The Supreme Court’s courageous act of annulling Kenya’s August 8, 2017 presidential election seems to have plunged Kenya into a deep political crisis, especially after the withdrawal of Raila Odinga and Kalonzo Musyoka from the October 26 re-run. However, if the court’s decision compounded Kenya’s political crisis, it was not so much because it radically departed from Africa’s well-thumped jurisprudence on presidential election disputes. Rather, it was because the court inadvertently saddled Kenyans with an electoral coup — something that neither a resolute and courageous court nor a beleaguered and isolated opposition could contain, singly or jointly.

The Supreme Court judges and a renegade commissioner blew the cover off the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC). The strategically located co-conspirators within the IEBC were identified and named, but unashamedly stayed put. The IEBC threatened to revert to its factory settings.

Ominous indicators

The Supreme Court expected nothing but a fresh election held in strict accordance with the constitution and the law. However, barring a last-minute court intervention out of the many cases now before the judges of High Court and the Supreme Court, Kenya looked set for a coup.

Several ominous indicators pointed to the possibility of a coup: Externally, the contested presidential election re-run on 26 October was notably and explicitly endorsed by the United Nations, the African Election Observer Group, and the US-led “international community”, which downplayed fears expressed by the IEBC’s commissioner Roselyne Akombe and its chairman Wafula Chebukati that the IEBC, as currently constituted, could not hold a credible election. These officials told the world that the IEBC was compromised and was held captive by four commissioners, some members of staff and the Chief Executive Officer, who opposed the chairman’s proposed reforms.

Internally, signs that a coup was in the offing included the military-like poses of the Jubilee party’s leaders, who were seen wearing red berets and military fatigues (contrary to the law) in readiness to salute any order given by their commander. The subliminal message of this militant posturing was not lost on the Kenyan public.

In a show of military might, the government sent the paramilitary and police mostly to opposition strongholds of Western Kenya, Coast, Nairobi and parts of the Rift Valley. There were also reports of militia groups allied to the Jubilee party taking a new form of Nthenge oaths in Nairobi’s Lucky Summer estate to the chants of “thaiya thai thai”.

Internally, signs that a coup was in the offing included the military-like poses of the Jubilee party’s leaders, who were seen wearing red berets and military fatigues (contrary to the law) in readiness to salute any order given by their commander.

On its part, the opposition withdrew from the presidential election and vowed that there would be no election on 26 October. It violently disrupted IEBC preparations for the new election in the counties of Siaya, Homa Bay, Migori and Kisumu. It remained intransigent, bloodied but unbowed, mobilised and charged, but isolated internationally.

The counter-coup

The C-word (coup) has been used by some Kenyans to define the significance of the 1 September 2017 Supreme Court verdict nullifying the 8 August election. None other than Uhuru Kenyatta, the would-be principal beneficiary of the IEBC’s “illegalities and irregularities”, rattled and rankled by the court’s decision, called the court’s verdict a judicial coup. He was echoing the dissenting Supreme Court judge Njoki Ndungu’s verdict in which she cast aspersions on the integrity of the majority of her fellow Supreme Court judges and of the judicial process that led to the nullification of the election.

However, Uhuru’s charge of a judicial coup is a non-starter. It lacks the watermarks of one. There is no credible evidence that by annulling the presidential results the majority in the Supreme Court bench acted in haste, exercised their powers in an extra-constitutional or illegal manner, or declared an underserving candidate the winner of the 2017 presidential election – all backed by the threat or use of violence, against anyone and everyone resisting such a plot.

Uhuru’s charge of a judicial coup, therefore, served to divert attention from what truly imperils Kenya’s democracy: electoral coups.

