January 30th 2018 enters Kenya’s history books alongside September 1st 2017, the day when, for the first time, an election in the country was nullified. Many dismissed the opposition coalition NASA’s threat to swear in the principals Raila Odinga and his deputy Kalonzo Musyoka as a PR gimmick.

Yet, as the new year rolled in, the momentum for the “swearing-in” gained traction within the NASA ranks and it became apparent that the “ tunaapisha movement” had prevailed over the moderates. The new concern became the possibility of a violent clash between the security forces and opposition hardliners.

On the morning of 30th January, Nairobi had a cloud of unease hovering over it. Uhuru Park was buzzing as early as 4am and waves and waves of humanity swept into the park despite the open threat of repercussions from security authorities. Doomsayers predicted a bloodbath; it was expected that there would be violence as opposition supporters faced the state’s fire power.

The day fell on a Tuesday at the end of the frugal month of January. The usual end-of-month buoyant mood displayed by salaried workers making up for weeks of being broke was absent. I encountered no traffic as I drove to meet a business prospect in the Lavington shopping centre at about 8 in the morning. On my way into the mall, I said hello to a security guard, a familiar face, and asked him why he was not at Uhuru Park. “We don’t have the luxury of demonstrating. You will be quickly sacked and replaced here”, he answered with a trace of annoyance in his voice.

The crowd at Uhuru Park had reached proportions that appeared to rival the swearing-in ceremony of Mwai Kibaki as president in 2002. You could throw a bead in the air and it would struggle to hit the ground. But there was no way in hell that a ceremony of this nature, the first in Kenya’s history, would go down without any drama.

As my business prospect and I sat down for tea, an elderly Caucasian male walked past, chatting to the mall’s security guards with the ease of a regular and teased them, “Hurry up guys, I have to be in Uhuru Park before seats run out.” There was a mix of excitement or dread in the air, depending on what side of the political divide one stood. A ruckus interrupted our conversation. The noise of loud whistles and raised voices filtered through to where we were seated. My guest worried about his car. “I hope these guys have not started rioting. I should have parked in the basement”.

A gang of five men came into sight, walking boisterously past a line of taxis with their drivers standing alert. The undertones of aggression were not reassuring. Three military Land Cruisers had driven past James Gichuru road, pressing our anxiety buttons.

The ceremony

An hour later, I returned home to monitor the live broadcast on TV. The crowds had swelled to proportions I had never seen before. With some relief, I noted that the police were out of sight and the procession to Uhuru Park was peaceful, though the city remained edgy. I got frantic calls from my relatives in the village asking whether we were okay. As a media guy I received the recurring questions: “What do you think is going to happen? Will they kill people?” I hoped for the best as I mentally prepared for the worst.

The crowd at Uhuru Park had reached proportions that appeared to rival the swearing-in ceremony of Mwai Kibaki as president in 2002. You could throw a bead in the air and it would struggle to hit the ground. But there was no way in hell that a ceremony of this nature, the first in Kenya’s history, would go down without any drama. At around noon, the government switched off the live broadcast, starting with Citizen, Inooro and NTV and then followed by KTN, which continued to broadcast for a stretch longer before it was also rendered off-air. Kenyans switched to online streaming. The media blackout only helped in heightening tensions. At Uhuru Park, the atmosphere was electric, the sea of humanity estimated to be in the hundreds of thousands patiently waiting for the man of the moment. The “swearing-in” was running late and by 1pm none of the principals had arrived.

The casualness of the whole affair was comically deceptive. An opposition leader had just sworn himself in as “The People’s President” less than three months after the constitutionally elected President was sworn in, smack in the middle of the city in broad daylight.

