Fifty-five years ago, on July 26, 1963, the national flag of the soon to be newly independent state of Kenya was unveiled. The standard was typical of the country that had created it – cobbled together by an elite but imbued with pretensions at unity and forging common cause with common folk.

In those heady days, as Kenya geared up to party, one could be forgiven for ignoring the tensions bubbling underneath. The country was in transition and the previous two years had been marked by political crisis, brinkmanship and even threats of war and secession. As described in 1964 by Guardian journalist Clyde Sanger and former official in the Kenyan colonial administration, John Nottingham, “During this period Kenya first experienced six weeks when neither [of the two major political parties, the Kenya African National Union or the Kenya African Democratic Union] would form a government and [Governor Patrick Renison] told visitors he was prepared to rule by decree; 10 months in which K.A.D.U., with backing from Michael Blundell’s New Kenya Party and Arvind Jamidar’s Kenya Indian Congress, carried on a minority government sustained by more than a dozen nominated members; and a year in which K.A.N.U. and K.A.D.U. uneasily joined in a coalition which was as full of frustrations as it was of intrigues. The politics of nation-building could not even begin until K.A.N.U. had fought and won a straight democratic election”.

Today, the messy story of Kenya’s struggle for independence has largely been swept under the symbolism of the flag, yet the contradictions and disputes that gave rise to it continue to haunt the nation as they were never fully resolved. The tale of the flag itself is a manifestation of these issues.

Symbolism

Historically, flags were linked to conflict. “The primordial rag dipped in the blood of a conquered enemy and lifted high on a stick – that wordless shout of victory and dominion – is a motif repeated millions of times in human existence,” wrote Whitney Smith in his book Flags Through the Ages and Across the World. Modern flags evolved out of the battle standards carried into war by ancient armies and “were almost certainly the invention of the ancient peoples of the Indian subcontinent or what is now China” according to the Encyclopedia Britannica.

Today, the messy story of Kenya’s struggle for independence has largely been swept under the symbolism of the flag, yet the contradictions and disputes that gave rise to it continue to haunt the nation as they were never fully resolved. The tale of the flag itself is a manifestation of these issues.

In battle, flags were both symbolic and practical. They provided mobile rallying points for soldiers engaged in combat, could be used to signify victory or even, in plain white form, a truce or surrender. In the days before radio communications, they were also ways of communicating across vast distances, especially by sailors. In the modern age, they are still carry powerful symbolic significance. “Show me the race or the nation without a flag, and I will show you a race of people without any pride,” Marcus Garvey was reported to have declared in 1921.

On the African continent, almost all the current national flags were created in the years following the Second World War and in the run-up to the demise of colonialism. Many still bear hallmarks of that colonial past. According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, the ensigns of countries that had a common colonial past “bear strong family resemblances to one another”. It distinguishes two major categories: those former French colonies which “tend to have vertical tricolours and are generally green-yellow-red” and those of the Anglophone which “have horizontal tricolours and often include green, blue, black, and white.”

