During a transition into a new presidential tenure such as Kenya is going through at this point in 2017, it is expected that people – certainly government and governance scholars – will review the outgoing tenure so as to highlight the needs of the incoming tenure. If such reviews become a habit, then the next logical step is to review the comparative performances of presidents and/or presidencies over the years, with a view to assessing aspirants for suitability.

The mutations to the independence gave much power to the Executive relative to the Legislature and Judiciary: all public servants were employed “during the pleasure of the President”, which bred extensive impunity in the upper echelons of the Executive. That the reformist 2010 Constitution, designed to put paid to such potential Executive excess, has failed to do so reflects, inter alia, the depths to which the roots of impunity had sunk during the initial 47 years of independence.[1] That impunity is alive and well in and around the presidency, is elaborately manifest even in the persisting illegalities and irregularities surrounding the transition to a new presidential tenure. This is an indicator of the nature of disposition to constitutionalism.

The global literature illustrates varied approaches to evaluating presidents and/or presidencies, such as through the analyses of speech content, performance of the economy, and opinion poll ratings, amongst others. These listed approaches are more amenable to the evaluation of developed country contexts where such data is habitually gathered; but this is not the case for developing country contexts, such as Kenya. For the latter countries, presidential speeches are based on opportunistic political expediency rather than on the individual’s beliefs; economies are disproportionately driven by exogenous rather than endogenous factors; and opinion polls are excessively subjective. However, a useful yardstick with which to compare president or presidencies is fidelity to the constitution of the day, which is supposed to be the social contract with the citizens of the country. Given the respective contexts within which Kenya’s independence and 2010 constitutions were made, it is reasonable to expect greater fidelity to the latter which arguably carries greater legitimacy.

However, a useful yardstick with which to compare president or presidencies is fidelity to the constitution of the day, which is supposed to be the social contract with the citizens of the country.

The making of Kenya’s independence constitution was chaperoned by the British, with delegates from the colony abiding by the tradition of attending talks at Lancaster House in London. Despite the British government’s declared ‘wind of change’ sweeping in independence for its colonies, its kith in Kenya, the White settlers, briefly contemplated a ‘unilateral declaration of independence’, which would have perpetuated the relative voiceless-ness of the majority African population.[2] But the Africans at the constitutional talks did not also speak with one voice: the self-serving settlers had successfully heightened the fears of the Africans from the smaller ethnic groups under the Kenya African Democratic Union (KADU) party, of domination by those from the two largest groups, the Kikuyu and Luo, who were grouped in the Kenya African National Union (KANU) party. Thus, broadly speaking, the independence constitution was the product of compromise among four delegations, rather than one between a united African front and the colonizer, Britain. In contrast, the making of the 2010 Constitution was a ‘people-driven’ comprehensive review process commenced in 1999, with a large number of delegates, 629 in total, attending the National Constitutional Conference at the Bomas of Kenya venue.

A dominant feature of Kenya’s 27 constitutional changes between 1963 and 2008 was the centralization of power in the Executive, specifically on the President. Founding Prime Minister Jomo Kenyatta – hereafter Kenyatta I – begun the cannibalization of the independence constitution as early as 1964, when he declared himself the President of the Republic of Kenya. The other 1964 changes also watered down the independence of regional governments, which were consequently killed in the next year. The 1966 changes ushered in dictatorship, amalgamating the Senate and National Assembly,[3] derogating rights and freedoms while also introducing detention without trial. Furthermore, 1966 saw the constitutional stifling of the Kenya People’s Union (KPU) opposition party launched in 1965 and gave the President power to hire and fire all in the public service, while 1968 saw the abolition of independent candidates and provided for the President to be elected through a General Election, as opposed to election by the National Assembly, which made him politically independent of the latter. By 1969, the President had acquired the right to appoint the Electoral Commission of Kenya; but the need to rationalize these multiple amendments led to ‘rebasing’ the constitution on that year. Among the last of Kenyatta’s 15-odd amendments would be one to allow him to pardon ex-Kapenguria detainee, Paul Ngei, and allow him to return to politics after he was convicted of an electoral offence.

Thus, broadly speaking, the independence constitution was the product of compromise among four delegations, rather than one between a united African front and the colonizer, Britain.

