Zimbabwe has a new president thanks to what its military chiefs called an “intervention” to “weed out criminals” that were negatively affecting the work of the President. The actions of the army generals ended up leading to a popularly, if not emotionally, supported removal of President Mugabe, the man they had initially pledged to be acting to protect.

The new president, Emmerson Mnangagwa was sworn in on Friday 24 November 2017. The state media glowingly called it an inauguration at Harare’s National Sports Stadium at a ceremony attended by at least 60,000 people, including serving presidents from the Southern African Development Community (SADC) member states, Ian Khama, Edgar Lungu and Filipe Nyusi of Botswana, Zambia and Mozambique respectively.

There are multiple reasons why the army and those sympathetic to the ruling party within SADC would not out rightly call the tumultuous political events in Zimbabwe over the last two weeks a coup. Or why the commander of the Zimbabwe Defence Forces (ZDF) General Constantino Chiwenga and his subordinates would reach such alarming levels of national popularity.

The most obvious reason is that a lot of people in Zimbabwe, the region and the continent were genuinely tired or annoyed by Mugabe’s long stay in power. His wife most certainly did not help matters in a patriarchal society by insulting those who were long time loyalists (including Mnangagwa) in public. The move by the military, well-choreographed as it was, invariably had a popular veneer to gloss over what it really was, a decision by the military to defy their commander in chief and hold him in captivity. Also generally known in political science studies as a military coup d’etat.

There are multiple reasons why the army and those sympathetic to the ruling party within SADC would not out rightly call the tumultuous political events in Zimbabwe over the last two weeks a coup. Or why the commander of the Zimbabwe Defence Forces (ZDF) General Constantino Chiwenga and his subordinates would reach such alarming levels of national popularity.

The other more significant motivation for the military intervention is that the ruling ZANU-PF party had failed to deal with its succession politics via the clearer political route. And that the veterans of Zimbabwe’s liberation guerilla war which run from the late 1960s to 1979 and who are recognized in the national as well as the ruling party constitutions, were beginning to stake a claim on who they thought should succeed Mugabe. Initially, and this is to their credit, the Zimbabwe National Liberation War Veterans Association (ZNLWVA) sought the political route to resolving this issue. They were the only members of the ruling ZANU-PF party that consistently asked Mugabe to appoint his successor, much to the latter’s chagrin. Mugabe would insist that his successor would come from the people via congress and that it was only the people who would tell him to go.

The decisive factor to consider, therefore, is how the war veterans eventually got to the stage where their preferred successor, Emmerson Mnangagwa, got fired and made what is with hindsight a startlingly prescient claim as he left for exile in South Africa that he would be back to lead Zimbabwe. He would also cheekily refuse to meet Mugabe before the latter resigned because the ‘people have said so’.

The war veterans are not only former guerrillas in Zimbabwe’s liberation war. They are also still serving in key command positions in all sections of the National Army, the Police Service, the Airforce and the Prisons Services. The commander of the ZDF, General Chiwenga is himself a war veteran, and so are all of his subordinates.

In the corridors of the ZNLWVA, it is an open secret that the veterans felt it was the turn of one of their own, or at least one who had undergone military training during the war to take over. This, it was argued by some of the war veterans leaders, was because the nationalists (such as Mugabe, Joshua Nkomo and others) had had their turn at the head of the liberation movement and, more significantly in Mugabe’s case, as head of state and government.

Their consistent argument was that as a liberation movement, due recognition should be given to those that went to war but are still alive and still capable of playing a leadership role in the post-independence ruling ZANU-PF party and its government. And quite literally, this role meant having ‘one of their own’ being the first secretary and president of the ruling ZANU-PF party. (Mnangagwa is viewed as exactly that by the war veterans.)

And that the veterans of Zimbabwe’s liberation guerilla war which run from the late 1960s to 1979 and who are recognized in the national as well as the ruling party constitutions, were beginning to stake a claim on who they thought should succeed Mugabe.