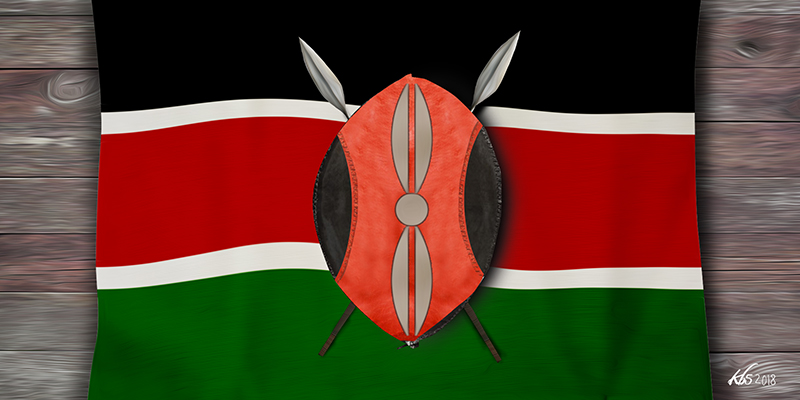

The colours

Kenya’s standard also carries this history. It can be traced directly to that of the Kenya African Union, which was founded in 1942 under the name Kenya African Study Union, with Harry Thuku as its president. The flag of the KAU (the word “Study” was dropped in 1946) adopted the Pan-African colours pioneered by Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League 25 years before – red, black and green, which respectively represented the blood that unites all people of Black African ancestry and which was shed for liberation; the race of black people as a nation; and the natural wealth of Africa. (It must be noted, though, that some have suggested that when Garvey proposed the colours, he meant the latter two to reflect sympathy for the “Reds of the world” as well as the Irish struggle for freedom.)

However, when originally introduced on September 3, 1951, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica, KAU’s flag was only black and red with a central shield and arrow. The following year, the background was altered to three equal horizontal stripes of black, red and green with a white central emblem consisting of a shield and crossed spear and arrow, together with the initials “KAU”. At the time the black stood for the indigenous population, red for the common blood of all humanity, green symbolised the nation’s fertile land while the shield and weapons were a reminder that organised struggle was the basis for future self-government.

Jomo Kenyatta took over the presidency of KAU from James Gichuru in 1947. Five years later, as reported by Karari wa Njama, a Mau Mau veteran and alumnus of Alliance High School, in the book Mau Mau from Within, Kenyatta’s explanation of the significance of the KAU flag had changed. “What he said must mean that our fertile lands (green) could only be regained by the blood (red) of the African (black). That was it! The black was separated from the green by the red: The African could only get to his land through blood.”

Kenyatta was speaking in Nyeri as the Mau Mau uprising was gathering steam. Though billed as a KAU meeting, Karari says that “most of the organisers of the meeting were Mau Mau leaders and most of the crowd Mau Mau members.

“What he said must mean that our fertile lands (green) could only be regained by the blood (red) of the African (black). That was it! The black was separated from the green by the red: The African could only get to his land through blood.”

Yet Kenyatta himself had little to do with the Mau Mau. On the contrary, he consistently denied any involvement with them and is, in fact, reported – on the same day – as having distinguished the KAU from the uprising and having disavowed the use of violence. “He who calls us the Mau Mau is not truthful. We do not know this thing Mau Mau…K.A.U. is not a fighting union that uses fists and weapons. If any of you here think that force is good, I do not agree with you: remember the old saying that he who is hit with a rungu returns, but he who is hit with justice never comes back. I do not want people to accuse us falsely – that we steal and that we are Mau Mau.”

However, Karari’s recollection is important given that the red in the Kenyan flag would later be claimed to reflect “the blood that was shed in the fight for independence”.

By 1956, the Mau Mau revolt had been brutally quashed and gradually the restrictions on political organisation were eased. In 1960, the eight-year State of Emergency was lifted and the ban on colony-wide African political parties relaxed. KANU was founded on May 14 of that year and, as Charles Hornsby writes in his book Kenya: A History Since Independence, “its name, black, red and green flag and symbols were chosen as a direct successor to those of KAU”. At some point, the cockerel and battle axe were introduced as symbols of the party. A month later, on June 25, KADU was formed. John Kamau, an Associate Editor with the Daily Nation has written that the “Kanu and Kadu flags were similar in design. Both had three horizontal bands and two similar colours, black and green. The difference was only in the third colour, red for Kanu and white for Kadu.”

KANU was dominated by the large agricultural communities – the Kikuyu and Luo – while KADU represented smaller, mostly pastoral ones, which feared domination. KANU won the 1961 election but refused to form a government before Kenyatta, who had been detained in 1952, was released. KADU, after extracting some concessions from the British, which included building Kenyatta a house in Gatundu and moving him there, formed a minority government with its head, Ronald Ngala, as Leader of Government Business and later as Chief Minister.