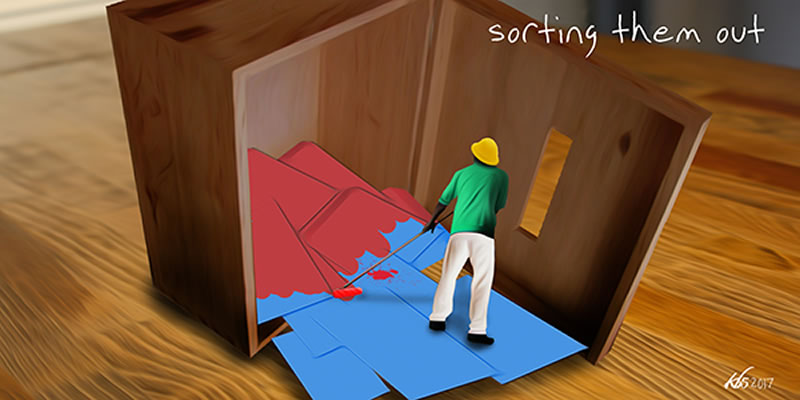

An electoral coup is a fairly recent phenomenon but has striking similarities to a military coup d’état. In both electoral and military coups, the conspirators identify the strategic locus or loci of state power, which they attempt to infiltrate and control. They then use these centres of power to acquire the remaining levers of state machinery, and eventually the state.

But before we get to that point, we must ask whether the concept of a coup hold the key to understanding the complexity of Kenya’s electoral politics at this juncture? Technically no, because in a classic coup d’état, the state is overthrown (usually through the use of violence) by a rebel or military group. In this case, it was the state that engineered a coup to subvert or overthrow state institutions, particularly the electoral commission. So if the Supreme Court ruling was a judicial coup, then the 26 October election could be described as an electoral coup, or a counter-coup that sought to defy or invalidate the Supreme Court decision.

An electoral coup is a fairly recent phenomenon but has striking similarities to a military coup d’état. In both electoral and military coups, the conspirators identify the strategic locus or loci of state power, which they attempt to infiltrate and control. They then use these centres of power to acquire the remaining levers of state machinery, and eventually the state. All coups succeed or fail to the extent that they are able to create and sustain a perception of victory once they have seized a strategic locus of state power.

The coup plotters deploy threat or use of violence against those who may resist them, and carefully identify their friends as well as their enemies and opponents whose capacity for resistance must be sabotaged or neutered sequentially or simultaneously. Some of these enemies must be targeted through a long-term process, but others must be taken by surprise on the day of the coup.

Electoral coups also adopt military warfare techniques, such as the use of psychological operation tactics (pys-ops) and the use of civic spaces of democracy, such as Kenya’s oligopolistic “mainstream” media, PR agencies and social media. These tactics are used to create and sustain a perception of the incumbent’s inevitable victory or invincibility, to fan and exploit citizens’ fear of political violence, to intimidate the opposition, to sustain a façade of the independence of the electoral commission, and to dominate the framing of the political contest and narratives of victory and loss. Electoral coups can be bloody or bloodless.

Kenya’s experience in its last three elections suggests that electoral coups are made up of these elements and more. The preferred locus of execution of these coups has been the electoral management body, the Supreme Court, or both. It usually harangues the opposition to go to court, not for justice, but as means of obtaining judicial imprimatur for its politically cathartic and legitimating value.

Military coups

Pictures of army tanks rolling down the city’s main street, soldiers in military fatigues with belts of bullets strapped across their chests patrolling the streets or standing guard around iconic public buildings within a capital city, the seizure and control of the state-owned national radio and television station by these forces, the continuous broadcasting of political martial music and “revolutionary” messages by “a redemption council” or “a revolutionary council” – these images are usually associated with military coup d’états, which generally set an organised army unit or units against the rest of the armed forces and society, which they dominate both by the threat or use of force, superior organisational ability, weaponry and the capacity to outlast any resistance.

In a paper published by the Albert Einstein Institution, Gene Sharp and Bruce Jenkins define a coup as “a rapid seizure of physical and political control of the state apparatuses by illegal action of a conspiratorial group backed by the threat or use of violence.” This speaks to the surprise, speed, means and the immediate strategic targets of coup makers.

