure facilitating its rapid transition from an agrarian to an industrial society during the short interval between 1960 and 1990. The mutually reinforcing economic and population policies resulted in a basic shift at the household level, with changes in women’s roles and the rise of a middle class in place of the formerly dominant land-owning aristocracy.

The Asian exemplars counteracted the influence of Malthusian assumptions on post-independence developmental thinking, and now the Chinese model figures prominently in the calculations of many African political decision-makers. The Lamu Port, South Sudan, Ethiopia Transport Corridor (LAPSSET) project is emblematic of the focus on large infrastructure projects, natural resource exports, and extractive industries. The proposed Konza Technology City is another worthy but flawed project representative of the central command approach. The coders, investors, nerds, and hackers are not thrilled about moving to a corporate complex in the hinterland in the tradition of sparsely inhabited cityscapes like Brasilia, Morogoro, and China’s Xiongan megacity.

Asia’s big blueprint approaches were consistent with the central planning tradition and Confucian ideologies of social harmony that justified past South Korean and present Chinese and North Korean dictatorships. But there was nothing particularly harmonious about the Asian developmental processes that grew out of the region’s intense internal and territorial struggles, all of which reflected the zero-sum stakes of the era’s ideological conflicts. The triumph of capitalism in that region was anointed with blood, napalm, and genocidal pogroms. The success of the Asian Tigers was the culmination of a long fight that began with imperialism and led to new policies midwifed by fierce competition within old societies sharing similar environmental settings and socio-economic constraints.

Africa’s distinctive features, however, contrast with the conditions underpinning the Asian developmental orthodoxy. In the case of Kenya, competition between communities and opposition to the state prevail whereas in Asia competition and conflict were over ideology and economic models. Growing local opposition to centrally-planned projects in places like Turkana, Isiolo, and Lamu is indicative of the kind of political and social obstacles now complicating the next phase of the proverbial way forward.

Milk, as the pastoralists’ blockade of the road to Lodwar indicates, is still thicker than oil in the Horn of Africa.

It is interesting that the Marxist planners of the superpower era in Eastern Europe saw artificial intelligence as the natural ally of socialist development. AI may still prove to be an antidote to the inequities promoted by neoliberal capitalism. Where Western advisors stressed population control, their socialist counterparts in Africa saw population growth as integral to the continent reclaiming its position on the world stage. The prospects of this happening over the next several decades reminds us that Marx was one of the few analysts to critique the natural laws of Malthus when he postulated that each society at each point in history has its own laws that determine the consequences of population growth.

In traditional African systems, these laws often reflected the dynamics of generational succession. The cultural emphasis on the wisdom of the elders supported their embedded cross-generational influence on decision-making. I witnessed negative examples of this tradition in my children’s schools, where on more than one occasion, I lost arguments with fellow parents over issues like setting up computer labs and Internet connections. Kenya’s fossilised education system is one of the culprits responsible for the under-35ers’ angst, and this is corroborated by another recent essay on the multidimensional crisis plaguing higher education, published in The Elephant.

Has the generational model of African development hit a wall? The unproductive transfer of generational assets that formerly sustained capital formation is undermining productivity in the highland areas that fueled Kenya’s post-independence prosperity. When parents die they bequeath their wealth to their children, and this powered economic growth and diversification in the past. This vector is now turning family farms into dead capital as the owners age and their children working outside the sector block the sale of family land. The widespread leasing of small acreages and the break-up of large farms into parcels for rent is one symptom of a malaise that impacts beyond the agricultural sector.

The economic planners that once fostered Kenya’s economic growth have morphed into bureaucrats trapped in the development administration contradiction Bernard Schaffer identified in 1969. Schaffer argued that the first imperative of state administrators is to conserve and protect their bureaucracies while “development” is essentially an entrepreneurial activity. Kenya’s cartels and tenderpreneurs offer proof of the term’s oxymoronic logic.

Everywhere the millennials look they see dead ends, or so it seems from the urban point of view. Ndii’s “Hustler Nation” essay argues that multiple productivity enhancing interventions in rural areas will generate far more to youth employment and productivity than the mega project revenue vampires they have conjured up. The resources allocated to building a tech city, for example, would be better invested in interdisciplinary IT programmes hosted by universities across the country, and other nodes dedicated to addressing economic activities ripe for innovation.

Everywhere the millennials look they see dead ends, or so it seems from the urban point of view. Ndii’s “Hustler Nation” essay argues that multiple productivity enhancing interventions in rural areas will generate far more to youth employment and productivity than the mega project revenue vampires they have conjured up.

These are the kind of issues that the millennial generation intellectuals and activists would do well to explore and debate. Their future, if not present welfare, will likely depend on developing creative developmental formulae consistent with the region’s historical trajectory and distinctive socio-cultural variation. A shift in this direction is beginning to gather speed on the county level, where the stakeholders are much better situated to generate the adaptive policies needed to maximise the demographic dividend.

In any event, we now know that progress is more a function of trial and error than the strategic planning processes and interventions managed by actors who remain insulated from their failures and unintended consequences. Devolution generates local initiatives, like the Makueni County public health revolution, which can be replicated and tweaked to fit the conditions in other settings.

Considering the obsession with branding of almost every Kenyan enterprise, with its vision and mission statements, more expansive thinking on these issues is one area where The Elephant’s Millennial Edition articles came up short. But they are not, as David Ndii contended, “on their own”. In addition to their rural age-mates, there is a growing transnational movement out there that is beginning to coalesce into a mass generational movement.

I hope it happens. Africa does need to regain its rightful place in the world, and someone needs to rescue the species from the Trumpian values of late capitalism.