Majimboism

It was only in September, after it had been in power for five months, that KADU begun to foster an issue that would come to define the conflict between the two parties. KADU espoused Majimbo, or regionalism, in opposition to KANU’s preference for a highly centralised post-independence state. KADU was egged on by the white colonial establishment to adopt this stand.

As explained by Sanger and Nottingham:

“Majimbo’s origins should be traced further back, to Federal Independence Party formed in 1954 by white farmers, who saw that political control would one day pass into African hands and wanted to seal off the ‘White Highlands’ from an African central government and save the great wealth of the Highlands for those considered had been solely responsible for developing it.

“Indeed, regionalism really goes much further back than this. Elspeth Huxley recalls that the F.I.P. was only proposing to ‘develop the “white island” idea … to carve out a small territory, about the size of Wales, comprising present areas of the Highlands. In this area they would exercise self-government; so would the Africans in other areas; and Kenya would become a federation of three or four smallish states, in only one of which would the colonists have political control. Here they would entrench themselves.’”

It is interesting that devolution, which is rooted in the Majimbo debates, has become a pillar of the 2010 constitution. Many Kenyans do not realise just how much current political debates are a reflection of much older, and not always innocent, proposals.

KANU, in opposition, was vociferously opposed to Majimbo, which it saw as entrenching tribalism. And by the second Lancaster House Constitutional Conference, which lasted from February to April 1962, both sides seemed, at least rhetorically, firmly entrenched in their positions.

It is interesting that devolution, which is rooted in the Majimbo debates, has become a pillar of the 2010 constitution. Many Kenyans do not realise just how much current political debates are a reflection of much older, and not always innocent, proposals.

But it was mostly for show. As Prof. Robert Manners wrote at the time, “The contesting parties are less divided by issues, programs, and even concepts of political structure than they are by competing personal ambitions.” He added that he had spoken to several within the KADU camp, including two front benchers, who told him that they were not really afraid of KANU domination but rather, were cynically hyping up fears for personal benefit. “In short, it is fairly certain that KADU’s leadership does not share the ‘tribal’ fears they have helped to arouse in their followers. They have employed some ancient anxieties and provoked a number of new ones with the apparently calculated intent of prolonging in some measure and for some time the freakish position of power with which they were endowed when KANU refused, in April 1961, to form a government.” Sound familiar?

Regardless, the outcome of the conference was a coalition government led by both Ngala, the Minister of State for Constitutional Affairs with special responsibility for administration, and Kenyatta, who had since been released and was now the Minister of State for Constitutional Affairs with special responsibility for economic planning and development. Each declared victory.

This “nusu mkate” government was a fractious affair from which Kenyatta’s Number Two in KANU had been excluded at the insistence of the Colonial Office. In his book, Not Yet Uhuru, Oginga Odinga speculated that “Governor Renison persuaded the Colonial office that my visits to Socialist countries made me unfit to take Cabinet office”. He was also aware of “behind-the-scenes discussions in London in which some Kanu men hinted that I would be unacceptable not only to Kadu but even to some groups in Kanu”.

Still, the coalition held till the elections in 1963, which KANU again won handily and this time they got to form the government, with Kenyatta as Prime Minister. In June, Kenya attained self-government and arrangements for independence began in earnest. Among the issues that would need to be settled was the question of a political union with neighbouring Uganda and Tanzania. As late as July, the idea of an East African Federation was still being taken seriously.

East African Federation debate

A month before, on July 5, Kenyatta and his Ugandan and Tanganyikan counterparts, Milton Obote and Julius Nyerere, had issued the Declaration of Federation, in which they committed to establishing a political federation by the end of the year. This was another idea with a long history, pioneered by the white colonial settler establishment who, as far back as the 1920s, were ready to establish a federal capital in Nairobi in order to reduce the influence of London in the region.

