This was due to be the last in a series of four articles on the Kenyan general elections of 2017. The first three looked at the campaign, the state of play between the main alliances and the capabilities and activities of the Independent Elections and Boundaries Commission and made a series of predictions about the likely results of the 8 August poll at presidential, gubernatorial and parliamentary levels. This article looks at what happened next: the results, where those predictions were right and wrong, what we can deduce about the conduct of the electoral process in the light of the Supreme Court’s invalidation of the presidential poll on 1 September and what lessons there may be in the first presidential poll for the second.

The Presidential Results

In the Presidency, as predicted in all three articles, according to the Form 34Bs which record the 290 constituency results, Uhuru Kenyatta won a clear victory; winning 54% of the vote to 45% for his main challenger Raila Odinga. This was the result of an electoral process which initially pleased almost everyone. The procedures on polling day worked well, the electronic voter identification and tallying systems mostly functioned as intended (or at least as predicted), there was no military intervention, no mass failure of the electronic voter verification system and counting at the polling stations was mostly uneventful. The presidential results were (mostly) logical and consistent with previous elections and with the parallel elections taking place and there were no excesses of votes in the Presidency compared to the other polls. The overall process was given the support both of domestic and international observers (with qualifications as the results had not yet been declared at that point).

For now, this analysis is based on the opinion – which I hope to explain – that while there were material administrative issues sufficient in the minds of the Supreme Court to invalidate the election, the evidence strongly suggests that the presidential results announced by IEBC were not “cooked” or “computer generated”.

That is not the view of a large number of Kenyans who supported the NASA coalition however, nor of the Supreme Court, and we will look in more detail at their concerns later. For now, this analysis is based on the opinion – which I hope to explain – that while there were material administrative issues sufficient in the minds of the Supreme Court to invalidate the election, the evidence strongly suggests that the presidential results announced by IEBC were not “cooked” or “computer generated”. Many of the complaints raised relate to the IEBC’s partial migration to an electronic tallying system, which as predicted was a key source of confusion.

