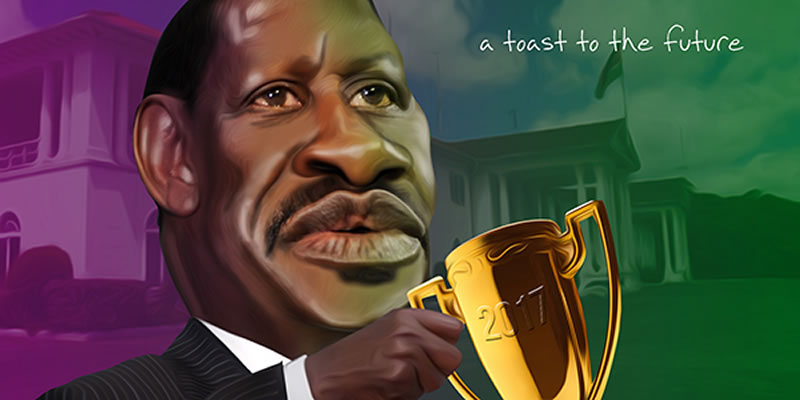

For the second time in as many elections, presidential candidate Raila Odinga has taken his case to Kenya’s highest court, the Supreme Court, alleging that he was robbed of victory. Four-and-a-half years ago, he grudgingly accepted the verdict of the six judges who ruled on his petition and who dismissed every issue he raised. Their written judgement has been excoriated across the globe for its shaky reasoning and privileging of procedure over substance. So, can Raila expect the court to be any more inclined to give him a better hearing this time?

There are significant differences between the current and the 2013 Supreme Court. By 2013, the court had already lost its Deputy Chief Justice, Nancy Baraza, to an ill-advised public altercation with a security guard reportedly involving nose-grabbing and admonitions to “know people”. The obvious effect of this was the risk of a hung court, with three justices voting each way, a situation that appears unforeseen and unaddressed by our constitution. Thus this may have been a significant consideration for the relatively young court and may have contributed to the absolute unanimity of the 2013 decision.

The 2013 judgement was a kick in the teeth, not just for the Raila campaign, but for the 2010 constitution and many of the progressive principles underlying it. And, as lawyer Wachira Maina described it, the judgement was “both detailed and important, but the parts that are detailed are not important and those that are important are not detailed.”

This time, however, the full complement of seven judges is available. However, it not the same bench. Two of the judges who heard the first petition have since left the court, some of them kicking and screaming and at least one under a cloud of suspicion. Kalpana Rawal, who replaced Baraza as the Deputy Chief Justice, promptly sued her employer, the Judicial Service Commission (JSC), to try and avoid being forced to retire at the age of 70, as specified in the constitution. It became an unseemly, farcical case that made its way to the Supreme Court, where she sat as a judge and which was riddled with conflicts of interest – some of the judges were themselves due to retire; others, such as the Chief Justice Willy Mutunga, were members of the JSC.

At the same time, Justice Philip Tunoi, who was among the Supreme Court judges fighting to forestall retirement, found himself embroiled in accusations of having taken a Sh200-million bribe in a petition against the election of Nairobi Governor Evans Kidero. A tribunal appointed by President Uhuru Kenyatta (following the JSC’s recommendation) to look into Tunoi’s suitability for office, however, had to wrap up its investigations prematurely after he was compulsorily retired by the recusal of Mutunga and Justice Smokin Wanjala from the Rawal case, which left no quorum.

Further, the court’s privileging of procedural rules rather than the substance of the dispute, as when it threw out Odinga’s 800-page affidavit that contained the meat of his case, as well as its reliance on questionable precedents from Nigeria (not exactly a bastion of democracy), also represented a huge step backwards.

Although only four veterans of the 2013 petition remain, it is unclear whether the court has recovered from the largely self-inflicted wounds to its credibility. Further, there is one sense in which the Supreme Court is itself constitutionally illegitimate. And that is because its composition falls afoul of the constitutional principle that “not more than two-thirds of the members of elective or appointive bodies shall be of the same gender”. As it stands today, five of its seven judges are men, which is more than two-thirds. This, therefore, raises the question whether the court can enforce a constitution it so blatantly violates.

Another example of unconstitutional conduct by the court is the fee it has imposed for the filing of a petition. The Constitution is clear that “the State shall ensure access to justice for all persons and, if any fee is required, it shall be reasonable and shall not impede access to justice.” Yet the Supreme Court requires that anyone exercising the right to challenge the presidential election pay a fee of Sh500,000 and deposit a further Sh1 million with the court as security for costs. Although this may not be much of an inconvenience to the super-wealthy NASA principals, in a country with an average annual per capita income of Sh100,000, it clearly “impede[s] access to justice” for the vast majority of the population.

However, there is another legacy of the first court that the current one still has to overcome, and that is the legacy of the 2013 judgement itself. In many ways, if it is to deliver a credible judgement, the court will have to confront and correct the deficiencies of that judgement. As Odinga said, it is an opportunity for redemption.

The 2013 judgement was a kick in the teeth, not just for the Raila campaign, but for the 2010 constitution and many of the progressive principles underlying it. And, as lawyer Wachira Maina described it, the judgement was “both detailed and important, but the parts that are detailed are not important and those that are important are not detailed.”

Importantly, the court subverted the idea of accountability by placing onerous burdens on the petitioners, rather than on the state, to prove what went wrong. This cannot be how the constitution conceptualised citizens’ relationship to the government. It generally should be enough for citizens to show that there is good cause for them to be suspicious of the state and up to the latter to demonstrate that what it did was both legal and proper.

