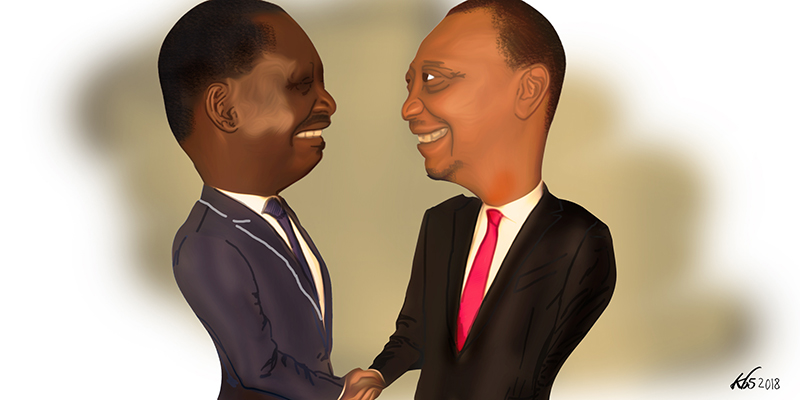

On March 9, 2018, at around 1.00 pm, Kenya’s tepid political weather experienced a sudden and powerful jolt when President Uhuru Kenyatta, the country’s elected president, and his political opponent, Raila Odinga, the so-called “People’s President”, were shown walking together and shaking hands on the stairs of Harambee House. The fiercest protagonists of the recent bare-knuckle political contest had met and were photographed at the seat of government offices, smiling and walking side by side.

On seeing Raila’s entourage enter the Office of the President, Njee Muturi, the Deputy Chief of Staff, is reported to have told Junet Mohammed (one of the politicians who had accompanied Raila): “When I see you people here and being welcomed like this, I am not even sure my job is safe anymore.” The others who accompanied Raila on this unexpected visit were Raila’s daughter, Winnie Odinga, Paul Mwangi, his legal advisor, and Andrew Mondoh, a former Permanent Secretary in the Ministry of Special Programmes, a ministry created during the coalition government of Mwai Kibaki and Raila Odinga.

“Our future cannot be dictated by the forthcoming election,” stated President Uhuru Kenyatta as Raila stood beside him. The next general election is slated for 2022 – barring a constitutional crisis or political tsunami. “Prosperity and stability…and the well-being of our people” is what should dictate that future, said the president. Raila, echoing Uhuru’s statement, said: “My brother and I have therefore come together today to say this descent stops here,” It was instructive that Deputy President William Ruto was not a witness to the handshake that brought to an end a bitter rivalry that began five years ago during the 2013 election.

Many Kenyans across the political divide welcomed “the handshake” even though at least half the country was still nursing wounds precipitated by the 2017 elections that had deeply polarised the country: the “Jubilants” vs “ the Nasarites”, the Kikuyus/Kalenjins vs Luos, the centrists vs secessionists, the pro-establishment vs the anti-establishment. Although the National Super Alliance (NASA) opposition coalition is made up of a conglomerate of ethnic communities, the Jubilee Party and the government had politically profiled NASA as a Luo affair in the lead-up to both the August 8 and October 26 elections last year. This was evident in the violence that was visited upon Luo youth by the state, especially in the lakeside town of Kisumu.

Many Kenyans across the political divide welcomed “the handshake” even though at least half the country was still nursing wounds precipitated by the 2017 elections that had deeply polarised the country.

In the years to come, body language experts will study the video clips of the Uhuru/ Raila handshake and unravel what was going through the protagonists’ minds and what their bodies were communicating to each other and to the outside world.

Raila’s first stop after the handshake was at the Kondele ghetto suburbs in Kisumu, and not, as would have been the norm, at the sprawling Kibera slum in Nairobi, home to his most fanatical and loyal urban support base. Many of the Luo youths who were killed by the state’s paramilitary machinery were from Kondele, a bastion of militant Luo youth.