The region was already tied together by a network of more than 40 different East African institutions covering areas such as research, social services, education/training and defence. As Nyerere had observed in March, “A federation of at least Kenya, Uganda and Tanganyika should be comparatively easy to achieve. We already have a common market, and run many services through the Common Services Organisation…This is the nucleus from which a federation is the natural growth.”

When the issue came up for debate in the UK’s House of Lords on July 15, Francis Twining warned of the difficulties of federation since it involved the loss of sovereignty which “these new countries value … above all else. They jealously prize their status symbols, such as national flags and national anthems”.

And, as Nyerere himself would admit 34 years later, flags and other national symbols, rather than tools to rally unity, had become tools of personal aggrandisement and actually stood in the way of such unity. “Once you multiply national anthems, national flags and national passports, seats at the United Nations, and individuals entitled to 21 guns salute, not to speak of a host of ministers, prime ministers, and envoys, you have a whole army of powerful people with vested interests in keeping Africa balkanised.” Across the continent, attempts at political federation met quick deaths.

And, as Nyerere himself would admit 34 years later, flags and other national symbols, rather than tools to rally unity, had become tools of personal aggrandisement and actually stood in the way of such unity.

As Kenya moved towards independence, some within Kenyatta’s circle wanted to use the KANU flag as the national flag. This was not without precedent. As Tom Mboya, the brilliant young Justice and Constitutional minister, noted, “It is not without significance that our neighbours, Tanganyika and Uganda, both saw it fit to use the ruling party flag simply as a basis for the national flag.”

However, Mboya cautioned against simply adopting the KANU flag, warning that it would further polarise the country. He managed to convince Kenyatta, who formed a small committee chaired by Dawson Mwanyumba, the Minister for Works, Communication and Power, to come up with the national colours. Doing so was not difficult because he was not really looking for national colours but rather a political compromise everyone could live with. So he did the obvious thing and combined the colours of the KANU and KADU flag by introducing the white fimbriation. The flag retained and updated the elements of the KAU flag, such as the shield and spears. The KANU cockerel and axe were omitted from the flag but made it onto the coat of arms.

When the flag was shown to the cabinet, the meaning of the red colour matched what Karari had understood Kenyatta to say over a decade before. Rather than simply including KADU, the white fimbriation was said to symbolise a multiracial society but the cabinet changed it to “peace”, perhaps a sign that while racial minorities would be tolerated in the new Kenya, their integration was not necessarily on the agenda.

Talks of secession

But there were other issues related to minorities to be settled. In the northeast, the Somali population was in open revolt. A 1962 survey had found that 85 percent of Somalis preferred to join Somalia. However, in March 1963, Duncan Sandys, the Colonial Secretary, under pressure from Kenyan ministers, supported a Kenyan future for them. This sparked mass protests, an election boycott, calls for armed secession and attacks on government facilities. By November, the so-called Shifta war was raging, with audacious attacks by rebels armed and trained by Somalia.

In Nairobi, Mboya pushed an amendment to the National Flag, Emblems and Names Act to outlaw the display of flags purporting to represent Kenya or a part thereof. This was meant to stop the Somalis flying the Somalia flag in the Northern Frontier District. But it also had other targets.

At the third and final Lancaster House Constitutional Conference, held between late September and mid-October 1963, tensions were so high that KADU leaders Ngala and Daniel arap Moi, who had been elected President of the Rift Valley Region, threatened to secede from Kenya, with Moi releasing a partition map and threatening a unilateral declaration of independence. (Again, sound familiar?) There were even suspicions of an alliance with the Somalis in the NFD, which were fueled by a cable from Jean Seroney, at the London talks, to Moi: “Dishonourable betrayal of majimbo agreement by Britishers. Alert Kalenjin and region and Kadu to expect and prepare for worst. Partition and operation Somalia only hope.”

Mboya’s motion was thus not just aimed at the Somalis; the threats of secession by KADU regions had to be put down and one way was to deny them the right to fly flags purporting to represent an autonomous, or even independent, part of Kenya. Local councils, though, like the Nairobi City Council, were allowed to have their own flags.