Zimbabwe’s military is therefore led by those that were and are part of ZANU-PF in two specific respects. First as a liberation movement and secondly as a contemporary ruling party. It is also important to note that unless they have been unwell, all service chiefs, including the commander of the ZDF, have religiously attended, the ruling ZANU-PF party’s annual conferences and periodic congresses.

Though they will claim neutrality in politics, their actions clearly indicate that the military top brass is embedded in the liberation struggle claim of being the military wing of what once was a revolutionary movement prior to independence.

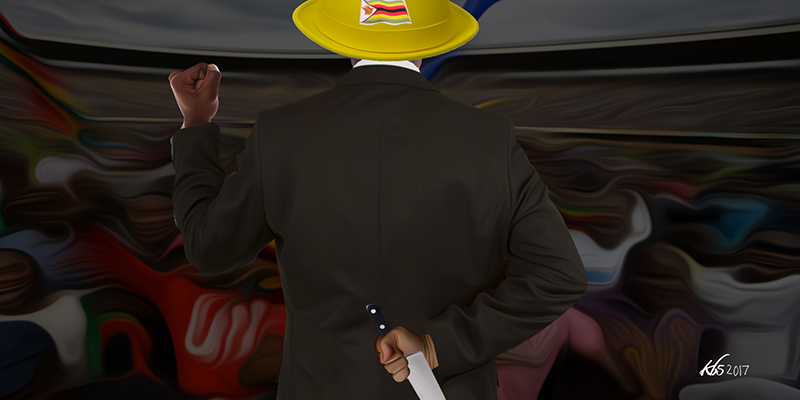

When Mugabe used to claim that his party had committed itself to the Maoist dictum that it is ‘politics that always leads the gun’, he probably assumed that those holding the gun had no vested interests. Nor thought that they could carry out an internally (to the party) and externally (nationally) popular coup.

They did this using a combination of understanding national constitutional and internal ruling party processes and procedures, knowing the then first lady Grace Mugabe’s lack of popularity, and reaching out through cultural events/music to younger Zimbabweans. (There is a popular musical outfit called Military Touch Movement that, as its name suggests, is rumoured to have close ties to the military establishment).

On the national party processes and procedures, they knew that SADC would never accept anything that they referred to as a coup. Their carefully choreographed public statements – referring to Mugabe as being confined to his home, and as still being in charge of the country while allowing him to appear at a graduation ceremony and undertake a “State of the Nation” address where he conceded that their actions had his permission – were testament to that. Allowing and urging Zimbabweans, through the ZNLWVA to march on the capital’s streets and closely controlling the domestic media narrative, the veterans managed to get the American and British governments to support their cause through issuing positive statements even as SADC dithered.

The subsequent roping in of the ZANU-PF Central committee to dismiss Mugabe and recommend Mnangagwa to succeed him until not only their extraordinary congress scheduled for early December 2017 but also the harmonized general elections for 2018, entrenched a civilian dimension in what was a military-led deposing of the party leader.

After it turned out Mugabe was ‘refusing’ to resign, a process of parliamentary impeachment that ZANU-PF embarked upon, ironically with the support of the mainstream opposition Movement for Democratic Change-Tsvangirai (MDC-T), sanitized the military change of ZANU-PF leadership.

The generals had however not stopped trying to persuade Mugabe to resign and through a mediation process facilitated by a Catholic priest, eventually got the letter they wanted on 21 November 2017 as parliament sat to impeach their Commander in chief.

When Mugabe used to claim that his party had committed itself to the Maoist dictum that it is ‘politics that always leads the gun’, he probably assumed that those holding the gun had no vested interests. Nor thought that they could carry out an internally (to the party) and externally (nationally) popular coup.

Emmerson Mnangagwa upon his return was well aware of this and made it apparent in his first remarks to his supporters at a rally held at the ZANU-PF headquarters. He however indicated that he had all along had a hand in this ‘intervention’ by staying in ‘constant touch’ with the generals even though he was in exile.