John Okoth from Kondele called to tell me: “Baba [the moniker given to Raila by his supporters] came over this evening and gave us assurance that families that lost their sons would be compensated. He begged us to listen to him. But I can tell you the youths are still in a militant mood.” Okoth said that not everyone in Kisumu was convinced or happy or even knew how to react to the handshake. “The people are confused and divided about it. Their one big question is: So after the beatings by the state’s violent apparatus, the killings of youth, then the handshake comes. That is so confusing.”

The unanticipated handshake has spawned conspiracy theories; many believe that there was a secret pact between the two whose contents may never be known. “As long as it is only a few Kenyans who were privy to the events that led to the handshake, we will for sure never know what actually transpired between Uhuru and Raila,” said a National Intelligence Service (NIS) officer who knows both leaders well.

Talk within the corridors of power suggests that the relationship between President Uhuru Kenyatta and his deputy, William Ruto, has been frosty recently. An incident that took place at Harambee House on the day of the great handshake could be a pointer to this ostensible mutual distrust. As journalists were waiting for President Uhuru Kenyatta and Raila Odinga outside the building, the Recce Squad that guards the building noticed a lone policeman also hanging around. Some of the Recce paramilitary approached him and asked him: “Na wewe ni nani na unataka nini? Kwa nini unaoneshana bunduki? Toka hapa mara moja, tusikuoane hapa tena” (Who are you and what do you want? Why are you exposing your gun? Get out of here). Apparently, the policeman had his pistol holster strapped on. The policeman walked away quietly.

Another theory is that Kalonzo Musyoka, Musalia Mudavadi and Moses Wetangula – Raila’s co-principals in NASA – had planned to defect to Jubilee on the Saturday before at Sugoi, Ruto’s Eldoret home. The plan was to welcome them with fanfare in Ruto’s local political base, which would send the message to Uhuru, Raila and Ruto’s Kalenjin constituency that Ruto was on top of his game and, in a manner of speaking, had hit the ground running. If this theory is true, dismantling the assiduously crafted opposition coalition would have been a feather in Ruto’s cap. The high-profile defections would have sent a message to Raila that he was now truly on his own and that it was time for him to pack up and retire. To President Uhuru, the message would have been different: “Look, I have started consolidating my base and troops – you will have no choice but to support me in 2022.” To his Kalenjin people, it would have indicated that Ruto was still their best bet for capturing State House. (Indeed, the day after the handshake, Ruto made a trip to Uasin Gishu County, probably to reassure his base that all was well.)

In such a scenario, the handshake then would have been a presumptive strike meant to forestall and pre-empt Ruto before he upstaged both President Uhuru and Raila. “Both Uhuru and Raila are agreed on one thing – Ruto would not be good for this country. He is a warlord, a destructionist who doesn’t mean well for the country,” claimed the NIS officer who cannot be named because he is not authorised to speak to a journalist.

“The handshake was a zero-sum game,” he said. “There were clear winners and losers and it does not take much guesswork to know who won and who lost.” Since the handshake, Ruto has been agitated and frantic while his base, the Kalenjins, have been confused, said the NIS man. After calming his base, Ruto quickly headed to the coast region, a stronghold of Raila’s Orange Democratic Movement (ODM) support outside the western region, to incite and offer political promises to those he knew had also been stunned by Raila’s move.

“Both Uhuru and Raila are agreed on one thing – Ruto would not be good for this country. He is a warlord, a destructionist who doesn’t mean well for the country,” claimed the NIS officer.

“Handshake or no handshake, we will not hand over the leadership of this country to the lake Nilotes” said Farouk Kinuthia, a 56-year-old Kikuyu who, although startled by the political rapprochement, hoped it would, at the very least, result in a better business environment. A “tenderpreneur” whose major business is cutting deals with respective national ministries’ bureaucrats, Farouk decried how business had dried up and how the last payments tenderpreneurs like him had received were in April 2017. His interpretation of the handshake was that President Uhuru’s best option in the prevailing circumstances had been to “tame the shrew”. “Raila is a wily politician who must be kept at close quarters, as we observe him and get to know what could be his real intentions. We still intend to vote for William Ruto in 2022.”