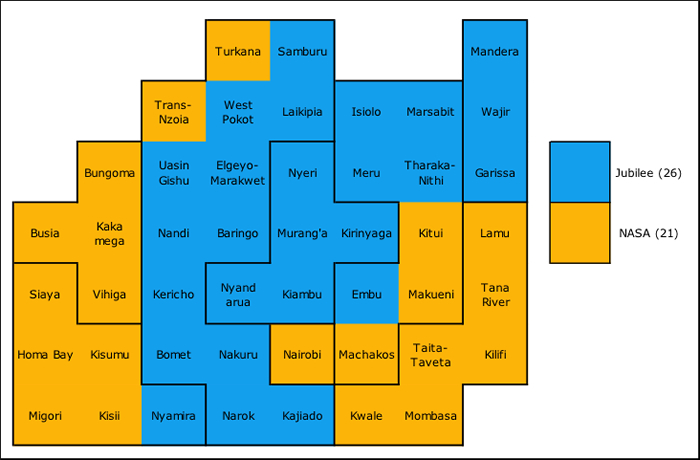

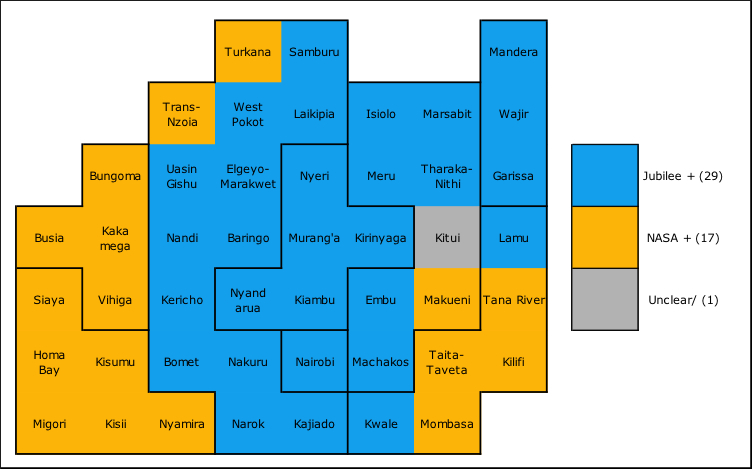

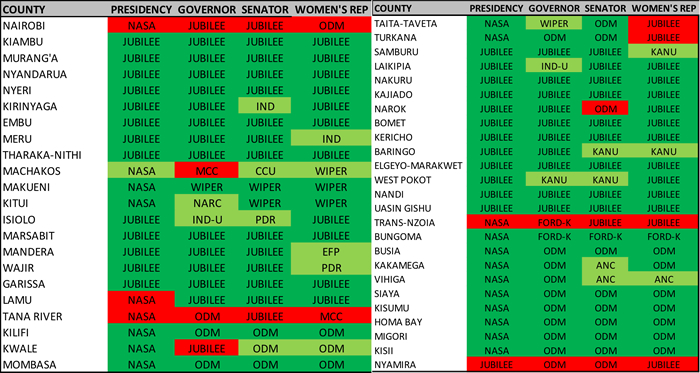

Overall, the IEBC results showed that Kenyatta and William Ruto had won a decisive victory, by a greater margin than most had predicted. They won 26 counties to Odinga’s 21. Uhuru won three counties I thought he would lose – Garissa, Narok and Nyamira – and lost one, Tana River.

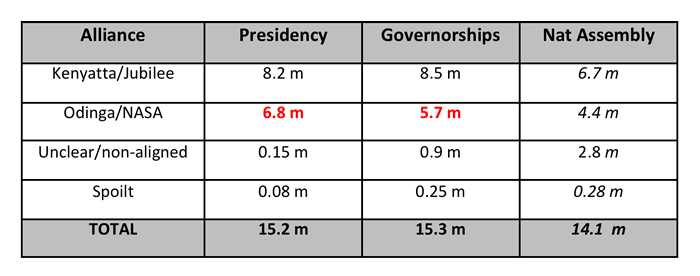

I got closest in my article in June, which predicted a 55-45% victory, In fact, the closer to the election we got and the more information I acquired, the less accurate my predictions were. In fact, I had begun to doubt my own numbers and modified my eve-of-poll prediction from 53-47% (which the spreadsheet suggested) to 52% to 48%. I left however the predicted votes for each candidate the same, and there I was pretty close: the official constituency Form 34Bs show that Kenyatta beat Odinga by 8.2 million to 6.8 million votes, compared to which I had predicted 8 million to 7 million.

