On June 2, 2010, the then Speaker of the National Assembly Kenneth Marende declared the Makadara seat in Nairobi vacant. The MP, the late Dick Wathika had lost the seat after a successful petition by Rueben Ndolo, a former holder of the seat (2002—2007). The by election was slated for September 20, 2010.

Three weeks to the by election, I had an interview with Wathika — popularly known as Mwas, his mtaa (estate) nickname — at a posh Nairobi hotel. He was in his element: exuding an unusual confidence. He boasted to me how he was going to wallop yet again his opponent Ndolo, who was contesting on an ODM ticket.

Finding him vain, I reminded him the fight was no longer between him and his known adversary, but was now going to be a three-pronged battle, which in my view, needed a different tact and strategy. A third contestant had entered the fray and his name was Gideon Mbuvi Kioko alias Mike Sonko.

“Wewe Dauti ni nini sasa…kwani umesahau kule tumetoka?” (You Dauti what’s up with you? You’ve forgotten where we’ve come from?), he chided me. “Huyo ni nani unaniambia stori yake. Ndolo ndiye opponent wangu. na nitam KO.” (Who’s that you telling me about? My opponent is Ndolo and I’ll knock him out). Wathika, in his heydays, just like Ndolo was an amateur boxer, the only difference being Ndolo had taken his boxing a notch higher and fought as a professional.

Mwas could afford to get up close and personal with me, because I had known him since childhood. We had grown up together in Maringo estate. In 1991, after former President Daniel arap Moi had repealed the infamous Section 2(a) of the old constitution, multi-party politics had returned to the fold.

The following year, Wathika joined politics through the Ford Asili party which had split from Forum for the Restoration of Democracy (FORD), the first opposition party formed after the political liberalization. Kenneth Matiba formed Ford Asili, while the then doyen of opposition politics Jaramogi Oginga Odinga formed Ford Kenya.

As luck would have it, Mwas was a boy wa mtaa (local boy), all the electorate; young and old who had desired change voted for him and he run away with the popular vote. Wathika was elected as the Maringo ward councillor — defeating the KANU incumbent, Kiura Kirandu — hands down.

Wathika had had a great run as a politician from 1992, when as a 19-year-old elected rookie, he become one of the youngest minted multiparty party era politicians. In between 1992—2010, he had served three terms as a councillor, a mayor for two years and an MP for two and half years, including a stint as Assistant Minister for a year and four months. But his streak of luck would suddenly end with the arrival of Sonko.

Sonko, shot to political prominence, when he was first elected to parliament as Makadara MP on September 20, 2010. To the utter surprise of Wathika and Ndolo, Sonko, then 35 years old and running on a Narc Kenya ticket, caused a major upset by polling 19,535 votes against his closest rival, Ndolo’s 16,613.

Wathika, the incumbent pooled a poor third. “I must admit I did not see the defeat coming…I had had it too easy,” he was later to tell me when we again met in December 2010.

The entry of Sonko into the abrasive city politics immediately did two things: He sent Wathika packing — first to an emotional declaration of quitting politics altogether, and after he had recollected himself, into exile in Mukurweini constituency in Nyeri County. Sonko also confined Ndolo to ODM party politics. Within two and a half years, Sonko was transformed from a political neophyte to a juggernaut.

By March 2013, he was so confident he had outgrown his parliamentary seat, he threw his force into contesting the newly created senator seat. He won the Nairobi senator seat by the biggest number of votes cast for any senator or governor countrywide. Running against his closest competitor Margaret Wanjiru, he polled 808,705 votes against the burly priestess’ 525,822 votes.

In Nairobi County, Sonko proved to all and sundry he was the king of politics. Running on The National Alliance (TNA) party, he polled even more votes than either his party boss, Uhuru Muigai Kenyatta, who got 659,490 votes, or he latter’s rival, Raila Amolo Odinga, who received 691,156 votes. It was evident that Sonko had stomped the city politics like no other and, any politician who ignored him could only do so at their own peril.

Who is Sonko and how is it that today he is the most talked about politician, only after President Uhuru Kenyatta and the leader of Opposition Raila Odinga?