There would be more drama surrounding the flag on independence day. The symbolism of lowering the Union Jack at midnight right before the Kenyan flag went up was profoundly discomfitting to the British. They determined that their flag would not be raised for the event after it had been lowered, as was customary, at 6pm. Kenyatta, who by now was their reliable lackey, was happy to go with it but when he presented the plan to the Cabinet, it was shot down, largely thanks to Mboya. So another plan was hatched with Arthur Horner, the former Permanent Secretary in the Ministry of Works and then the head of the Independence Celebrations Directorate (the body charged with organising the event), who secretly ordered to put out the lights as the British standard came down and switch them back on as the Kenyan flag was raised. It was a ploy the Brits had pulled before, in both Uganda and Tanganyika.

On 30th July, just a few days after the national flag had been introduced, Kenyatta had given a ministerial statement on the independence day celebrations in which he bemoaned the people’s penchant to fly party flags wherever and whenever they desired, declaring it illegal. The national flag, he declared, would only be flown by “Cabinet Ministers and other authorised persons” and its reproduction, along with that of Kenyatta’s own portrait, would be strictly controlled. In this way, under the guise of honouring it, the flag was shielded from the masses and reserved for the glorification of the ruling elite. The flag, and the state it stood for, became the property of a few, not of all Kenyans.

After independence, this “protection” of the flag from the people, who were deemed too unclean to handle it, continued with frequent debates in Parliament about who could and who couldn’t fly it. Under Jomo Kenyatta’s successors, the law and the policy has remained largely unchallenged.

Reclaiming the flag

But the last two decades have seen the beginnings of a popular movement to claim the Kenyan flag. It has become ever more present in Kenyans’ lives – from activists like Njonjo Mue, who in 2004 scaled the walls of Parliament and ripped the flag off a cabinet minister’s car as a way of demonstrating the government’s loss of moral authority to govern, and who more recently has been charged with flying the flag on his own car, to the many Kenyans brandishing it during public rallies and sporting events (it even famously made an appearance at the World Cup) it seems that, as Kenyatta feared 55 years ago, “every Tom, Dick and Harry” is flying it. He must be turning in his mausoleum. Good.

After independence, this “protection” of the flag from the people, who were deemed too unclean to handle it, continued with frequent debates in Parliament about who could and who couldn’t fly it. Under Jomo Kenyatta’s successors, the law and the policy has remained largely unchallenged.

However, besides reclaiming the use of the flag, Kenyans need to also consider what it means today. If it is not to be a tool of personal aggrandisement or unthinking and enforced veneration of the state, then what should it be used for? Who or what does it represent?

In the years since independence, it has been a symbol, not of Kenyans and their struggles against oppression, but of Kenya and the power it continues to be wielded against them. The rituals associated with the flag and other symbols such as the national anthem, both reinforce and, paradoxically, disguise this. It is clear in the common statement that “Kenya is greater than any one of us” which at once distinguishes Kenya from Kenyans while also proclaiming the myth that the state is something more than a largely self-serving political arrangement between elites competing for power and prestige. Kenya, we are rather told, is a divinely-ordained an eternally established ordering of Kenyans to which we all owe allegiance and subservience. It recalls a time in my childhood when I was informed that suicide was illegal because it deprived the state of taxes, as if Kenyans were made for Kenya and not the other way around.

In the week where we mark the anniversary of Kenyatta’s “Tom, Dick and Harry” statement to the House of Representatives, perhaps we could all take some time to remember all the history – good and bad – that the flag represents, as well as reflect on what else it could stand for.

We can choose, and many are choosing, to reinterpret its design and colours to suit, not the ambitions and egos of politicians, but the realities and aspirations of ordinary Kenyans. As it did for Karari wa Njama all those years ago, it should today serve as a reminder of the need to continue the struggle to free ourselves from the existing colonially-inspired order – that despite 55 years of independence, the black is still separated from the green.