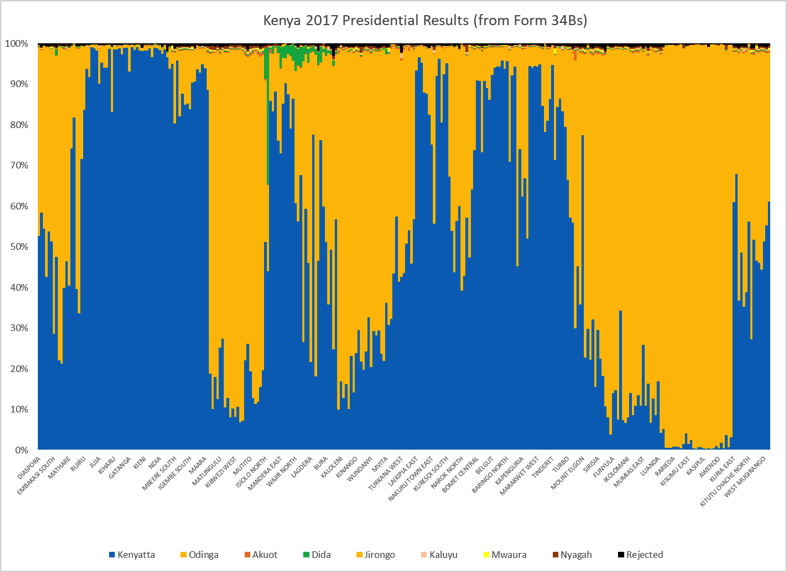

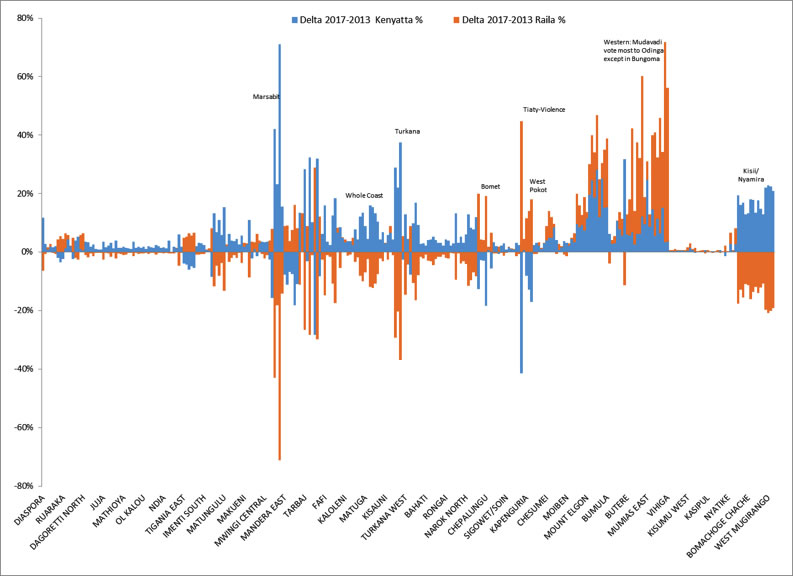

Regionally, Kenyatta and Odinga (and their respective Vice Presidential candidates William Ruto and Kalonzo Musyoka) won all their Kikuyu, Kalenjin, Luo and Kamba “heartlands” as expected, and by huge margins. The two internal “insurgencies” in Bomet (Isaac Ruto for NASA) and Machakos (Alfred Mutua for Jubilee) both had little impact on the presidential votes. I had expected Ruto to bring more voters to Odinga than he in fact did. Little will change here in a rerun. As predicted, Kenyatta won most of the north and North east, Odinga most of the Coast and Western. Nairobi (on the far left of the chart below) was narrowly pro-Odinga (51% to 48%), much closer that opinion polls had predicted, a source of some surprise. Ipsos for example had run a survey in Nairobi just pre-poll which predicted a 56% Odinga vote with a margin of error of +-2.7%. The Kisii and Nyamira result (on the far right) were also a surprise, as most commentators, myself included, had given the region to NASA as in 2013. Explanations given afterwards included the heavy investment Jubilee had made in the region, the defection of virtually all ODM MPs to Jubilee and the influence of Fred Matiang’i as cabinet secretary.

Note: Orange throughout is NASA or Odinga; Blue throughout is Jubilee or Kenyatta. I use blue rather than red, the “Jubilee colour”, because red and orange look similar in some display formats, and because blue is a more “conservative” colour in most political systems than red, which tends to be associated with socialism and communism, and Jubilee is definitely a more conservative alliance.

As expected, all the other candidates were irrelevant, except for Joseph Nyagah (small spread votes) and Mohammed Dida (in green above), who polled creditably in the north and north east. Rejected and otherwise inadmissible votes were reasonable, down on 2013 at 0.5% overall (based on the Form 34Bs).

When I summed them manually, the 34Bs added up to almost exactly the same results as IEBC had announced around 8pm on 11 August (which they had done with a couple of seats still missing, as they were entitled to do).

These Presidential results are taken directly myself from the 34Bs, when they were published in a repository by IEBC, which were the only formal and legal basis for announcing a result. When I summed them manually, the 34Bs added up to almost exactly the same results as IEBC had announced around 8pm on 11 August (which they had done with a couple of seats still missing, as they were entitled to do). There were three Form 34Bs missing from the Forms repository (a different result had been uploaded instead), so I used the 34C national summary for them. The results in the IEBC real time portal (initially fed by the KIEMS system and then corrected and topped up later manually with missing results) were similar, though not identical, with the main difference being the spoilt votes, where – as in 2013 – there appeared to be an glitch which led the number of rejected, disputed and objected votes to be far larger electronically than in fact it turned out to be (something the IEBC has never explained).

Comparing the now invalidated presidential results against those for 2013 (easy with the same constituencies and candidates) we can see clear trends. Kenyatta did better in most areas, picking up votes especially in the north and North East, the Coast, Western and Kisii/Nyamira. Odinga did better in Bomet, some northern Kalenjin seats, most of Western (where he took the majority of Mudavadi’s 2013 vote) and Meru.