Members of the ethnic Kikuyu community, to which Uhuru belongs, know that without a Kikuyu-Kalenjin alliance, the fate of Kikuyus in the Kalenjin-dominated Rift Valley is at stake. Memories of the post-election violence in 2007/2008 that targeted Kikuyus in the Rift Valley still haunt them. The union of Ruto and Uhuru prior to the 2013 elections was motivated not just by the fact that both politicians faced crimes against humanity charges at the International Criminal Court, but that they belonged to communities that have been at war since the 1990s, when President Daniel arap Moi, a Kalenjin, orchestrated ethnic clashes between the Kikuyu and the Kalenjin.

“The Kikuyu people were both shocked and relieved with the handshake. Shocked because the Kikuyu who have over time become politically intolerant of any opposition to their Uhuru Kenyatta and in essence to any force opposed to Kikuyu political dominance, did not anticipate him patching up with Raila, a man Uhuru had fought tooth and nail to retain the presidency – at whatever cost,” said a Central Kenya politician who is well acquainted with both President Uhuru and Raila. “Already torn between throwing their support behind Deputy President William Ruto and finding their own [Kikuyu] successor to President Uhuru, the Kikuyus are at a crossroads politically. With an exiting President Uhuru, who constitutionally cannot run for another term, and with a presumed ‘political debt’ hanging over them that they owe Ruto, the Kikuyus are faced with unprecedented political uncertainty for the first time,” said the politician, who served in President Mwai Kibaki and Prime Minister Raila Odinga’s coalition government between 2008 and 2012.

“Uppermost in their minds, is how they will secure their political insurance once President Uhuru is gone. Split between settling a debt (grudgingly and however painful it is) and charting their own political path – meaning finding a Kikuyu politician to back for the presidency come 2022 – the Kikuyus will welcome any political move that will free them from their anxieties and from skipping a debt that was painfully imposed on them.”

Groups of Kikuyu men and women in Kiambu and Kikuyu towns in Kiambu County were categorical that the handshake did not now mean “that we [Kikuyus] can hand over the reins of power to Raila,” and by extension, to the Luos.” They reminded me of the prophesies of Mugo wa Kibiro, a great Kikuyu seer, some of which are related in Jomo Kenyatta’s anthropological treatise, Facing Mt Kenya. “Ruriri rwa Gikuyu ni rukanyarirwo in karuriri kanini kwa ihida, no nimagacokerio utongoria wa bururi”. In essence, they were saying that Mugo had prophesied that the Kikuyu would be dominated by a small tribe for a while. In their chauvinistic interpretation of the seer’s vision, that “small tribe” referred to the Tugen, former President Moi’s ethnic community. But after that, the Kikuyu would retake the leadership of the country and would not again cede it.

“Does it mean now we are friends with the Luos?” asked a middle-aged Kikuyu businessman. “It is really already too late for anyone to tell us to vote for a Luo. Raila’s name is too besmirched politically among the Kikuyus for them to even contemplate voting for him. The Kikuyu people cannot trust him. This position has been entrenched by Uhuru Kenyatta himself who told us that if Raila assumes the presidency, he will come for us.” The businessman said the handshake had introduced a new variable, but he was still convinced that many Kikuyus would rather vote for Ruto in the absence of not having one of their own candidates.

“With an exiting President Uhuru, who constitutionally cannot run for another term, and with a presumed ‘political debt’ hanging over them that they owe Ruto, the Kikuyus are faced with unprecedented political uncertainty for the first time,” said the politician.

Following the second presidential election of October 26, 2017, among the most economically hard-hit Kenyans were the Kikuyus. Their businesses have hit rock bottom and a majority of their youth are jobless and remain unemployed – a trend that even the political elites are concerned about.