However, there is more to the making of military or other types of coups. A military coup d’état is typically the ultimate pitched battle, asymmetrical warfare between the coup plotters who command an army or units of armed formations, on the one hand, and the armed formations of the state that are not party to the plot, on the other. The state could or could not be aided in its resistance to this power grab by civic institutions and unarmed but organised political groups, as well as rag-tag militia.

Competitive authoritarian regimes are states whose politics is defined by an odd mix of nascent liberal democracy and authoritarian carry-overs from one-party rule. These regimes are torn between democracy (with its strong local support base) and declining international support of its yesteryear benefactors (the West) who are playing catch-up with the rising authoritarian pull of a Chinese debt-bondage driven by a multipolar global system.

Coups are executed with speed, but take a long time to plan. They involve the identification, infiltration and control of strategic loci of state power. Usually, coup makers recruit key persons in charge of critical functions at strategic loci of state power, people whose simultaneous or separate but sequential acts, under the instruction of the coup plotters, enable the coup makers to take control of a strategic centre of state power, and use that to take control of the rest of the state machinery and to impose their rule on a people.

Coups in competitive authoritarian regimes

Competitive authoritarian regimes are states whose politics is defined by an odd mix of nascent liberal democracy and authoritarian carry-overs from one-party rule. These regimes are torn between democracy (with its strong local support base) and declining international support of its yesteryear benefactors (the West) who are playing catch-up with the rising authoritarian pull of a Chinese debt-bondage driven by a multipolar global system. Their politics is asymmetrical warfare, neither wholly determined by brute force (by the state security apparatus, state-sanctioned militia or opposition sanctioned militia) nor by civic actions, but by a mix of both, especially during general elections. Courts play an important role in recalibrating the balance of forces in this warfare.

Although military tanks on the streets of a capital city represent the dominant image of a coup d’état, there can be many other types of coups, defined by the locus of their execution, as there are centrally located levers of state power in a competitive authoritarian regime. The conspirators can seize these strategically-placed levers of state power and use them to control the rest of the state machinery.

In a competitive authoritarian regime such as Kenya, it is these loci of power – defined by highly centralised bureaucratic structures and decision making in the hands of a few – that are the prized targets of coup makers. The IEBC’s national tallying centre and the Supreme Court of Kenya fall into this category.

Elections are a perilous moment for such regimes. They present the ruling party with a dilemma: how to stage electoral contests that do not threaten the status quo but lend the regime a veneer of democratic legitimacy. Such democratic charades have great purchasing power among the self-declared “international community” (Western powers), especially in a world where political stability, as opposed to democratic niceties, is gaining currency.

Elections are anxious moments because they are a time when state power rests and shifts from one temporary locus to the other – from the substantive holder of the office of the presidency to the electoral commission or the judiciary. The electoral commission or the judiciary act as temporary custodians of state power, with enormous fiduciary powers. As the interim custodians of both state power and the people’s will, the chairman of the electoral commission or Supreme Court judges, acting singly or jointly, can declare any presidential candidate a winner according or contrary to the democratic will of the voters, the constitution and electoral laws.

Several acts, sequentially executed, in the run-up to and after the last three general elections in Kenya, seem to suggest that electoral coups have become the preferred mode of grabbing state power under the guise of a competitive election.

What’s more, an electoral moment throws up multiple strategic vulnerabilities: the counting, tallying and declaration of election results and the resolution of any dispute arising from such an exercise. Any of these loci of state power can be seized and used to acquire the rest of the state machinery. Or a combination of all these points can be captured and used to acquire the rest.

Kenya’s electoral coups

Several acts, sequentially executed, in the run-up to and after the last three general elections in Kenya, seem to suggest that electoral coups have become the preferred mode of grabbing state power under the guise of a competitive election. These coups are executed through a process of infiltration, seizure and control of the electoral management body to produce preferred outcomes and through the use of a cross-section of state security to put down any resistance.

Since 2007, Kenya has experienced this form of power grab, partly made possible by the electoral management body’s acts of “human error, fatigue, and technological failure” – which always happen only in favour of the incumbent or the incumbent’s preferred candidates – and by the cynical invocation or use of the judicial system to legitimise such a power grab.