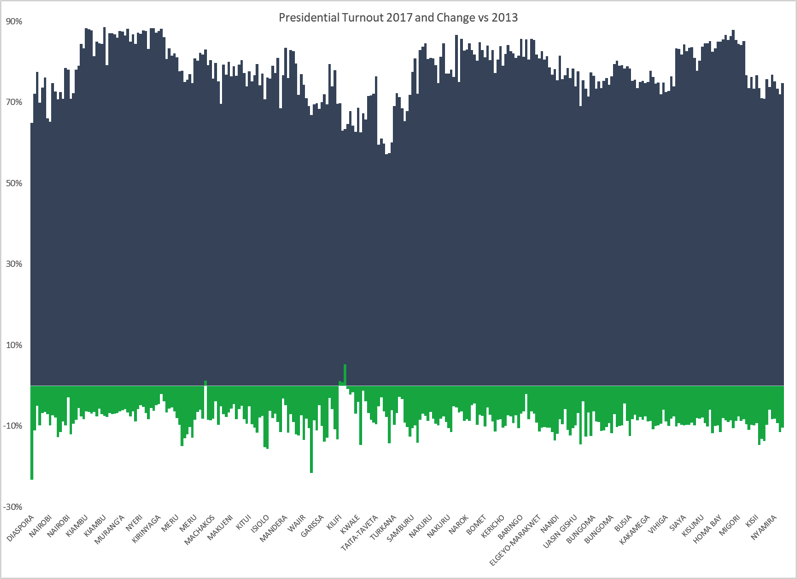

Turnout was substantially down on 2013. This was as predicted: the 2013 election had been fought on a new register, which had been only incrementally and partially updated since then, leaving at least a million dead voters still registered, so turnouts were inevitably going to be lower. In addition, the electronic voter identification system, with id cards, photographs and fingerprints combined, and (uneditable) tallies of voters maintained electronically by the KIEMS systems, deterred or prevented some “top up voting“ (officials voting for missing voters at the end of the day) which occurred in 2013.

In summary, if the Presidential result was substantively rigged or the result otherwise affected by the issues found, it is near certain that all the other elections must have been rigged or affected in the same way, as they involved the same voters, method for voting, technology for voter identification and results transmission (KIEMS), the same real-time results display portal, the same voting and counting processes, the same election officials and almost the same end results.

The turnout pattern (in black below) matched very closely that of previous polls, highest in the Luo and Kikuyu homelands, lowest on the coast. Turnouts exceeded 85% in 35 mostly Kikuyu, Luo and Kalenjin constituencies, a sign of some forced voting, top ups or stuffing, but exceeded 90% nowhere, and nationwide were a very reasonable 78% (compared to the 76% that a long-term weighted average of the last five elections suggested). The change in turnout on 2013 (in green below) was mostly consistent, as would be expected if dead voters were the main reason. Turnouts rose slightly in a couple of Kilifi seats where they had been depressed by the Mombasa Republican Council violence in 2013, and in Tharaka in Tharaka-Nithi (unexplained so far).

The Governorships

In the 47 gubernatorial races, the results followed a similar pattern to those for the Presidency. Again, Jubilee won decisively, by a greater margin than predicted. Here too, I underestimated the scale of Jubilee’s victory (though I got the winner right in 40 of 47). I predicted that Jubilee and their KANU, MCC, FAP, PNU, DP, NARC-Kenya and independent allies would win 21-28 Governorships, but they ended up with 29. As expected, they won their homelands, and Mike Sonko won Nairobi. Jubilee also won four counties where I had them as marginals (Narok, Kwale, Lamu and Wajir) and four (Garissa, Kajiado, Bomet and Machakos) which I had given to NASA. Across the nation, only 21 of the 47 incumbent governors returned to office.

New Governors included three Kenyatta first-term cabinet secretaries, all dropped from their posts for various alleged misdeeds: Anne Waiguru in Kirinyaga, Joseph ole Lenku in Kajiado and Charity Ngilu in Kitui – plus retired Kibaki-era Secretary to the Cabinet Francis Kimemia. This reaffirmed the illusory nature of the distinction between senior non-partisan state officials and politicians. If they were not in active politics when they entered office, they certainly were by the time they left.

For many Kenyans, the local races for MP and MCA were just as important as those for the President and Governor. There too, the same pattern was seen – Jubilee successes across the board.

NASA did not petition the governorship elections collectively, though they made allegations that some results were “computer generated” and initially, nor did most losing gubernatorial candidates. There seemed a general assumption that the non-presidential polls were not systematically rigged until the Supreme Court’s judgement, which immediately opened the floodgates for petitions by defeated candidates, including losing gubernatorial candidates, in Embu, Siaya, Kirinyaga and Machakos, with more to come.