Among the more outstanding constitutional amendments of successor president Daniel Moi (1978-2002), was the infamous Article 2A of 1982, transforming the country into a de jure – by law – single party state that made KANU the Baba na Mama of all Kenyans. Another outstanding amendment was the 1991 repeal of the same Article 2A, which returned the country to multipartyism.[4] In between, 1986 witnessed the mischievous removal of security of tenure for the Attorney General and the Auditor and Controller General (CAG), and the increase of parliamentary constituencies to 188. Torture was allowed in 1987, while security of tenure for constitutional offices was removed in 1988. Security of tenure returned in 1990 amidst pressure for the opening up of democratic space for Kenyans; and in 1991 constituencies increased to 210.

While these constitutional gymnastics suggested regimes that were keen to be on the right side of the ‘mother law’, there was extensive repression in other realms, such as the 1980s onslaught against real or imagined Mwakenya and Pambana activists. The treatment of suspects, with several prosecutors and magistrates acting as the system’s hatchet men, was in violation of the well-known and internationally accepted rights of people in such circumstances. And of course, there were several assassinations, among the better known ones being Pio Gama Pinto, Tom Mboya, J.M.Kariuki and Robert Ouko. The era saw many unexplained accidents, disappearances and extra-judicial killings. Additionally, individuals were ‘dealt with’ through various other means, such as a vocal Assistant Minister being imprisoned for violating foreign exchange regulations by inadvertently keeping some loose change after foreign trips.

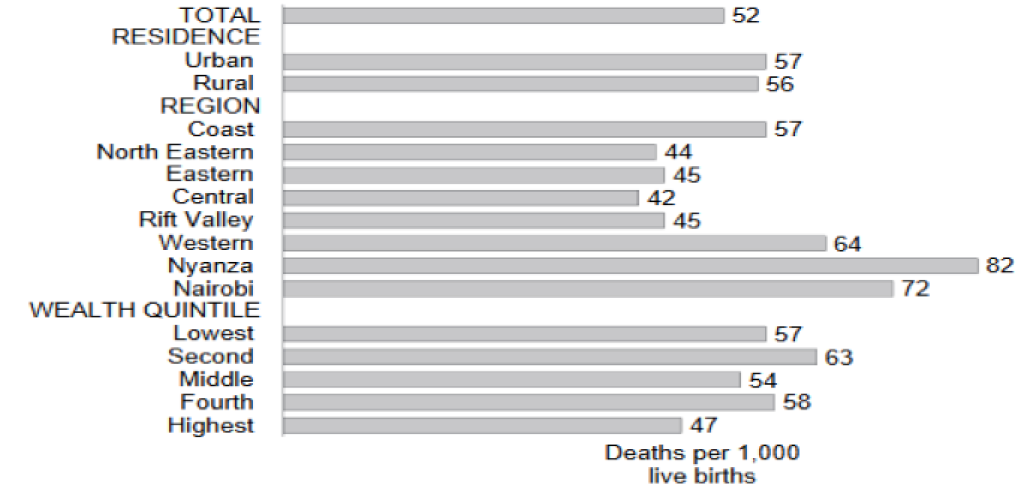

The independence development blueprint, Sessional Paper No. 10 of 1965 on African Socialism, had provided that scarce investment resources would be focused on “areas of greatest absorptive capacity”, with surpluses being redistributed to the lower absorption parts of the country.[5] Growth occurred in fits and starts,[6] but there was little redistribution to the low absorption regions and communities previously overlooked by colonialism.[7] Instead, there was expropriation through harambee fund-raising for social sector investments even as the government extensively biased budget resource allocations. Thus, for example, public health care resources went disproportionately to the parts of the country that had a harambee capacity to build health facilities, rather than to those parts that had comparatively greater disease burdens, such as the malaria endemic regions. The net effect of such inequitable resource allocation have been the inequalities in health status, such as are reflected in the child mortality rates of Figure 1.[8]