The 2007 Kibaki coup

Mwai Kibaki’s 2007 power grab surprised many, not least the Kriegler Commission, which noted the strange circumstances surrounding the final announcement of the results of the presidential election and the low-key swearing-in ceremony at State House on the evening of 30 December 2007, a day before the official expiry of Kibaki’s first term in office.

Protracted political stalemate at the Kenyatta International Conference Centre (KICC), the national tallying centre, could have spilled over into a crisis of legitimacy for the incumbent, denying Kibaki the strategic advantage of bargaining with his opponent from an advantaged position as the commander-in-chief of the all the armed forces who could exercise the full powers of the office of the president.

Kibaki’s 2007 “victory” out of a muddled electoral process was a coup; it relied on sequential or simultaneous acts of infiltration and control of a strategic locus of state power (the ECK) and used the threat of violence to neutralise resistance.

Many Kenyans were surprised by the sight of the “Ninja turtles” that descended on the KICC just before the results were announced. These police officers – dubbed “Ninja turtles” by Kenyans because of their striking resemblance to the fictional Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle cartoon characters – are mostly from the Rapid Deployment Unit of the Administration Police, the police unit that is under the command of the Minister of Internal Security and which had grown spectacularly in strength, capability and numbers during the Kibaki regime.

The political significance of the chaos at KICC – with the chairman of the electoral commission, Samuel Kivuitu, literally under siege – the hasty swearing-in of Kibaki at dusk and the growth in numbers and strength of a civilian-commanded police force under a regime that ostensibly upheld citizens’ right to protest and picket was not lost on the majority of Kenyans.

Similarly, the political significance of the lack of preparedness of all the armed forces, except the military, and the lack of co-ordination among security chiefs at various levels (district, provincial and national) was not lost on the Waki Commission that was set up to look into the violence that erupted after that disputed election.

These acts, coupled with the cordoning off of the KICC by the General Service Unit (GSU), the revelation that the Electoral Commission of Kenya (ECK) had been infiltrated by the National Intelligence Service and rogue returning officers, and the opaque system of counting and tallying results at the KICC, suggested a coup plot via the electoral locus.

Kibaki’s 2007 “victory” out of a muddled electoral process was a coup; it relied on sequential or simultaneous acts of infiltration and control of a strategic locus of state power (the ECK) and used the threat of violence to neutralise resistance. It deployed police around the main entrances and exits of urban slums, cordoned off public spaces, such as Uhuru Park, for months on end and restricted public broadcasts to weaken the opposition’s ability to organise or mobilise protests against the regime.

The successful execution of a coup requires the active participation of some armed formations that have the capability to repress any anticipated forms of armed or civilian resistance. It also requires “neutral” or “professional” police and military forces – an unprepared police force, security committees that didn’t meet, and a prepared but professional army, which maintains its neutrality while the coup plot unfolds. Such a coup can gain legitimacy through the tacit or explicit approval of the international community, particularly countries whose military bases are located in Kenya, the UN headquarters in Nairobi, and strategic countries that Kenya relies on for military support.

Simply put, a Kibaki-style coup plot succeeds when it faces no credible or active internal threat from any other armed formation, except the unarmed civilian mobs of protestors or gangs armed with bows and arrows, who can easily be contained by the police and the paramilitary under the guise of maintaining law and order.

Kenya’s first successful electoral coup in 2007 was bloody. But if the securocrats and the Kibaki-aligned political elite hewed Kenya’s body politic “like a carcass fit for the hounds,” in 2007, then in 2013 they “carved it as a dish fit for the gods” with peace campaigns and “accept and move on,” messages.

How the Kibaki coup was executed and the resistance against it has informed the subsequent attempts. Though successful, Kibaki’s 2007 seizure of state power was seen to have had several weaknesses, which cost him the complete control of state power (a “nusu mkate” coalition government) and endangered real or perceived Kibaki supporters in opposition strongholds, especially in the Rift Valley. The resistance against it, nationally and internationally, nearly consumed the regime’s success.