The Parliamentary Races

For many Kenyans, the local races for MP and MCA were just as important as those for the President and Governor. There too, the same pattern was seen – Jubilee successes across the board. In the National Assembly, for the 290 constituency MPs my prediction of a 54% pro-Jubilee to 46% pro-NASA win turned out again to be a slight underestimate of the size of Jubilee’s victory. In fact, Jubilee and allies won roughly 60% to just under 40% for NASA. Jubilee did well in Bungoma and Kakamega (where ex-New FORD Kenya members formed the core of their victors), Kisii and Maasailand, and even won a couple of seats in Kitui and Machakos. ODM swept Luo areas and most of the Coast and Wiper most of Ukambani, while Mudavadi’s ANC, FORD-Kenya and ODM competed for the non-Jubilee western seats. Nairobi split 9 seats to Jubilee to 8 to NASA. The majority of MPs were newcomers, with voters clearly demanding change at the local level, particularly in the Kikuyu and Luo homelands, where few incumbents were re-elected.

The pattern was similar amongst the elected county Women’s MPs (with 31 for Jubilee and its allies versus 16 NASA and one independent) and in the Senate, where Jubilee and allies won 27 elected seats to NASAs 20). Overall, Jubilee won (initially) the presidency, the National Assembly, the Senate and most of the Governorships, the most decisive victory since the NARC wave of 2002.

Contrasting Perspectives and NASA’s Concerns

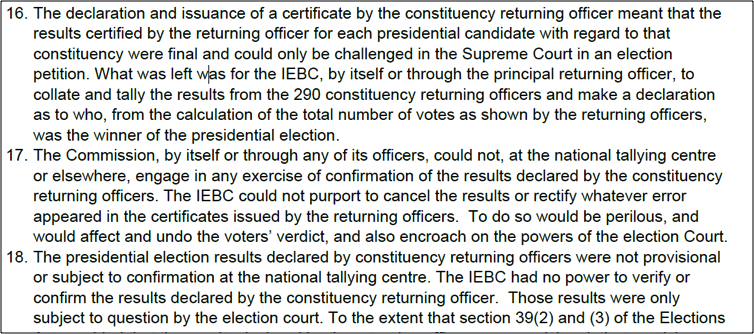

In general, the elections appeared to have been smoothly run, the results consistent, the electronic portal reporting convincing and the IEBC appeared comfortable in delivering its mandate. Observers commended the process as “peaceful, fair, and transparent”. Believing it had lost its ability to validate and correct constituency errors after the Maina Kiai et al case, IEBC headquarters limited itself – for the presidential election victory announcement – to a process of extraction, verification and entry of the 290 constituency Form 34B returns, the summing of these results and the announcement of the winner. As there remains dispute on this, the key decision summary is reproduced here from the Kiai judgement (http://kenyalaw.org/caselaw/cases/view/133874/):

The results Chebukati announced from the 34Bs (acknowledged by all to be without a complete set of 40,000 matching polling station Form 34As) matched closely with the parallel returns coming from the polling stations via the electronic KIEMS system in real-time to Bomas. From close of poll on the 8th, the parallel result stream from KIEMS soon showed a lead for Kenyatta and that lead grew over the next 48 hours as more and more of the electronic kits reported in.

The independent Parallel Vote Tabulation conducted by the ELOG domestic observer network and announced on 12 August validated the results almost precisely (its sample-based prediction gave 54% for Kenyatta to 45% to Odinga with a 1.9% margin of error). This was crucial because it provided independent verification to observers and the media that their perception of a well-run election was matched by independent assessment. Of course, this could have been faked, but there is no evidence yet offered that it was.

A macro-level comparison of voters cast and results between elections in fact shows that Odinga did better presidentially than his candidates in general. A re-tallying of the 15.3 million gubernatorial votes by constituency gives 5.7 million votes to ODM, Wiper, CCM, ANC, FORD–Kenya and allied candidates, far less than Odinga’s 6.8 million (in red). Thus Odinga did better in the cancelled presidential elections than did his gubernatorial candidates. The same pattern is seen in Parliament – again, Jubilee candidates polled more than 2 million more than NASA, though results are incomplete become 18 seats still don’t have full results on the Portal (https://public.rts.iebc.or.ke).

Jubilee = Jubilee + KANU + FAP + MCC + EFP + DP + PNU + NARC-Kenya plus defectors from the above after losing primaries, where known

NASA = ODM + Wiper + CCM +ANC + FORD-K + CCU + NARC plus defectors from the above after losing primaries, where known

Jubilee’s victories in the annulled presidency matched well with its victories in parliament and the Governorships. Comparing the Presidential, Gubernatorial, Senate and Women’s Representative results against each other by winner, in only nine counties did voters switch tickets: Nairobi, Machakos, Lamu, Tana River, Kwale, Taita-Taveta, Turkana, Narok, Trans-Nzoia and Nyamira.