Sonko appeared on the Nairobi scene in the early 2000s just like in the movies: with a bang. One day, Nairobian woke up to the sleekest No. 58 matatus operating on the Buru Buru Phase V, IV and III estates’ route. Sonko had invested in a fleet of matatus that came to be known as nganya — a super pimped matatu — a superlative of manyanga, which is an ordinary pimped matatu.

His crew staff did not disappoint: His drivers and conductors were the whippiest lads you could find anywhere in the matatu transport industry. They were funky and wore the latest fashions. Equipped with the latest hi-fi music systems complete with woofers, Sonko’s matatus could be heard a kilometre away.

Within two and a half years, Sonko was transformed from a political neophyte to a juggernaut.

The naming of his matatus completed the picture and in a somewhat subtle way, told Sonko’s own shady story. They bore names such as — BROWN SUGAR, CONVICT, FERRARI, LAKERS and ROUGH CUTS. His matatus were so hip, trendy Buru Buru schoolkids would not board any other matatus.

Sonko’s investment in the matatu industry has been surrounded with a lot of mystery and allegations of money laundering. He entered the industry with a great deal of razzmatazz, buying many matatus at one go and for a while, the quiet talk among his fellow matatu owners was that the source of his wealth was the illegal drug trade.

Indeed, the late Minister of Interior Security, Prof George Saitoti in December 2010, named him in Parliament as one of the country’s drug lords. Talking to one of his close buddies recently, he reiterated that Sonko has never been taken to court over that mention or the allegations that were swirling before and even after. “To the best of my knowledge, the mention by the late Saitoti about Sonko involvement in drugs, has remained just that: a mere mention, nothing, more…nothing less,” he said.

The source of Sonko’s wealth though has never been fully publicly explained. Years before, then known as Gidion Mbuvi Kioko, he was a middle man selling parcels of lands in the Coast region, where he had grown up.

Many a time, it is alleged, he would take off with all the money after a land sale. In 1997, he was accused of having falsified documents relating to land belonging to Eliud Mahihu, the former all-powerful Coast Provincial Commissioner during Mzee Kenyatta’s era.

Two years after he was arrested and taken to Shimo-la-Tewa Prison, it is said he smuggled in cash in a briefcase into the prison, which his acolytes had passed onto the prison warders. They, in turn, are said to have facilitated his escape after he was taken to Coast General Hospital feigning a range of ailments — from epilepsy, HIV/AIDS to Typhoid. Later, in mitigation, Sonko was to argue that he had run away from jail to attend his mother’s funeral.

Just a few years later, Sonko was hanging around then Wab Hotel, at the Buru Buru shopping centre, clad in denim jeans and a T-Shirt, chatting away the boys. His matatus then employed an upward of 50 youth.

The naming of his matatus completed the picture and in a somewhat subtle way, told Sonko’s own shady story. They bore names such as — BROWN SUGAR, CONVICT, FERRARI, LAKERS and ROUGH CUTS.

In January 2003, after the National Rainbow Coalition (NARC), an alliance dislodged the ruling KANU from its 24-year-old stranglehold of power, President Mwai Kibaki appointed the late John Michuki as the Minister of Transport. Michuki was used to getting his way — from his days as a colonial administrator in the 1950s, when he was a district officer in Nanyuki, up to even when he entered politics. The “Michuki rules” which he initiated immediately he assumed the transport docket and which quickly resonated with the people, remained a diktat, until Sonko went to court in 2006. Sonko won his case because, as the High Court reminded the Transport Ministry, without official publication in the Kenya Gazette, the rules were just that: Michuki “personal rules”. It was only after the court case that the rules were now formally gazetted.

One of Michuki’s more infamous edicts was that of barring matatus from entering the central business district of Nairobi. It was a clearly selfish decree because of the conflict of interest that arose from an exception to the rule, allowing in vehicles belonging to the City Hoppa matatu company in which the Minister had invested heavily.

Sonko, whose matatus were affected by this unlawful rule, went to court. To the surprise of many, he won the case after a protracted battle. His matatus were allowed back into the city centre, along with a select few from other owners. The judicial victory improved Sonko’s standing among his employees and followers, who viewed him as their “Mr fix it”.