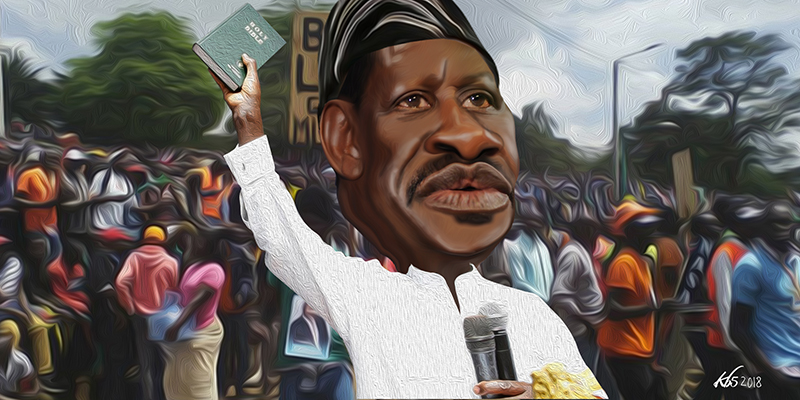

Raila Odinga finally arrived to a tumultuous welcome after 2pm. His co-principals, Kalonzo Musyoka, Musalia Mudavadi and Moses Wetangula, were nowhere in sight. Mombasa Governor “Sultan” Hassan Joho, James Orengo and T.J. Kajwang were in ceremonial dress ready to administer the oath. The lawyer Miguna Miguna and businessman Jimmy Wanjigi were conspicuously defiant. At about 2.45 pm, Raila raised a green Bible and read the oath swearing himself in as “The People’s President”. The applause reverberated throughout the city. He delivered a short and hurried speech in Kiswahili, trying to explain the absence of his co-principals and then switched to English, giving an even shorter remark and closing with the solidarity slogan, “A people united can never be defeated”. The speech lasted barely 5 minutes. He then swiftly exited the platform.

A sense of flatness descended soon after, anti-climatic in some respects, because the masses gathered at Uhuru Park had hoped that the moment’s significance would be immediately tangible. The crowds dissolved peacefully within the next two hours. The self-policed gathering appeared innately alive to the fact that any type of violent behaviour would have soiled the occasion, fueling the narrative of opposition supporters’ appetite for violence and destruction. The peaceful assembly cast the police as the provocateurs.

The casualness of the whole affair was comically deceptive. An opposition leader had just sworn himself in as “The People’s President” less than three months after the constitutionally elected President was sworn in, smack in the middle of the city in broad daylight. Uhuru Park, with its heavy symbolism of a monument of liberation movements, is just a 100 metres away from the Parliament building, the seat of Kenya’s power, and less than 200m from State House, the president’s residence. The possibility of riotous masses in their hundreds of thousands storming either State House or the Parliament in Kenya’s own version of a people’s coup was not far-fetched.

The “swearing-in” ceremony, caricatured as a farce and a self-defeatist move by its critics, achieved its aim in the eyes of the proponents of secession and the People’s Republic. Kenya now had two “presidents”, each to his own, and putting Kenya in an unprecedented political stalemate. The move was unconstitutional and even treasonable, as former Attorney General Githu Muigai had boldly stated, yet for the millions of NASA supporters it became a cathartic moment. They had scored and sent a loud and clear message that the Jubilee government was illegitimate and that their leadership was an imposition that they would not stop contesting.

Raila Odinga’s disobedience and resistance was a shot in the arm of a disenfranchised opposition that had lost complete faith in acquiring any sort of electoral justice under the present state of affairs. The growing ranks of radicals appeared to be in control of the opposition’s momentum, led from the front by economist and NASA strategist David Ndii and Miguna Miguna, the self-styled “general” of the National Resistance Movement. On December 9th 2017, after his release from police custody, David Ndii had stated his position clearly: “If the Jubilee administration decides to go extra-legal then there is absolutely nothing law-abiding people can do if their government goes rogue. It becomes the responsibility of citizens to see how they navigate themselves out of a situation where the state is captured by a rogue regime and that’s why we have constituted the People’s Assembly”.