Importantly, Kibaki’s plot had failed to create a perception of victory. His Party of National Unity’s campaign was seen as lethargic and as lacking an effective communication strategy: it failed to manage public perception (opinion polls) and to trumpet Kibaki’s economic achievements. Even its successful attempts to rope in top editors who authored “Save Our Country’ headlines was seen as a little too late.

Kenya’s 2013 electoral experience was sublime. The electoral process was a well-designed psychological operation to create and sustain a perception of victory, coupled with mediated reportage and embedded intellectuals, as well as co-option of a cross-section of the civil society groups to preach peace.

Similarly, its diplomacy was wanting and no match for the diplomatic charm offensive of some of Kenya’s astute human rights and democracy activists who had contacts in high places in the West. It strengthened the opposition, the pro-democracy forces and the reform agenda against the regime. Importantly, it allowed too many concessions, especially the enactment of the 2010 Constitution of Kenya.

The 2013 digital coup

The evil genius of the Jubilee party’s 2013 electoral coup was to turn Kibaki’s coup on its head: rewrite the old military coup d’état manual and distill out of it evil lessons with which to subvert Kenya’s democratic processes and institutions.

Kenya’s 2013 electoral experience was sublime. The electoral process was a well-designed psychological operation to create and sustain a perception of victory, coupled with mediated reportage and embedded intellectuals, as well as co-option of a cross-section of the civil society groups to preach peace.

Critical media coverage was disarmed through peace journalism. Media coverage critical of the IEBC was equated with inciting political violence. Claims by the opposition, which deserved a critical look, were brushed aside as acts of incitement. Jubilee ran a glitzy and energetic campaign. Its victory was prophesised by the talk of a “tyranny of numbers” that assured a win for the UhuRuto alliance.

In 2013, the locus of the electoral machinery was relocated to the Bomas of Kenya (a rondavel-like auditorium that was created to host cultural events), away from Nairobi central business district and an easy location to secure. The election was choreographed as a national cultural event or a public holiday that culminates in the appearance and address by the president. Choirs sang to soothe the anxieties of a nation still smarting from the trauma of the 2007 general election, anxiously awaiting the announcement of the winner, while the electoral body’s commissioners, like members of a cultural troupe, took turns to announce the results.

Yet something was amiss. The biometric voter identification and electronic transmission of results failed. The numbers being beamed on the screen were not adding up; they were not even divisible by a factor that Isaak Hassan, the then chairman of the commission, said was the multiplier. Rejected votes seemed to have been the unnamed candidate in the race. There was no way to verify that the numbers presented by the IEBC truly reflected the will of Kenyan voters.

The result was strategically announced in the middle of the night to give security forces ample time to plan for any form of resistance. As many as 150,000 officers from different armed formations (Kenya Police, GSU, Prisons, Kenya Wildlife) had been mobilised, trained and deployed to secure the 2013 election, though this was not made public.

The coup de grace was delivered through a pys-op that at once painted Raila Odinga as the personification of political violence and harangued him to accept the results of the presidential election, and if he was dissatisfied, to seek judicial redress.

Aggrieved by the results, the Raila-led opposition went to court. The newness of the Supreme Court, the refreshing leadership of Chief Justice Willy Mutunga, a well-known human rights defender, and the court’s new olive green and yellow striped robes and no-wigs-or-bibs attire inspired confidence. However, the judges unanimously disallowed the bulk of the evidence the opposition had hoped would prove its case, citing constitutional time constraints.

The IEBC numbers on the 2013 presidential election, like its voter register, kept changing, and took an extraordinarily long time to finally be posted for public scrutiny. Without a stable register of voters, the “tyranny of numbers” became a self-fulfilling prophecy that no one could test, but a valuable tool for creating and sustaining a perception of invincibility.

The Supreme Court’s own self-initiated process of examining the records of the IEBC failed the integrity test. The court let the IEBC off the hook.