A friend who is a stockbroker and who works for a securities firm surprised me when he told me that his firm had to move from their posh offices in downtown Nairobi because business was really bad. Many Kikuyus have invested in stocks and bonds; some of them have been trading for the last 50 years. Between August 2017 and March 2018, a mzee from Murang’a, who has been trading in shares since 1966, told me times had never been so bad and hard. He claimed to have lost millions of shillings in six months.” On the day of the Uhuru-Raila handshake, the shilling appreciated against the dollar, suggesting that the market was responsive to the political détente.

A Central Kenya politician said that the NASA-instigated boycott of products and companies associated with Uhuru Kenyatta and his Jubilee party had threatened to destabilise many of the businesses operated by Kikuyus around the county, be they long-distance buses that travel to western Kenya and the coast region or retail shops that sell Brookside Dairy products and Safaricom accessories. In just one short month, the blockade had inflicted a serious “profit dent” on Brookside Dairy Ltd (President Uhuru Kenyatta’s family-owned business), especially in western Kenya and some parts of Nairobi.

Even today, as I write, it is not easy to find a retail outlet in western Kenya that openly sells Brookside milk. Peterson Njenga, a tax consultant from Kikuyu town who has been doing some work in western Kenya recently, told me. “Once I asked for Brookside milk from a kiosk and the shopkeeper looked at me like I had asked for salmon fish,” said Njenga. “I was quietly informed the milk is an ‘illegal’ item in that part of the world. It almost sounded like it was contraband. I got the impression that shopkeepers stocked Brookside Dairy products at their own risk.”

But the Kikuyus are not resting easy just yet. A more worrisome question that is being discussed in hushed tones is: What if Raila swallows Jubilee the way he swallowed KANU [President Moi’s party that ruled with an iron fist for 24 years)? This is the talk in Kikuyu-owned restaurants, eating joints, social gatherings and homes. “This man Raila has a way of calming things down. Look the country is a lot less tense and at peace. But what is he up to? Does anybody for sure know? His ulterior motive must be checked and countered,” they say.

After losing to President Moi in 1997, when he contested the presidency for the first time on a National Democratic Party (NDP) ticket, Raila joined the ruling KANU party soon after. However, midway, when Moi was furtively crafting his successor within the party hierarchy, Raila broke ranks with some of his closest loyalists when he settled on a neophyte Uhuru Kenyatta as KANU’s presidential candidate, which necessitated an open revolt.

Raila, who led the rebellion, marshalled support internally and wrecked KANU’s stability, which has seen the party never recover to date. NDP’s symbol was a tractor while KANU’s was a cockerel. “Has the cockerel crowed again ever since it was swallowed by the tractor? Our people, let us be cautious with this handshake, even as we welcome it,” said an elderly Kikuyu. The mzee said that after the cockerel’s crow was choked, KANU was confined to Baringo area and pretty much nowhere else. (Baringo is President Moi’s ancestral home.)

Joseph Kamotho, the then the Secretary-General of KANU, was so riled by this merger and his deposition from his influential seat that he publicly berated his boss President Daniel Moi for the first time, something that he had never done since Moi politically rehabilitated him in 1989, after the “Sir” Charles Njonjo traitor saga in 1983, which led to the sacking of Kamotho. In an interview I had with Kamotho thereafter, the Moi loyalist told me: “Moi will one day come to regret KANU’s dalliance with NDP.” Kamotho was, of course, upset because his powerful party position had been taken away by his political nemesis, but it is also true KANU was never the same again after the entry of Raila and NDP.

A more worrisome question that is being discussed in hushed tones is: What if Raila swallows Jubilee the way he swallowed KANU?