But more significantly, it, catapulted him to the chairmanship of the then amorphous and now defunct Eastlands Matatu Operators Association. The position gave Sonko influence and power commanding then close to 8000 matatus.

From being the darling of the youth, he became the darling of the masses. The passengers who used to be dropped off at the dusty Muthurwa, and who would then have to trek to the city centre — there were no boda bodas at the time — could not thank him enough. It was just a matter of time before he moved to the next level. When the Makadara constituency election was nullified by the High Court in April 2010, an opportunity availed itself and Sonko seized the moment and ran with it.

After becoming MP, Sonko sought to endear himself to his constituents. He would engage the City Council to get his constituents exempted from paying parking fees within Makadara constituency. The court injunction was only temporary but he had made his point: he would always be ready to fight for his people. For a while, he also made it tenuous for slum lords to arbitrarily evict tenants. He would go to court on behalf of the tenants and file a case.

On Sunday March 19, 2017 on national TV, Sonko ranted against Peter Kenneth, then one of his more formidable opponents for the Jubilee Party ticket for the Nairobi gubernatorial contest. From the onset, it was evident in the interview Sonko pulled no punches and held no prisoners when describing Kenneth. His apparent contempt for the former presidential candidate was palpable.

Two years after he was arrested and taken to Shimo-la-Tewa Prison, it is said he smuggled in cash in a briefcase into the prison, which his acolytes had passed onto the prison warders.

The 51-year-old Kenneth would later quit Jubilee Party, after losing the nomination battle to Sonko, to run as an independent candidate. He came off as a sore loser who had expected his path to the nomination to be smoothened for him. And therein lay his Achilles Heels: entitlement. Listening to him explaining his tribulations, Kenneth inadvertently casts himself as a “choice candidate” who was owed and had been let down by the Jubilee Party cabal at the Pangani headquarters.

But more than giving the implicit impression that he was the favoured son, Kenneth has been unable to shake off the label of being a “political project” or a front for other interests. First, he was a project of the “Murang’a Mafia”. Now, he is viewed as a “Governor Evans Kidero project”. It cannot get worse.

Yet, the project tag is not the only label he is struggling with. When Sonko first taunted him as a foreigner and a Johnny-come-lately to city politics, Kenneth laughed it off and made light of the remark by pointing out that even when he represented Gatanga constituency, he slept in Nairobi.

The bad news for Kenneth is that this refuses to go away. “Peter Kenneth is a foreigner to Nairobi politics”, says a Nairobi lady restaurateur known as Wa Carol. “Where has he been for four years?” the restaurateur, who herself voted for Sonko during the nominations, muses loudly. His goose was cooked the day he announced he was running in Nairobi, she says.

“After PK first announced his bid in January, Maina Kamanda afterwards came over and addressed us Kikuyu business people in Nairobi and told us: ‘we need someone to protect our property and the man to do precisely that is Peter Kenneth’. I thought Kamanda was kidding me. I do not own any property in Nairobi”, says the lady who is in her late 40s.

It is the same reaction that my friend, Elvis Kinyanjui, who has been a street vendor in the CBD for the last three decades, had: “Kamanda is talking of protecting property — whose property?”

The Peter Kenneth who ran for presidency in 2013 is radically different from the man seeking to be the governor of the capital city. In 2013, he projected himself as a de-tribalised, smooth and urbane Kenyan — the poster child of cosmopolitanism with refined features. Barely four years later, he agreed to be repackaged as a Kikuyu sheriff coming to the city with a mission to rescue a propertied class ostensibly under siege.

Pitted against a man — Sonko — who has carved himself a niche as the spokesman for the city’s underclass and defender of their trodden rights, Kenneth’s apparent aloofness and association with the moneyed class casts him as removed from the everyday struggles of the city dweller.

Listening to him explaining his tribulations, Kenneth inadvertently casts himself as a “choice candidate” who was owed and had been let down by the Jubilee Party cabal at the Pangani headquarters.

In the nominations that he has bitterly disputed, Kenneth was walloped by Sonko, 138,185 votes to 62,504. Could Sonko have wrestled the power and glory from the Murang’a business elite’s grip on Nairobi, thereby redefining the politics of Nairobi?