Kenyans had to wait for the 2017 new-look Supreme Court bench to get a glimpse into how the bureaucratic mischief, malfeasance and malice by the IEBC secretariat works to produce winners of presidential elections, and to get a sense of what goes on within secured spaces, away from the public glare, where IEBC clerks verify and tally the results of various polling stations.

The IEBC numbers on the 2013 presidential election, like its voter register, kept changing, and took an extraordinarily long time to finally be posted for public scrutiny. Without a stable register of voters, the “tyranny of numbers” became a self-fulfilling prophecy that no one could test, but a valuable tool for creating and sustaining a perception of invincibility.

August 2017: Robbery with violence

This year’s script was an amalgam of the 2013 and the 2007 experiences. Several reform processes and anxieties around insecurity during elections provided a perfect cover. The locus of the execution of the coup was the IEBC, buoyed by the mantra that no court in Africa has ever nullified a presidential election.

The 8 August 2017 election was preceded by a number of preemptive strategies and strikes, variously aimed at pro-democracy non-governmental organisations and foundations associated with key opposition figures with the aim of incapacitating resistance against the regime. The NGO Coordination Board’s attempts to close down the accounts of the Kalonzo Musyoka Foundation, the Kidero Foundation, and a foundation associated with Rosemary Odinga, Raila’s daughter, fall into this category. Libel laws enacted by the Jubilee government and the creation of a central government advertisement agency also came in handy when manipulating Kenya’s oligopolistic main-street media.

Resistance to an electoral coup was largely expected to rise from the core of Raila Odinga’s constituency and a few human rights and democracy non-governmental organisations. Jubilee went for both with speed once the result had been declared: indiscriminate state violence and attempts to close AFRICOG and the Kenya Human Rights Commission fall into this pattern.

How Jubilee executed this year’s scheme is a classic study on how a coup strategy was interwoven into Kenya’s electoral process and performed through routine acts of government functions, using the very institutions democracy depends on, without rousing suspicion among the citizens. A look at its key aspects demonstrates how an electoral coup works.

The Jubilee campaign, like the one in 2013, was energetic and glitzy. It was largely amplified by the President’s Delivery Unit’s advertisements: “GoK Delivers”; “+254 Tuko na Plus Kibao”; advertisements that claimed that Kenya had registered exceptional achievements in many fields, such as provision of “free” maternity services amidst a protracted strike by health workers. Jubilee made several campaign forays into what were considered swing constituencies or loose pro-opposition strongholds in Kisii, Bugoma, Kajiado and other areas.

If issues do not count in Kenya’s politics, and only ethnicity does, then how could the government improve its electoral chances when the Jubilee government is widely perceived to be dominated mostly by the elite of just two ethnic groups and didn’t even attract any significant symbolic defection of notable ethnic leaders in the run-up to the August 8 election?

Regime-aligned intellectuals, like Misigo Amatsimbi, writing two days before the poll, predicted Jubilee’s victory, complete with the numbers and the expected ethnic shifts in voting patterns. These numbers, expressed in percentage form, bear an uncanny resemblance to the figures IEBC would later disown in court, and variously call “data, provisional text data or statistics”.

Narratives of Jubilee’s victory, mostly by analysts who had simply ignored the confounding figures IEBC was beaming through the public portal, used “data” from secondary sources, used only form 34B, or relied on the incomplete records of the polling station results, the form 34A.

Vowing that Kenya’s presidential election was nothing but an ethnic census, where issues count for little, Misigo used the last census figures to approximate the number of votes that either Raila Odinga or Uhuru Kenyatta would get at varied levels of voter turnout among various Kenyan ethnic groups. In this analysis, Jubilee recorded a remarkable improved performance among the following ethnic groups: Somali, Samburu, Borana, Luhya, Maasai, Kamba and Kisii. Amatsimbi predicted 10.6 million votes (54%) in Uhuru’s first round win against Raila Odinga’s 8.8 million votes (44%). Misigo’s narrative and numbers don’t just add up.

Charles Hornsby had a similar prediction, which was based on a more sophisticated model that was gleefully rehashed by Bitange Ndemo, another regime intellectual, but which curiously sought validation in the hard-to-vouch form 34B after the declaration of the results.