Figure 1: Under-5 Mortality Rates by background characteristics, 2014

Source: KDHS, 2014

The illustration above of disregard for comparative development needs was given further impetus by both regimes’ resort to parochialism – and indeed, nepotism – in key public appointments. Notwithstanding public employment being “during the pleasure of the President”, it is difficult to imagine that any tenant of State House believed that the national interest was best served through excessively parochial public appointments. Table 1 shows that belonging to the president’s ethnic group was significant for the distribution of cabinet positions, with ethnic shares fluctuating markedly depending on the president’s ethnicity. And beyond merely having a cabinet position, ethnicity also determined which lucrative dockets went to whom. Such exalted positions enabled the illegal but unpunished diversion of Parliament-sanctioned development resources away from areas perceived hostile to the government to ‘politically-correct’ areas. The context also enabled self-aggrandisement with impunity since such individuals’ closeness to the president protected against prosecution.[9] In any case, the annual CAG reports that would highlight such criminal misconduct would be several years behind schedule, complicating remedial action.[10]

Table 2: Ethnic shares of Kenyan cabinet positions and population (%)

| Ethnic group | Kenyatta (Kikuyu) | Moi (Kalenjin) | Kibaki (Kikuyu) | Share of population | ||||

| 1966 | 1978 | 1979 | 2001 | 2003 | 2005 | 2011 | 2009 | |

| Kikuyu | 28.6 | 28.6 | 30 | 4 | 16 | 18.1 | 19.5 | 17 |

| Luhya | 9.5 | 4.8 | 11 | 14 | 16 | 21.2 | 17.1 | 14 |

| Luo | 14.3 | 14.3 | 11 | 7 | 16 | 3.1 | 12.2 | 12 |

| Kalenjin | 4.8 | 4.8 | 11 | 17 | 7 | 6.1 | 9.8 | 13 |

| Total | 21 | 21 | 26 | 28 | 25 | 33 | 42 | – |

The ad hoc reviews of the constitution led to internal contradictions; but weak fidelity to the letter of the document also opened up further opportunities for impunity. For example, the dividing line between KANU and the Executive increasingly became blurred over policy-making and implementation; and the context increasingly dictated the agendas of the Judiciary and Parliament. As reflected in the 1988 queue voting – mlolongo – exercise, democratic electioneering lost meaning: in instances, the shortest queue of supporters would be declared victorious. These contradictions led to extensive demands for a comprehensive review of the constitution in the run-up to the 1997 general elections. The brutal response of the government was most vividly captured in the police invasion of the inner sanctum of the All Saints Cathedral into which they lobbed tear gas against demonstrators. The stand-off was eventually resolved through the Inter-Parties Parliamentary Group (IPPG) process, which was able to extract modest reforms from the government, such as the inclusion of opposition in nominating members of the electoral commission hitherto appointed exclusively by the President.[11] While Moi retained power at the election, the seed of change had been sown;[12] sustained internal and external pressure for a comprehensive constitutional review led to the Bomas of Kenya conference launched in 2003.[13]

While these constitutional gymnastics suggested regimes that were keen to be on the right side of the ‘mother law’, there was extensive repression in other realms, such as the 1980s onslaught against real or imagined Mwakenya and Pambana activists.

The shenanigans around the constitution review process are well documented: suffice it to say that it took 10 years of back and forth, and critically, over 1,300-odd deaths and half-a-million internal displacements during the 2007/08 post-election violence, to focus the government on the delivery of a new constitution.

IPPG had not convinced Moi of the need for comprehensive change; so he had set about co-opting perceived ethnic chiefs into KANU to diffuse the growing clamour for an end to Nyayoism. In a perverse way, that Moi strategy probably made a major contribution to liberating Kenya from his clutches, even if his empire would later strike back. Moi’s strategy culminated in the Kasarani Stadium conference at which he declared a comparative political nonentity, Uhuru Kenyatta, to be his heir.[14] That action sparked a revolt that passed through various political outfits to coalesce in the exceedingly ethnically broad-based and popular National Alliance Rainbow Coalition (NARC) party. This was the party that brought Kibaki to the presidency in 2003, with a promise of a new constitution in 100 days.

Yet if the promised NARC revolution had got rid of Moi and his preferred heir, Kenyans would soon realise that Moi-ism – the disregard for constitutional, policy and legal frameworks – had merely acquired a new face; and there were hints of a reinvention of the autocracy of Kenyatta I. Of the ‘new constitution within a 100 days’, a leading Kibaki ally would declare that there had been nothing wrong with the existing constitution, and that changes to it had only been desired as a means of getting rid of Moi. The growing indiscretions of the Kibaki faction in NARC meant that the party soon imploded,[15] even as that faction set about manipulating the Bomas Draft Constitution to perpetuate the status quo. These divisions set the stage for the 2005 national referendum defeat of Kibaki’s preferred version of the proposed constitution, which in turn set Kenya on the road to the disputed 2007 presidential elections, and the violence the followed in its wake.[16]

As reflected in the 1988 queue voting – mlolongo – exercise, democratic electioneering lost meaning: in instances, the shortest queue of supporters would be declared victorious.