Nairobi city politics have always been under the grip of Kikuyu business and political elites save for two major periods — between 1969 to 1970 and 1983 to 1992. In 1969, Isaac Lugonzo took over from Charles Rubia and in 1983, former President Moi disbanded the City Council when Nathan Kahara was mayor to form several commissions till the return of multiparty politics in 1991.

From way back in the 1960s, when the first Minister of Trade and Commerce was Dr Gikonyo Kiano, who like Rubia, the city mayor, hailed from then Murang’a District, the city’s business allocations and licenses tended to favour the Kikuyus from Murang’a. That is why, it not a coincidence that many of the city business godowns in the industrial area are owned by Murang’a tycoons. That is also why many of the buildings in downtown Nairobi, especially on River Road and Kirinyaga Road, are owned by the famous Rwathia group, which has its origin is in Rwathia in Murang’a.

Similarly, many of the small traders — from hawkers to street vendors— are Kikuyus from Murang’a many of whom are today settled in Starehe constituency. It is equally not a coincidence that Maina Kamanda, another Murang’a supremo, started his political career at Ngara West Ward (one of the wards that make Starehe constituency), eventually running for the parliamentary seat. The ward, and indeed the entire Starehe constituency, is populated majorly by Kikuyus from Murang’a.

“The thought of Sonko running the affairs of the biggest economy outside the national government at the City Hall is just frightening”, the earlier quoted businessman confided.

After the re-introduction of multiparty politics, the position of the mayor may have been whittled down, but still, Kikuyu political mandarins controlled the mayoral seat, if not directly, then indirectly. Between 1992, after the first multiparty elections and 2002, the mayors were all Kikuyus. From Steve “Magic” Mwangi, John King’ori, Sammy Mbugua, John Ndirangu to Dick Waweru, whose second term ended in 2002.

The only other time a non-Kikuyu was boss at City Hall was between 2003—2004 when Joe Aketch, a nominated councilor, was mayor. Aketch owed his mayoral seat to Kamanda. The vicious infighting between the Kikuyu councillors at City Hall that ensued after the Narc victory, forced Kamanda, the newly elected Starehe MP, to throw his weight behind Aketch’s candidacy.

Geoffrey Majiwa, then the Baba Dogo ward councillor was the Nairobi mayor after President Mwai Kibaki and Raila Odinga formed the grand coalition government in 2008. George Aladwa served between 2010—2012, after he took over from Majiwa, who had to step aside after he was allegedly implicated in a cemetery land corruption scam. Following the 2013 election, which rung in new constitutional arrangements, especially devolution, Evans Kidero, a Luo, defeated his Kikuyu rivals to clinch the Governorship.

Still, of the 15 mayors Nairobi had between 1963 and 2012, only 4 were non-Kikuyu. Many Kikuyus have therefore come to regard Nairobi city as an extension of Kiambu County due to its proximity, notwithstanding the fact that Kiambu Kikuyus appear to have ceded control of the city businesses to their cousins from Murang’a. In March 2017, a Jubilee Party parliamentary candidate from Roysambu was interviewed on Inooro TV. When asked who should be the governor of Nairobi, his answer was curt. “A Kikuyu of course”. “Why?” posed the interviewer. “We Kikuyus are the owners of the city”.

This reasoning among the Kikuyus is buttressed by the notion that many of the city businesses and investments’ operations are run by Kikuyus. Also, because of the proximity of Kiambu and to a large extent Murang’a Counties, coupled with the fact that the first post-independent government of Mzee Kenyatta encouraged many Kikuyus to come to Nairobi, Kikuyus have always been numerically superior. According to some reports, one in three Nairobians is a Kikuyu.

Since Sonko declared his intention to run for the governor’s seat, a section of the city’s business community has become uneasy and wary of his burgeoning grassroots support across the city electorate. Towards the end of last year, Kikuyu businessmen in the city met and proposed a “sober and mature” person to run for the seat, in the hope of unseating governor Evans Kidero. “We had to act and come up with a name, in view of Jubilee Party’s apparent lack of a saleable candidate,” said one businessman who was privy to the meeting.