The January 30th swearing-in was about common people, the hoi polloi asserting their presence in a highly visible manner. One barman at a restaurant I frequent told me that it was no longer about Raila Odinga; he was a symbol of resistance who everyone respected, but if Raila had hesitated to swear himself in, his supporters would have installed him as their leader anyway.

Raila, lived up to his moniker, Agwambo (the unpredictable), conquering the fear of his own political death in a transcendental moment. Courage is what the millions of supporters demanded of their leader and he stood a man apart from his co-principals who succumbed to the pressure of the moment much to the disgust of their core bases in Ukambani and Luhyaland.

The “swearing-in” reinforced Raila’s status as untouchable. The word on the street was “touch Raila and the country burns”. Raila has (not yet) suffered the fate of other opposition leaders who have dared to question the legitimacy of a sitting government in this brazen manner. The other African opposition leaders who had sworn themselves in, namely, Kizza Besiyge, Mashoud Abiola and Etienne Tshesekedi, were promptly bundled into jail. In the Kenyan political game of thrones, Raila is better in the field than out of the play, good for business so to speak. During the opposition boycott of the October 26th election, Raila’s absence on the ballot box was blamed for the low turnout in Jubilee strongholds, bringing credence to the rumours that Jubilee voters do not necessarily vote for the party but rather against Raila, the perennial bogeyman in Central Kenya.

What next?

But the question remains, what next? Soon after the ceremony at Uhuru Park, Ruaraka MP T.J. Kajwang was temporarily arrested for his role in the “swearing-in”. This was followed by the dramatic arrest, court run-around and eventual deportation of Miguna Miguna. These actions and the consequent disregard for court orders were signs of a government flexing muscle and saving face as it confronted challenges to its legitimacy.

The January 30th swearing-in was about common people, the hoi polloi asserting their presence in a highly visible manner. One barman at a restaurant I frequent told me that it was no longer about Raila Odinga; he was a symbol of resistance who everyone respected, but if Raila had hesitated to swear himself in, his supporters would have installed him as their leader anyway.

The several ordinary Kenyans I spoke to as I sought to guage the pulse of the nation all alluded to the fact that Kenya had crossed the red line of public cynicism about its politics. The political elites were completely divorced from the suffering of the masses. Life was hard for everyone no matter who you voted for.

This honour seems incomprehensible to the elite; it is easier to diminish protestors as thugs, militia or brainwashed and ignorant adherents of opposition politics. But the nature of any resistance movement changes when its followers are no longer afraid of death.

There was also a sense of hopelessness about changing the system through legal means because the rules were regularly flouted to cater to the interests of the political elite. The public had decided it was pointless to talk about democracy where rules were made to be broken.

Meanwhile, Western countries who had championed democratic reforms in the past discredited themselves by taking a unified stand to remain mum on illegalities raised during the nullified election of August 8th. During press briefings, the face of the diplomatic corp, US ambassador Bob Godec, harped on about peace in place of justice, stability in place of protest and a return to normalcy, which is the euphemism for a return to the established status quo. The West lost moral credibility after the rise of Trump, Brexit and France’s failure to face up to racism within its borders. The open bias of Western media around issues of electoral injustice has established that Kenya can no longer rely on the West for help. The fallacy of a hollow democracy for Africans where hard questions are discouraged could no longer hold.

Something else had changed. People were not afraid to die for this new ideal they believed in. According to a Standard newspaper article published on the 3rd of January, NASA supporters were planning funerals for the living as a precautionary action before any demonstration. One interviewee was quoted saying, “I do not know if it is my turn today but I beseech you my friends when I go down, do not let the ground that has fed on millions of bodies feast on mine in Lang’ata [cemetery]. Send me off with honour.”

This honour seems incomprehensible to the elite; it is easier to diminish protestors as thugs, militia or brainwashed and ignorant adherents of opposition politics. But the nature of any resistance movement changes when its followers are no longer afraid of death. The reality of the lives of millions of struggling Kenyans locked in informal settlements or in neglected villages leaves no room for fence-sitting. It matters not whether one is innocent or guilty; innocent people have been killed in their homes and children have been shot while playing on balconies. These repeated encounters with police brutality have turned many people living in the slums of Nairobi and other parts of the country into die-hard protestors.