Notwithstanding the unprecedented horror surrounding it, the 2007-08 post-election violence had a silver lining: its resolution by the Kofi Anna-led African Union’s Panel of Eminent Personalities led to, amongst other things, the institution of Agenda Item 4 of 2008 – the basis of long term governance reforms in the country.[17] A newly independent African country’s primary ambition must surely be the transformation of the state (constitution), boundaries and peoples into a nation-state. One might try to explain Kenyatta I’s failures in this respect on his old age and his being overwhelmed by the very idea of ‘independence’ (self-rule); and Moi’s failure on his narrow world view that limited exposure to ideas, such as nation-hood. But neither explanation could hold for the much younger, more educated, and indeed cosmopolitan Kibaki’s failure to realise the dreams of the NARC revolution. And Kibaki’s failure to grasp the remedial opportunity provided by Agenda 4 underscored his lack of fortitude and his ethnic insularity. A president offered great opportunities proved entirely ineffectual.

So ineffectual was Kibaki that he largely seemed to have slept through the International Criminal Court (ICC) indictments of Kenyans adjudged to have had the greatest responsibility for the 2007/08 post-election violence.[18] But Kibaki did have reason to let sleeping dogs lie, even as Moreno Ocampo muddled his way through the early ICC processes: the National Intelligence Service’s (NIS) evidence to the Waki Commission was that Kibaki’s National Security Council (NSC) had been regularly briefed on people arming themselves for violence after the elections. If NSI’s evidence was true – and nobody denied it – then the NSC chair should have been first on the plane to ICC: he knew of impending violence, and failed to contain the threat despite having both the constitutional obligation and the means with which to do so.

Yet if the promised NARC revolution had got rid of Moi and his preferred heir, Kenyans would soon realise that Moi-ism – the disregard for constitutional, policy and legal frameworks – had merely acquired a new face; and there were hints of a reinvention of the autocracy of Kenyatta I.

Among the distinguishing acts of the Kibaki presidency was his rampant creation of unconstitutional administrative districts. In 1997, Kibaki’s Democratic Party had won a High Court action against President Moi for creating some 30-odd “unconstitutional districts”, which the judge did not dissolve because it was the eve of a general election premised on those very districts. Yet during his presidency, right up to the 2010 promulgation of the new constitution, Kibaki created over 200 new, similarly unconstitutional districts,[19] which the new Constitution duly abolished by transforming the constitutional 47 into counties.

Among Agenda 4’s objectives was the time-bound promulgation of a new constitution, which Kibaki hardly campaigned for ahead of the national referendum on it. That the Constitution (2010) is transformative is indisputable: while Chapter 1 of the 2008 version of the independence constitution says nothing about the people of Kenya before launching into the greatness of the President, Article 1 of Constitution (2010) conditions the presidency on the will of the people in declaring as follows:

“(1) All sovereign power belongs to the people of Kenya and shall be exercised only in accordance with this Constitution5)

(2) The people may exercise their sovereign power either directly or through their democratically elected representatives.”

Having declared as such, the Constitution (2010) further takes power away from the President in three important respects: (i) it underscores the separation of powers between the Executive, Judiciary and Legislature (Article 1(3)); (ii) instead of all public servants being employed “during the pleasure of the President”, key public offices are filled through people-driven processes as well as protected against external interference (Articles 160, 228, 229, and Chapter 13, etc); and (iii) it creates the national and county levels of government which “are distinct and inter-dependent and shall conduct their mutual relations on the basis of consultation and cooperation (Articles 6 and 189).”

Kibaki’s failure to grasp the remedial opportunity provided by Agenda 4 underscored his lack of fortitude and his ethnic insularity. A president offered great opportunities proved entirely ineffectual.