Of those, Odinga won every one except Nyamira. In summary, if the Presidential result was substantively rigged or the result otherwise affected by the issues found, it is near certain that all the other elections must have been rigged or affected in the same way, as they involved the same voters, method for voting, technology for voter identification and results transmission (KIEMS), the same real-time results display portal, the same voting and counting processes, the same election officials and almost the same end results.

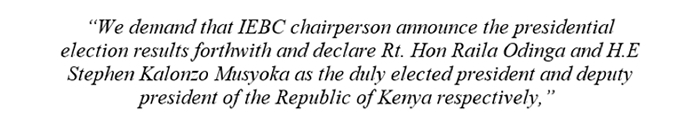

Rather than conceding once the trend was clear, Odinga rejected the presidential results outright (though not the other results) and accused the IEBC of a “complete fraud”. NASA’s impassioned follow up allegations were more specific, claiming form substitution, un-gazetted polling stations and administrative chaos in the IEBC and castigating the IEBC for releasing the presidential results without all the Form 34As. The sometimes-contradictory and implausible hacking claims made by senior politicians including Odinga, James Orengo and Mudavadi on 9-10 August raised the political temperature sharply, as intended, but also distracted attention for a while from real issues which were emerging relating to the IEBCs handing of the Form 34As. Despite widespread scepticism and challenge from the international observers, who had all judged the polls so far (before results had been announced) to be free and fair, NASA’s leaders refused to accept the results, claiming they were “cooked” or “faked” and demanded – even before all form 34B were in – that IEBC declare Raila as President (at one point using a faked NASA parallel count document as supporting evidence).

Unexpectedly abandoned by the international observers, who they had previously seen as allies, they lashed out at them as well. A few NGOs including the Kenya Human Rights Commission backed up NASA’s allegations to varying degrees, which then raised further fears of state repression (and generated further bad press internationally) when the state briefly tried to shut them down immediately the result was announced.

However, Odinga and the other NASA principles came under intense domestic and international pressure to take the constitutional path, as their ambivalent, partial move to “the streets” to protest during Wednesday 9th – Sunday 13th August was escalating and several people (probably at least 28) had been killed, mostly by the security forces.

NASA followed up their allegations with a petition against the presidential election, filed just within the one-week deadline on 18 August. Until the 16th, they had told Kenyans that “filing a petition at the Supreme Court to challenge the results was out of the question” because of CORD’s difficult experience in 2013 in crafting a case in one week, and the high burden of proof then demanded. However, Odinga and the other NASA principles came under intense domestic and international pressure to take the constitutional path, as their ambivalent, partial move to “the streets” to protest during Wednesday 9th – Sunday 13th August was escalating and several people (probably at least 28) had been killed, mostly by the security forces. Fears of broader communal violence in Nairobi were growing, fuelled by a series of fake media photographs, pretending to be current and of Kenya, designed to incite hatred. The decision to petition offered a temporary release for that tension.

For just one week (extraordinarily brief because of the two-week end to end deadline for concluding presidential cases, which the judiciary had already asked unsuccessfully to be extended) the Supreme Court heard the NASA case and responses from the IEBCs lawyers and other interested parties, with the verdict announced 1 September. NASA’s case focussed on five main areas – the electronic vote transmission system and its potential hacking (with the extraordinary claim that the portal results were a mathematical calculation unrelated to the actual votes cast); the missing form 34As and whether some were invalid or had been faked or substituted and errors in the KIEMS data entry which sent some of the results to the tallying centres; whether the IEBC Chairman should have declared without all the form 34As in his possession; examples of tallying errors between form 34As and Bs and possible malpractice in particular constituencies; and the pre-poll electoral environment including campaigning by Cabinet Secretaries for the ruling alliance.

The two dissenting judges’ Ndung’u and Ojwang’s opinions on the case were brutal – that the petition was without merit, devoid of evidence and that any transmission irregularities did not and could not have affected the outcome of the actual election at the polling stations or the count at constituency tallying centres.