Commentator John Lauritis wrote a piece titled “All Cops are Bad”, elaborating on how modern police institutions negate moral responsibility. He explains how the French policing model, Gendarmes, spread during the early 1800s as Napoleon Bonaparte conquered much of Europe. Modern police institutions have become a publicly-funded centralised police organised in a military hierarchy and under the control of the state. The police service was not designed to serve the public but rather to protect the political power of the ruling elite. As opposed to a community service, they have become the harsh arm of state authority. Structurally, the policing culture in Kenya that was developed in the colonial state deprives the police of moral agency and hence no cop is held responsible for individual excesses. By its very nature, the police become an agent of state impunity that is accountable to no one.

There is a sense on the ground that the only way to draw attention to the plight of the victims is to plunge Kenya into a crisis – the only language that the political elite responds to. There is an African proverb that aptly captures the mood: “If the youth are not initiated into the village, they will burn it down just to feel its warmth.”

During the September 2017 demonstrations against Independent Electoral Boundary Commission (IEBC) officials, protestors in Kisumu reprimanded the police for showing restraint and demanded the use of tear gas to disperse them. Beyond the comical undertones of that stance, protestors daring police violence has become a way of reclaiming moral authority against the police’s monopoly of violence.

Political tensions have been bubbling since the murder of IEBC ICT manager Chris Musando a week before the 8th August election. The tribally-profiled victims of state-sanctioned violence, including opposition demonstrators, have joined a long list of martyrs. There is a sense on the ground that the only way to draw attention to the plight of the victims is to plunge Kenya into a crisis – the only language that the political elite responds to. There is an African proverb that aptly captures the mood: “If the youth are not initiated into the village, they will burn it down just to feel its warmth.”

The trigger, as it appears, could be the most random action that unleashes the bottled-up frustrations of millions of Kenyans who are not prepared to wait another five years for change. The trigger of the Rwandan genocide was the shooting down of the plane carrying President Juvénal Habyarimana on April 6th 1994. The Berlin Wall collapsed on 9th November 1989 after the first secretary of the German Democratic Republic’s Central Committee, Gunter Schabowski, blundered in a speech that was broadcast to the world. Before the speech could be retracted, East Berliners had gathered at the wall, overwhelming the border security. The self-immolation of street hawker, Mohammed Bouazizi, after he had been harassed by the police, was the trigger that brought down President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali’s 23-year hold on the Tunisian people. Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe was brought down by a speech given by his wife “Gucci” Grace Mugabe that led to the expulsion of former Vice President Emmerson Mnangagwa from the ZANU ruling party.

History is filled with pages of ordinary people negotiating their own justice; there comes a point when oppressed masses cease to be afraid of brutal state power.

Kenya crossed a tolerance threshold on January 30th 2018. The facade of democracy and unity fell apart and Kenyans have now occupied hard-line positions, well aware of the precipitating political crisis. The crackdown on opposition leaders only adds to the narrative of a state hell-bent on providing the incentive for an inferno. The dominance of the Kikuyu and the Kalenjin in political positions engenders a victimhood complex; those who refuse to speak against the victimisation are considered to be complicit in the suffering of their fellow citizens. Oppression is the grievance that unites Kenya’s disenfranchised masses against the “two bad tribes”.

History is filled with pages of ordinary people negotiating their own justice; there comes a point when oppressed masses cease to be afraid of brutal state power.

The great unwashed are restless. The Kenya Project is rushing to a tipping point. “[When] things fall apart; the centre cannot hold,” wrote the Irish poet W.B. Yeats.

In the interim, we return to our perpetual state of angst, as if living next to a haunted swamp that keeps bubbling. There is evidence that something lurks. The weather just needs to change and the soul is seized again.