A further driver of impunity and parochialism under the independence constitution had been the central control of government resources began by Kenyatta I’s 1964 constitutional amendments that took service delivery and revenue generation functions away from the regions. However, the Constitution (2010) proved true to the principles of effective fiscal decentralization: its Fourth Schedule divided functions between the National and County Governments; and Chapter 12 on Public Finance ensures that money (resources) follows the Fourth Schedule’s division of labour.

As noted above, the Kibaki regime was not overly pleased with the governance changes occasioned by the new constitution,[20] especially devolution which would take “at least 15 percent of national revenue” out of Treasury’s control (Articles 203 (2), 207 (1) and 209).[21] This displeasure was most graphically illustrated in the stand-off over the draft Public Finance Management Bill, between devolution’s then mother ministry, Local Government, and the Finance ministry. While Treasury insisted on retaining control of monies devolved by Parliament to county governments, the Local Government prevailed with its position aligned to the recommendations of the Task Force on Devolved Government[22] and the spirit of the Constitution, that Treasury must not touch such monies. Additionally, and critically for effective transition to devolution, the Kibaki government delayed the establishment and adequate resourcing of the Transition Authority, the statutory midwife of the process. This meant that devolution was launched in April 2013, before the Authority could complete many of the preparatory measures envisaged by the Task Force on devolution, and reflected in the Authority’s founding statute.[23]

These goings-on confirm Kenyatta’s place among his predecessors’ ‘constitutionalism for convenience’: if it hampers, ditch it!

Kibaki’s 2013 succession was a somewhat messy affair. His regime had a perception that a Kikuyu could not – or at least should not – succeed him; and so it searched for an ‘acceptable’ non-Kikuyu to oppose Raila Odinga and subsequently manage the ICC burden favourably, with Finance minister Kenyatta, arguably the strongest Kikuyu presidential candidate, indicted there for the 2007/08 post-election violence. Meanwhile, Kalonzo Musyoka’s 2008 backing of Kibaki had enabled the latter to form a government despite a numerically stronger opposition; and Musyoka had reason to expect the favour to be returned. Elsewhere, Kenyatta considered a candidacy for fellow Deputy Prime Minister and former Vice President, Musalia Mudavadi, who had the additional advantage of family ties to former president Moi. In the event, Kenyatta abandoned Mudavadi, declaring “the devil” to have caused him to even think of that option, broke loose of Kibaki handlers, and joined forces with fellow ICC suspect, William Ruto, to milk their tribulations for political gain. These developments pushed Musyoka into an alliance with Odinga.

However, a summary of Kenyatta’s attitude to constitutionalism is best illustrated by his conduct during the 2017 presidential elections. Even as he laments constitutional obstacles to fighting corruption, Kenyatta consistently used state resources to curry favour among individual politicians and voters.

These goings-on confirm Kenyatta’s place among his predecessors’ ‘constitutionalism for convenience’: if it hampers, ditch it! For example, while the full implementation of the Constitution (2010) is viewed as a plausible instrument against corruption, Kenyatta has wished for the independence constitution’s imperial presidency.[24] Secondly, Kenyatta is among the Kiambu-ians who came to terms with ‘the snake crossing the River Chania’ into Nyeri,[25] but cannot countenance the snake leaving the ‘House of Mumbi’, an underlying issue in the post-2007 election agenda.[26] Additionally, after losing the 2002 presidential election, Kenyatta had become the Leader of the Opposition in Parliament, and eventual chair of the KANU party; but he would lead the party into Kibaki’s Party of National Unity coalition in the run up to the 2007 election, and eventually abandon it for his own presidential run with an eye on ensuring a House of Mumbi victory in the 2013 elections. The Supreme Court upheld Kenyatta’s victory in that election; but the court’s decision was derided by numerous legal scholars.[27]

While Kibaki seemed ambivalent during the 2010 debates on the Proposed Constitution, Kenyatta publicly supported it. However, as Finance Minister, his attitude towards the document was evident in his disregard of it over the management of devolved funds. Additional events further illustrate Kenyatta’s less than complete support for the constitution he swore to defend, such as his predilection is well known for grandiose, resource-consuming projects that have pushed the national debt burden beyond the East African Community sustainability levels. Such infrastructure priorities have paid scant attention to Chapter 4 of the Constitution’s guarantee of the right to food, clothing and shelter.