The constitution was the culmination of a decades-long struggle to, in the words of John Harrington and Ambreena Manji, “tame the Kenyan Leviathan”, the authoritarian colonial state that had survived independence and nearly every attempt since to reform it. Throughout, the courts had been a central pillar in protecting the state from the people, almost always deferring to the wishes of the executive. “This deference was manifest, sometimes in outright bias, more often in a resort to procedural rules, denying citizens standing to hold the authorities to account.” The 2010 constitution was meant to reverse the concentration of power in the national executive and to make it more accountable. However, “rather than taming Leviathan the tendency of the [2013] decision has been to restore several of its key features.”

For example, the standard of proof established in the decision was onerously high. As Manji and Harrington stated, “All told, the Court has presented petitioners in presidential cases with almost insuperable obstacles of proof. The judgment casts them in the role, not of concerned citizens pursuing good governance, but as hostile prosecutors, charging the executive with culpable incompetence or serious criminal conduct and required to prove all elements of their case to the highest standard more or less… The effect of Court’s ruling in the immediate context is to insulate both the IEBC [Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission] and the candidate which it declares to have won on the first round from effective challenge in almost all cases.”

The court also appeared to require that Odinga and his fellow petitioners not only prove that there were irregularities in the election, but also that, beyond reasonable doubt, without these irregularities, he would have won. As Maina notes, “The law as borrowed from Nigeria, combined with the new standard of proof, leads to this absurd result: Mr. Odinga could show that the irregularities were so gross that everything about the election is in doubt [but that] would not necessarily be to his benefit.” If the election was so impugned that one could not prove beyond reasonable doubt who won, “the result announced by IEBC would stand. This, surely, cannot be good law.”

Importantly, the court subverted the idea of accountability by placing onerous burdens on the petitioners, rather than on the state, to prove what went wrong. This cannot be how the constitution conceptualised citizens’ relationship to the government. It generally should be enough for citizens to show that there is good cause for them to be suspicious of the state and up to the latter to demonstrate that what it did was both legal and proper.

Odinga will be taking his case to the people, whose judgement will matter much more than that of the judges. There, burdens will be reversed. It will be the IEBC and Kenyatta on trial; they will have to demonstrate the propriety of their actions and, thus, of their claim to legitimacy.

Further, the court’s privileging of procedural rules rather than the substance of the dispute, as when it threw out Odinga’s 800-page affidavit that contained the meat of his case, as well as its reliance on questionable precedents from Nigeria (not exactly a bastion of democracy), also represented a huge step backwards.

Even the delivery of the judgement itself was wanting, with Chief Justice Mutunga opting not to read all of it in open court but rather delivering the verdict with a promise to avail the reasoning behind it within a fortnight. It thus seemed like either the judgement was too embarrassing to read out in its entirety or that the verdict came first and the reasoning later. The seeming privileging of unanimity also meant that the judges did not contribute individual judgements and thus we were unable to interrogate their individual reasons for coming to the conclusions that they did.

The rub of it is that, if followed, the precedent set by the 2013 decision virtually guarantees that the court will never reverse the IEBC’s declaration of a winner in the presidential election, especially not if that declaration is made in the first round. It is thus exceedingly unlikely, though obviously not impossible, that the second Odinga petition will fare any better than the first. However, that does not mean it is an exercise in futility. For there is another, much more important court he will be presenting his evidence to.

If the last time is anything to go by, every word of the proceedings will be broadcast to an attentive audience of millions of Kenyans. Odinga will thus be laying out his evidence not just for the benefit of judges in the sanitised environment of a court room but also to the fervent, anxious, speculative and intensely polarised country beyond. Odinga will be taking his case to the people, whose judgement will matter much more than that of the judges. There, burdens will be reversed. It will be the IEBC and Kenyatta on trial; they will have to demonstrate the propriety of their actions and, thus, of their claim to legitimacy.

He will not only dispense with the easy and thoughtless monikers, such as “perennial loser”, but will in the process fatally undermine Kenyatta’s authority. His petition will thus provide the necessary oxygen for any campaign of civil disobedience and peaceful protest that he may be inclined to pursue in a bid to either recover his rights or to push for further reform.

Legal declarations can bequeath power, but only the people can offer legitimacy. And it cannot be coerced out of them, whether through beatings, intimidation or even murder. It can only be given voluntarily. The election is just a way of attempting to entice it out of them. But for too long, the state has violated the bargain and tried to subvert the will of the people by stealing elections. In his testimony before the Senate last year, Samuel Macharia, the owner of Royal Media Services, the country’s largest TV and radio network, said he had evidence that every presidential election in the multiparty era, except the 2002 one, had been stolen.

So, while winning the election has some value, the legitimacy it is said to confer is dubious at best. By appealing directly to the people, Odinga will be seeking their endorsement to erode Kenyatta’s. If he succeeds, regardless of whether the Supreme Court still rules against him, his legacy will be secure as “The People’s President”. He will not only dispense with the easy and thoughtless monikers, such as “perennial loser”, but will in the process fatally undermine Kenyatta’s authority. His petition will thus provide the necessary oxygen for any campaign of civil disobedience and peaceful protest that he may be inclined to pursue in a bid to either recover his rights or to push for further reform.

And even though, like his father, Odinga never got to govern the neocolonial Kenyan state, his struggle in the Supreme Court will further undermine the state’s legitimacy and bring Kenya closer to the day when it is eventually overthrown.