He also made it clear in his first address as president of Zimbabwe, that he owed his ascendancy to the ruling party. This is a point that the generals would have no problem with, as they were acting, in the final analysis, in tandem with their role as what General Chiwenga has referred to in previous interviews with the state media as ‘stockholders’ of the liberation struggle and therefore the country. All via the party.

SADC could do little else. Not least because of the fact that apart from Malawi, Zambia, Seychelles and Mauritius, all of the current governments in the region are led by former liberation movements (Kabila’s in the DRC claims Lumumbist origins to his government). And they tolerated this military action on a serving president so long there was deference to the ruling party and a modicum of constitutionalism could be salvaged from the process.

For now, with Mnangagwa sworn in as a president to finish off Mugabe’s term as outlined in the sixth schedule of Zimbabwe’s constitution, this would appear to be the case. I am certain that SADC will probably follow up with the new president on the holding of free and fair elections in 2018 as scheduled, which Mnangagwa confirmed in his first speech as president and when he will pursue a full five-year term.

This is not to say ZANU-PF’s military-political complex does not understand the need for ‘performance legitimacy’ despite having the capacity to deploy force for a political outcome. They understand this entirely hence Mnangagwa’s new focus is on the national economy.

SADC will definitively seek a greater role in supervising these elections and closely monitor the role of the military in how they are conducted. But the ruling party will not worry too much about this as it is already riding on a peculiar wave of popularity that while it is surprised by, it is still very keen to consolidate, not only to renew its stay in power, but also to make it unthinkable for the opposition MDC-T, or any new opposition parties for that matter, to realistically hope to wrestle away power. Also, because the war veterans actively serving in the defence forces have become the guarantors of the ruling party’s succession politics and its ability to stay in power at a time of political crisis.

This is not to say ZANU-PF’s military-political complex does not understand the need for ‘performance legitimacy’ despite having the capacity to deploy force for a political outcome. They understand this entirely hence Mnangagwa’s new focus is on the national economy. His government intends to introduce free market economic policies and probably do so within the ambit of Chinese-style ‘state capitalism’ which will court foreign direct investment and introduce property rights to the controversial issue of the Fast Track Land Reform Programme (FTLRP).

One of the first acts of his government will be to ease the liquidity crisis and seek the effecting of what Mugabe had referred to as ‘mega deals’ with the Russians and the Chinese in order to create a massive influx of jobs. The American and British governments will be courted to invest in the economy in return for the removal of sanctions and the re-integration of Zimbabwe into Western investor circles. And the Australian government will get promises to protect its mining interests again in return for support in other areas of the national economy.

What is apparent is that in the aftermath of this military intervention, there is limited scope for a value based politics in Zimbabwe. The now very popular actions of the ZDF in tandem with the political endorsements of ZANU-PF have left a void that the opposition cannot fill.

While this temporary and highly politicized economic shift is underway, the opposition will be courted with carrots such as support for the livelihoods of some of its leaders along with deferential treatment. But essentially, they will be a divided lot that will be unable, barring a miracle, to defeat Mnangagwa’s militarized but popular version of ZANU-PF in what the latter will be at pains to prove to SADC, the African union and the world, is a free and fair 2018 election.

What is apparent is that in the aftermath of this military intervention, there is limited scope for a value based politics in Zimbabwe. The now very popular actions of the ZDF in tandem with the political endorsements of ZANU-PF have left a void that the opposition cannot fill. That void is the inability to articulate what would have been a democratic alternative to ZANU-PF rule, especially given the backing of war veterans in the military and the neo-liberal global west and east in their pursuit of markets, minerals and military dominance.

As it is Zimbabweans must brace themselves to be governed by a military–political complex that claims legitimacy on the basis of national liberation and assumes it can re-create itself in subsequent generations of not only civilians, but also those that would serve in the defence forces. All in aid of an intended perpetuation of ZANU-PF’s hold on political power and the cosmetic maintenance of a hapless and long suffering political opposition.