Yet, it is Kenyatta II’s failure to fully implement the transformative Constitution (2010) that stands him out as a great enemy of constitutionalism.

However, a summary of Kenyatta’s attitude to constitutionalism is best illustrated by his conduct during the 2017 presidential elections. Even as he laments constitutional obstacles to fighting corruption, Kenyatta consistently used state resources to curry favour among individual politicians and voters. Public servants and other resources were deployed to the regions to curry favour for his Jubilee party. The regime has also been notorious for its persistent arm-twisting of constitutional commissions and independent offices, most notably the Auditor General and the Controller of Budget. Disdain for the independence of such institutions was most vividly illustrated in Kenyatta’s recurrent outbursts against the Supreme Court which had nullified the August 8 elections for being fraught with “illegalities and irregularities”. Yet two of the judges Kenyatta dismissed as wakora – crooks – had upheld his 2013 election despite big questions and all would uphold his victory in the October 26 repeat election. In spite of their recruitment on constitutionally determined merit, Kenyatta would ask the same judges rhetorically: “Who even elected you?”, and would promise to ‘revisit’ and ‘fix the court ‘problem’.[28] Since then, the law has been changed to complicate the nullification of a presidential election.

Conclusions

This note has presented a broad-brush review of the relationships between Kenya’s four presidents to date and their regimes, and the constitution. The broad finding is that all the presidents have not been sticklers for the either the letter or spirit of the constitution, applying it when convenient, and amending it or even violating it when the need has arisen. Kenyatta I’s apologists might point to the context of his tenure – an autocrat in euphoria over the new independence status; and Moi’s apologists will emphasize his restricted world view. It is however, difficult to go beyond ethnic insularity find explanations for Kibaki’s failure to embed constitutionalism more deeply in governance and his misadventure which led to many lost and wasted lives and livelihoods, is an indictment he will never escape. Kenyatta II is an extension of the Kibaki heritage in many respects, having been an alleged hatchet man in the horrors of 2007/08. Yet, it is Kenyatta II’s failure to fully implement the transformative Constitution (2010) that stands him out as a great enemy of constitutionalism. Based on these experiences, the outlook for Kenyan constitutionalism looks bleak.

References

Bigsten, Arne (1977), Regional Inequality in Kenya. Nairobi, Kenya: Institute for Development Studies, University of Nairobi

Kanyinga K, Okello D. Tension and Reversals in Democratic Transitions: The Kenya 2007 General Elections. Nairobi: Society for International Development and Institute for Development Studies (IDS), University of Nairobi; 2010.

Kenya National Bureau of Statistics et al. (2014), The Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2014. Nairobi, KNBS. Available at https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/fr308/fr308.pdf

Kenya National Commission on Human Rights (2008), On the Brink of the Precipice: A Human Rights Account of Kenya’s Post‐2007 Election Violence. Nairobi: KNCHR. Available at https://kenyastockholm.files.wordpress.com/2008/08/pev-report-as-adopted-by-the-commission-for-release-on-7-august-20081.pdf

Kipkorir, Benjamin (2016), Descent from Cherang’any Hills: Memoirs of a Reluctant Academic. Moran (E.A.) Publishers Ltd.

Kivuva, Joshua M. (2011), Restructuring the Kenyan State. Constitution Working Paper Series No.1. Nairobi: Society for International Development.

Ministry of Local Government (2012), Interim Report of the Task Force on Devolved Government: A report on the implementation of Devolved Government in Kenya. Nairobi: Local Government.

Murunga, Godwin and Sharack Nasong’o (Eds.) (2013), Kenya: the struggle for democracy. London: Zed Books

Mutua, Makau (2008), Kenya’s Quest for Democracy: Taming Leviathan (Challenge and Change in African Politics). Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

URAIA Trust and IRI (2012), The Citizen Handbook: Empowering citizens through civic education. Nairobi: URAIA/IRI. At http://www.juakatiba.com/public/publication/eccbc87e4b5ce2fe28308fd9f2a7baf3.pdf

[1] That impunity persists despite the structural opportunities to fight it is also a reflection of the hopelessness of a majority of the Kenyan people, as illustrated in the rest of this note.

[2] This was precisely what the European settlers in Rhodesia did in 1965, leading to minority rule opposed by guerilla warfare in that country until formal independence was negotiated in 1980.