Nor does “the Jubilee inroads into the opposition stronghold” narrative hold water. If issues do not count in Kenya’s politics, and only ethnicity does, then how could the government improve its electoral chances when the Jubilee government is widely perceived to be dominated mostly by the elite of just two ethnic groups and didn’t even attract any significant symbolic defection of notable ethnic leaders in the run-up to the August 8 election?

Infiltration and control of the commission

These numbers served an important role. They conditioned Kenyans to accept a Jubilee victory as something that had been scientifically foretold. They also enabled the narratives of certain victory, which gained currency immediately after the IEBC announced the results.

However, it is now clear that no one, not even the IEBC, could vouch for them. What is more, it is now clear how bureaucratic mischief, malice and malfeasance account for what was previously excused as “human error, fatigue and technological failure,” and how these acts produce presidential victory.

Wafula Chubukati, the chairman of the electoral commission, declared Uhuru Kenyatta the winner of the presidential election without receiving results from a substantial number of polling stations. Why did Chebukati declare the results of the election prematurely when the law allowed a few more days for a thorough job? Why was he waffling, lost in procedure, before declaring the results of the August 8 presidential election?

The Supreme Court found that numerous election return papers, notably form 34 C for the declaration of presidential results, lacked the mandatory security features, which raised suspicions that they could be fake. Why did Ezra Chiloba, the CEO of the IEBC, repeatedly remind Kenyans that the results being beamed through the public portal were results from 288 out of 290 constituencies shortly before the results were declared, only for the IEBC to disown these results as “data, provisional text data, statistics”?

Chiloba also told the BBC that some data entry clerk created an email account in the chairman’s name without the chairman’s knowledge, and used it to conduct about 9,000 transactions in the electoral database. Chiloba’s only regret was that the account was not created under a different (institutional) name. He did not question the ethical issue it raised: Why were these transactions conducted without the knowledge of the chairman? What motive was behind this?

According to the IEBC, in the 8 August election, there were more than 11,000 polling stations that were out of reach of the network coverage of Kenya’s three mobile service providers. However, in the fresh election on 26 October, this number had reduced drastically to only 300. This reduced figure was not accompanied by any report that showed that the mobile phone companies had made massive investments to improve network coverage between the August election date and the election date in October.

IEBC’s conduct reeks of bureaucratic mischief, malice and malfeasance. Chebukati and Akombe’s memos indicating that not everything was above board point to this. There can be no doubt that the IEBC is a compromised institution, infiltrated and controlled by those who control four of the now six commissioners. The devil is in the malicious detail of everyday bureaucratic decisions, procedures, rules and regulations. In the Maina Kiai versus the IEBC case, the Court of Appeal warned the IEBC against this kind of mischief. However, the IEBC’s defiance of court orders points to a compromised institution that enjoys the protection of the powers that be.

Hotspots talk

In the run-up to the August 8 election, claiming to have learnt from history, the Kenya Police, the National Cohesion and Integration Commission and the IEBC mapped, profiled and marked regions that they referred as hotspots. The state mobilised an unprecedented 180,000 officers from various armed formations, over 30 specialised armoured anti-protest vehicles and helicopters for rapid deployment. (Coup plots work best with a mixed force, capable of executing orders as given, but incapable of executing a countercoup.)

At first glance, the list of places labeled hotspots appeared inclusive, it contained both the incumbent’s and the opposition’s strongholds, areas that had experienced political violence in the past general elections. However, some state action told a different story. The police held protest control simulation only in Kisumu and Nairobi. Only Kisumu and Oyugis, both in the opposition stronghold, received body bags, ostensibly as part of first aid kits donated by an NGO. That’s a Kenyan first in the history of first aid.

The lopsided deployment of the armoured vehicles, body bags and rehearsals for protest control told a different story. It suggested a strategy informed by a predetermined electoral outcome, a contest with a known winner and loser, and predictably, where the results of the presidential election would either bring joy or disappointment.