Yet, overnight, in a space of 24 hours, Raila’s narrative among the Kikuyus – of being a political dinosaur – had changed, at least on the Kikuyu-language Kameme and Coro FM stations. (The former is owned by the Kenyatta family and the latter by the national Kenya Broadcasting Corporation (KBC) that had spent the better part of the campaign period lampooning Raila Odinga as a man whose sell-by date had expired.) During the weekend of the handshake, the stations’ respective political commentators and presenters were extolling Raila’s old age as a political virtue and his stature as that of a sage. “Niwamenya Raila niwe uranyitereire Opposition….eta muthuri wina experience ki siasa, niekuhota kutaraniria na Uhuru maundu makonie thirikari.” (You know Raila was the fulcrum of the Opposition…as an elder statesman, experienced in the art of politics, he will work very well with Uhuru in shaping the government.) The stations were effusive with praise for Raila’s political mastery, discovering suddenly that within the NASA fraternity his ODM party was the most popular and influential, with the most MPs even in areas that were not traditionally considered ODM zones.

“Raila is revered almost like a deity,” said a group of Luo elders to me. “Even when he does something we the Luo people do not understand immediately, we cannot publicly berate him. We will complain among ourselves and that is it.” In fact, some Luos from Nairobi told me tongue in cheek: “We had the tyranny of numbers when it came to the youths killed in the aftermath of both elections – we endorse the handshake.”

Not so fast, says Steve Owiti, a businessman from Nairobi. “Raila has been lured into the belly of the beast,” said Owiti, who is still seething with anger. “He never seems to learn from his political mistakes. We have faithfully stuck with him through thick and thin, we have been beaten and killed on his behalf, we have sacrificed time and money as we gave him our unfettered support, only for him to go and shake the devil’s hand. Is Raila now telling us that it is okay for the votes that we usually give him to be perpetually stolen and do nothing about it?” posed Owiti. He told me he would never vote again – not for Raila, not for any politician.

On a more sober and practical note, Otieno Ombok, a peace and conflict resolution practitioner, told me that western Kenya had been hit with hard economic times since August 2017 and that the pact between Raila and Uhuru was necessary to revive the economy there. “I was in Siaya County in the festive month of December and believe it or not, there are homes that did not have food even on Christmas Day. Five months of street demonstrations had meant that there were no meaningful economic activities that took place since the contested August 8 elections.”

“Raila has been lured into the belly of the beast,” said Owiti, who is still seething with anger. “He never seems to learn from his political mistakes. We have faithfully stuck with him through thick and thin, we have been beaten and killed on his behalf, we have sacrificed time and money as we gave him our unfettered support, only for him to go and shake the devil’s hand.”

Something else had taken a turn for the worse: “When NASA called for the economic boycott on Bidco Oil, Brookside Dairy and Safaricom companies, Safaricom kiosks selling airtime cards and accessories closed shop in the whole of western Kenya; the little income generated by these retail trading was no more,” said Ombok. “Coupled with a ‘resist’ mood that had pervaded the region, especially in the Luo counties of Kisumu, Migori and Siaya, the people were in for real economic hard times.” Around this time, Luo youth brought down two Safaricom masts in Migori County in November 2017, an incident that was not reported in the mainstream media. “Despite threatening economic meltdown in their own counties, the youth, who were ready for more destruction and war, had no choice but to welcome the handshake,” pointed out Ombok.

A security expert working in the Office of the President, who cannot be named because of the nature and sensitivity of his work and because he is not authorised to speak to journalists, told me: “What we saw on March 9 … is quintessential Raila. In 1997, after he ran for the presidential seat for the first time and came fourth on an NDP ticket, he formed an alliance with the ruling party KANU. He collapsed NDP, joined KANU, became its powerful Secretary-General and was even made a powerful Minister of Roads. After the 2007 general elections, which resulted in post-election violence, and after many people were killed, Raila, in a much publicised truce, shook hands with Mwai Kibaki and was made a Prime Minister, albeit a non-executive one. Now he has again shaken hands with Uhuru. In all three instances, the ruling elite have understood one overriding logic: Raila is better off peeing outside from inside, rather than peeing inside from outside.”