[3] While the constitution had provided for a multi-party state in a bi-cameral parliamentary system, the opposition KADU party was ‘encouraged’ to dissolve itself by “crossing the floor”, transforming Kenya into a de facto single party state, even if in law t remained a multi-party state

[4] After the 1969 banning of ex-Vice president Oginga Odinga’s KPU party, and the detention without trial of all its leadership, the country became a de facto single party dictatorship.

[5] The ‘higher absorption’ parts of the country were the former White Highlands of central Kenya and the spine of the Rift Valley, settled by European settler farmers, in which the colonial government had used ‘native’ tax revenues, such as is reported by Kipkorir (2016), to build development-facilitating infrastructure, such as roads, electricity and telecommunications.

[6] For example, allowing African small scale farmers to grow cash crops at independence boosted national economic growth into the late 1960s, but the oil crises of 1974 and 1979 dampened performance.

[7] See Bigsten (1977).

[8] Kenya National Bureau of Statistics et al. (2014).

[9] A local government minister, for example, used Nairobi City Council equipment to grade a road to his Kajiado home in preparation for his son’s wedding.

[10] Into the early 1990s, these annual reports were 7 years behind schedule, meaning the responsible officer had likely transferred, retired, or indeed, died.

[11] See Murunga and Nasongo (2013).

[12] Even Mwai Kibaki who a decade earlier had declared that removing Moi and KANU from was like trying to cut down a mugumo tree using a razor blade, ventured to contest the presidency.

[13] See URAIA/IRI (2012: 15-18).

[14] This choice overlooked Raila Odinga and former minister Katana Ngala, and former vice presidents George Saitoti, Kalonzo Musyoka and Musalia Mudavadi.

[15] The Kibaki faction for instance rubbished a Memorandum of Understanding that provided for equal shares of the cabinet with the Odinga faction of the party.

[16] The 2007 presidential election circumstances are documented in the Kriegler Report, available at https://kenyastockholm.files.wordpress.com/2008/09/the_kriegler_report.pdf. The post-election violence is explored in the Waki Report, available at http://kenyalaw.org/Downloads/Reports/Commission_of_Inquiry_into_Post_Election_Violence.pdf. For an academic approach to the issues, see Kanyinga and Okello (2011).

[17] The Agendas were as follows: 1–Immediate action to stop the violence and restore fundamental rights and liberties; 2–Immediate measures to address the humanitarian crisis, and promote healing and reconciliation; 3–How to overcome the political crisis; and 4–Addressing long-term issues, including undertaking constitutional, legal and institutional reforms; land reform; tackling poverty and inequality as well as combating regional development imbalances; tackling unemployment, particularly among the youth; consolidating national cohesion and unity; and addressing transparency, accountability and impunity. For details, go to https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Background-Note.pdf

[18] An interesting analysis is available in Kenyan National Commission on Human Rights (2008).

[19] The manner of their creation was so ad hoc, leading to deeply contested boundaries and headquarters.

[20] Key individuals in his regime had campaigned against the Proposed Constitution, and only changed positions when it became evident the ‘Yes’ camp would carry the August 2010 national referendum.

[21] The Constitution ring-fences at least 15% of national revenue for county governments. In reality, however, the share has been nearly 40% of the revenue.

[22] See Ministry of Local Government (2012).

[23] Transition Authority (2016) is an elaborate end term report. Sun, August 20th 2017.At

[24] See Njeri Rugene and Patrick Langat, President Kenyatta defends tenure, seeks second term. Daily Nation, Tuesday March 21, 2017.

[25] Kenyatta I’s Kiambu people provided the ‘home guards’ who fought against the Mau Mau largely from the Kikuyu lands across the River Chania. The Kiambu position was therefore that the presidency (and its motorcade [snake]) should never cross into the other lands.

[26] See for example, Paragraph 545 in Kenya National Commission on Human Rights (2008).

[27] For example, see Nzau Musau, Why Decision 2013 was ridiculed, torn apart by scholars. Standard Digital, Sun, 20th August 2017. At https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/article/2001251923/why-decision-2013-was-ridiculed-torn-apart-by-scholars

[28] Aljazeera, Uhuru Kenyatta to court: “We shall reisit this”. 2nd September 2017. At http://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/09/uhuru-kenyatta-court-revisit-170902130212736.html