To some surprise, by a 4-2 majority verdict the Supreme Court led by Chief Justice Maraga nullified Kenyatta’s re-election, because the poll was “not conducted in accordance with the Constitution”, and specifically the IEBC had “committed irregularities and illegalities inter alia, in the transmission of results”. The detailed grounds for that decision are not yet known, as the formally argued verdict will only be issued in 21 days (as it was “not humanly possible” in the words of the CJ to prepare the report in the time available). The court found no evidence of misconduct by Kenyatta (which had been one of Odinga’s petition grounds), though again we do not yet know their reasoning. It ordered another “fresh” presidential poll to be held in 60 days.

The two dissenting judges’ Ndung’u and Ojwang’s opinions on the case were brutal – that the petition was without merit, devoid of evidence and that any transmission irregularities did not and could not have affected the outcome of the actual election at the polling stations or the count at constituency tallying centres. Justice Ojwang argued that “there is not an iota of merit in invalidating the clear expression of the Kenyan people”. Kenyatta’s lawyers were furious, with one calling it “a political decision that is absolutely devoid of an iota of legal reasoning”, but the Supreme Court is Kenya’s final court and there is no further appeal.

Where were the Real Issues?

The single most vexed element of the whole election proved to be the electronic vote tallying and reporting, which had been introduced in the 2016 and 2017 Elections Act amendments. The unsolved murder of the IEBC expert responsible for KIEMS just before polling day (the reasons for which have still not been explained, though at least one person is still in custody) added fear and uncertainty to an already confusing situation. Most of this was unnecessary, as the election results used to calculate the Presidential winner should always and only have been those from the form 34Bs. The electronic results which came direct from the 40,833 polling stations to the portal were unofficial, incomplete (because they would and could never get 100% electronic results in a country so large and diverse economically as Kenya) and would inevitably differ (as they in fact did) from the 34Bs prepared at constituency level (mostly due to data entry errors into KIEMS by officials when transcribing manually from the completed forms). Repeated NASA allegations of hacking of the central IEBC server did not make great sense once it was clear that the central IEBC system was only being used for parallel presentation of polling station results from KIEMS. The actual presidential result came from the 290 constituency Form 34Bs. And the allegedly hacked portal had almost exactly the same result (8.2 m to 6.8 m) as that produced by adding the Form 34Bs.

The second significant concern was the delays in obtaining and then displaying the form 34As in IEBC headquarters. These were not (in the IEBC’s view) required for the central presidential announcement, but were still essential in order to determine whether the overall election was free and fair. No constituency RO should have announced their winners without all their form 34As, yet a week after they had finished, thousands were missing. The IEBC originally promised that “The results for the presidential election will be transmitted together with an image of the polling station tally sheet”. Then two days before polling, they announced what had already been widely suspected – that 11,000 polling stations did not have sufficient wireless network coverage – so the results from KIEMS would either come later or minus the scanned Form 34A copy. The whereabouts of these 11,000 forms became a huge problem. The IEBC was ambivalent and even misleading at times in its reporting. It seems they had not initially realised that the ‘one-time use’ model for KIEMS devices meant that for the polling stations where the system could not send the image but could send the results online, the scan of the form 34A would have to be provided much later by other means. These trickled in over the next 1-2 weeks, electronically or by hand. The IECB’s ambiguity over the 34As and the portal cost them dearly in perceptions of their competence and credibility.

Their failure to provide a display portal for the Form 34As and Bs was a mistake which was rectified, quickly for the Form 34As, and then grudgingly, a week after the vote, for the 34Bs. However, once done, it exposed gap between image and reality, when huge swathes of form 34As were found to be missing and some to be illegible. Those which were in the system matched well with the results in the online portal, but some were unsigned, unstamped or in a different format, and no-one knew what had happened to those which were missing. Some reports suggested the gaps were politically material (e.g. disproportionately from Odinga’s homelands).

It now appears that some media houses were ordered not to report on constituency contests, which might lead to suspicion that something deeper was amiss.