The Supreme Court stood up to something insidious that has been gnawing at the heart of Kenya’s democracy since 2007, something that neither the Johann Kreigler Commission in 2007 nor the Supreme Court in 2013 managed to correct. Unlike Kibaki’s 2007 coup, which unintentionally produced comprehensive reforms, the 2017 plot seeks to upend the 2010 Constitution of Kenya.

Hotspots talk was a camouflage. It provided a perfect cover for an armed repression of protests against the IEBC’s attempt to unconstitutionally and illegally make Uhuru Kenyatta the president of Kenya. Recent human rights reports now confirm that the police may have killed up to 67 people, mostly in opposition strongholds, and especially in urban slums.

Monopolising the narrative

If the violence of an electoral coup looks strikingly similar to that of a classic military coup, then how it monopolises communication in a pluralistic media landscape sets it apart from the latter. In a typical military coup in a state-owned media era, the seizure and control of the only broadcast house more or less guarantees the coup makers a monopoly over the most effective means of communication.

Kenya’s experience suggests that the electoral coup plotters used a markedly different approach to attain the same results. The idea was not so much to seize a broadcast house as it was to dominate the narrative on the critical aspects of the electoral process. This was achieved through various approaches, including intimidation of media houses, ordering broadcasting stations to not announce unofficial presidential results, imposing a reliance on the IEBC “public portal” (the pot of statistics and provisional text data, which the commission itself disowned), and investment in heavily PR-mediated news reporting and analysis.

PR spins

The PR spin on the results was remarkable. As Wandia Njoya pointed out, in reporting the results, the burden of proof was put on the opposition to “substantiate the claims”, not on the IEBC, the principal author of the confounding statistics, to explain the anomalies and irregularities, the processes, and the missing polling station data (forms 34A). Any coverage that deflected attention away from the IEBC was welcome. Favourable observer reports were amplified, while those critical of the process were suppressed.

The Cabinet Secretary in charge of communication and the government’s communication authority repeatedly warned Kenya’s “main-street” media against broadcasting unofficial results and threatened sanctions on any media house that would dare to broadcast them. These directives of questionable legal basis had one effect: they allowed the government to control the narratives on the election. Moreover, the government raided the opposition parallel vote-tallying center in Nairobi. This was an attempt to neutralise any competing source of information and make the citizenry dependent on the only one source of information, the one controlled by the compromised electoral commission.

Rollback of reforms

Whether or not the Supreme Court upheld or annulled the results of the August 8 presidential election, Kenya’s democracy was damned either way. The judicial coup would inevitably be followed by an electoral counter-coup.

The Supreme Court stood up to something insidious that has been gnawing at the heart of Kenya’s democracy since 2007, something that neither the Johann Kreigler Commission in 2007 nor the Supreme Court in 2013 managed to correct. Unlike Kibaki’s 2007 coup, which unintentionally produced comprehensive reforms, the 2017 plot seeks to upend the 2010 Constitution of Kenya.

The Court exposed the Jubilee government’s attempt to rewrite the Kibaki plot, whose ambition included the control of all centres of power that check the presidency. Momentarily, the court had wrong-footed a well laid-out coup plot whose full scope will, hopefully, become clearer once the unprecedented 300 election petitions filed against various candidates in the just concluded general election, especially those from the “inroad” constituencies, are determined.

A weird reversal of aspirations seems afoot. The government has created an incumbent-friendly electoral commission. It only awaits presidential ascent or tweaking to take care of any contingency, for example, the resignation of its chairman. If this becomes law, it will institutionalise all the IEBC’s bureaucratic mischief, malfeasance and malice that led to the annulment of the August 8 presidential election.

By Akoko Akech

Akoko Akech, presently a graduate student at the Makerere Institute of Social Research, was the program officer in charge of the Society for International Development (SID-East Africa) and Institute for Development Studies’ book project, Karuti Kanyinga and Duncan Okello (eds.,) Tensions and Reversals in Democratic Transition: Kenya’s 2007 General Election, and the Working Paper Series on the Constitution of Kenya, 2010.