This linked to a more systemic concern – the back office operation of IEBC headquarters. While on the face of it, Wafula Chebukati, Ezra Chiloba and other commissioners maintained a relaxed face, and the portal and forms systems worked well, exactly where the portal results were coming from and why so few Form 34As were available has never been fully explained. It seems that administratively things were far from smooth in the back office. Basic security controls were lax, with IEBC staff frantically updating systems with whatever data they could get using various userids, some of their much vaunted document security features were invalid, key constituency documents were duplicated or unsigned and some officials were not even gazetted. There are still no published results apart from those on the portal for any of the other elections – no Form 35,36 ,37 and 38 for the parliamentary, gubernatorial, women representative or senatorial results have been published anywhere. The IEBC portal has results, but they are still incomplete nearly a month after the election, and differ from the (fragmentary) official results gazetted by IEBC on 18 August. In general, the results reporting and display process was unclear and IEBC did not always follow the procedures it had promised pre-election to ensure transparency and build confidence. The evidence from NASA’s petition showed numerous data and quality integrities, which while they were modest in individual impact and probably affected all candidates (and therefore would have limited material effect on the election result) certainly led many to question what was happening behind the scenes.

Another concern (less widely known) is the way in which the Kenyan media focused entirely on the electronic portal for their results, making no effort to report the actual constituency results. No independent tally was maintained and for the first time ever the press did not report any Constituency presidential, parliamentary or other results as announced. Initially I has thought that was simply practical laziness – since the portal was available and online – but it seemed inexplicable that the media were not reporting any of the announcements at all. It now appears that some media houses were ordered not to report on constituency contests, which might lead to suspicion that something deeper was amiss.

Still more concerns existed as to how individual presiding and returning officers behaved during their counting and tallying. Some Presiding Officers (for example in Mandera) were replaced the night before polling for unclear reasons. In some stations in pro-Jubilee homelands, NASA agents were not admitted and there was evidence in some stations of “top up” marking of unused ballots after polls closed. Many of the Form 34As had arithmetical issues or were not appropriately signed. It seems from NASA’s petition that some 34As may have been substituted with new (fake) documents or amended after counts finished (though KIEMS should prevent that, KEIMS didn’t work everywhere). In 13 per cent of polling stations, ELOG reported that Form 34A results were not displayed publicly as required by law. Some Form 34Bs show basic mathematical errors. There is also statistical evidence that (as in previous polls) presidential tallies were somehow inflated in the homelands (though there were few public protests at the time). For example, work in progress by Raiya Huru looking at the statistical distribution of Form 34A numbers suggests that in Murang’a, Nyeri, Nyandarua, Siaya, Kisumu and Homa Bay, the polling station results had been tampered with by someone (http://raiyahuru.com/Analysis.pdf). This matched well the NASA petition analyst’s view that something was amiss statistically with many of the results. The IEBC admitted that there were errors in the forms, but claimed they were not substantial enough to affect the outcome of the election.

The Presidential Election Part II

As the petition proceeded, life had begun to return to normal. The new MPs had been sworn in, governors had mostly completed their handovers, and for most Kenyans, the lengthy, expensive, diverting election was becoming a thing of the past. However, with the Court’s announcement we are now in uncharted waters, with the IEBC required to rerun the presidential poll within 60 days, for reasons which are not yet clear.

The IEBC should have been prepared for a runoff, so in theory all should be ready for a rerun. However, whether the IEBC can put together the temporary staff, the KIEMS devices, the logistics and the ballot papers in time for 17 October we do not yet know, especially as the IEBC itself is now under threat. So far Chebukati is staying put rather than resigning, but Chiloba has been side-lined entirely, as have several other officials (putting further stress on those who remain). But NASA is already objecting to the Supreme Court’s order that IEBC conduct a fresh poll in 60 days (because IEBC must be reconstituted), and IEBC has already decided not to conduct a full presidential poll anyway but only a second round runoff, based on the judgement in the 2013 petition [para 291] that “If the petitioner was only one of the candidates, and who had taken the second position in vote-tally to the President-elect, then the “fresh election” will, in law, be confined to the petitioner and the President-elect.”. And the precedent set in the Presidential petition would appear to allow every loser in the other five elections to annul every winner’s election on the same basis, if they can file a petition in time. So, more court cases loom while time runs out.

How effectively the two alliances will respond – without much time to raise money – to the need to do it all again no-one knows, but Jubilee are now grim, angry and spoiling for a rematch, which may well be dirtier than the first. My first guess would be that the result of the second election, if actually held, will be similar to that in the last, and in all the other “down ballot” elections, but until we know the real reasons why the Court annulled the vote, we do not know how much impact the irregularities they found may have had on the first presidential result. Victory in the courts may give the NASA camp fresh impetus and mitigate the pro-Jubilee bandwagon effect of incumbency, but Jubilee have a huge regional advantage (as they always did), more money and no intention of losing.

I had thought this would be my last piece, but perhaps we will need one more.