That is when they proposed Peter Kenneth. There is no gainsaying the fact the bulk of the most influential Kikuyu businessmen in Nairobi hail from the greater Murang’a County. Before, the carving out of additional districts from the original Murang’a largely by President Daniel Moi, Murang’a District began just after Thika town extending all way to the border of Karatina town, which is in Nyeri District. The urban and thoroughly cosmopolitan Kenneth is from Kirwara sub-location in Murang’a.

When the businessmen argued that they did not know where Sonko came from and what business he does, they were subtly saying he is not one of them. It did not matter that he is a Jubilee Party loyalist. “The thought of Sonko running the affairs of the biggest economy outside the national government at the City Hall is just frightening”, the earlier quoted businessman confided. To calm the Murang’a Mafia fears and sooth their egos, Sonko has picked a mid-career corporate professional, Polycarp Igathe, who hails from Murang’a County as his deputy.

I was informed that Sonko oftentimes sneaks in at night to catch up with wazito — the gangland (heavy weight) leaders, who also boasted of having Sonko’s direct contacts.

Sonko’s mocking of academic papers during his high pitched monologues to Citizen TV host Mohamed Hussein — never mind he has himself rushed to get them — is a testament to how these credentials have come to mean nothing insofar as the governor’s seat is concerned. Dr Evans Kidero with his “excellent” academic papers and “management experience” and presumed “track record” has ensured that these qualifications will not be anything to brag about when canvassing for the governor seat’s votes.

Kidero’s rival was Ferdinand Waititu, a former MP of the larger Embakasi constituency. Waititu started off as a councillor for Njiru ward, which was then part of the constituency. He also deputized mayor Wathika. Waititu is always remembered for his “unparliamentary” behaviour of throwing stones and boxing his constituents.

Yet, in uncanny twist of fate, he outmanoeuvered his competitors to clinch the TNA party ticket. One of the more formidable candidates in the Nairobi governor seat elections in 2013 was one, Jimnah Mbaru who ran on the defunct Alliance Party of Kenya (APK) after he failed to secure the TNA nomination. He performed dismally, coming a distant third.

Like Kenneth today, Mbaru had always been dogged by claims of being elitist and not “a man of the people”, since the first time he entered electoral politics in 1992, when he first ran for a parliamentary seat. Waititu’s chief campaigners in 2013 rode on that narrative to besmirch Jimnah. He was painted by Waititu as a man who would not soil his (well pressed) suits to get into the mud to help the people.

A cursory glance at Sonko’s city support base today quickly reveals a demographic stratum that comprises voters who care nothing about academic qualifications and management experience. Disenchanted with Kidero’s apparent lack of vision for the city — Nairobians were hoping for a makeover and an invigorated capital city — this voter bloc has all but dismissed these “elite” qualifications.

Four months ago, I conducted a reality check in Mathare constituency, one of Sonko’s electoral bastions. Mathare is made up of six wards. In Huruma, the “area boys” told me Sonko was their guy. No doubt. Speaking to me in that lyrical Sheng only spoken in the toughest of the city ghettos, the young men spotting crew cuts dismissed Kenneth as an “impostor”. “Huyo mlami alikuwa wapi hizo siku zote?” Where was the white man all these time? “Kenneth ni candidate wa mababi”. Kenneth is the city’s bourgeoisie choice.

Of course, Mathare is not Sonko’s only voter catchment area. The entire Eastlands area — including the Central Business District — is considered to be his political playground. From the City Stadium roundabout, the area sandwiched between Jogoo Road and Lusaka Road is populated with Sonko’s presumed loyal supporters. This area straddles basically four constituencies: Makadara, Starehe and Embakasi South and Embakasi West.

Still, of the 15 mayors Nairobi had between 1963 and 2012, only 4 were non-Kikuyu. Many Kikuyus have therefore come to regard Nairobi city as an extension of Kiambu County

In Makadara constituency, Sonko’s support is to be found in the larger Buru Buru, Ofafa Jericho and Jericho Lumumba, Maringo, Mbotela and Hamza estates. Add to these estates, Mukuru kwa Njenga slum. In Starehe constituency, Sonko’s biggest support base is in the Mukuru kwa Rueben sprawling slum which is adjacent to the other Mukuru and other scattered slums in the Industrial area. In Embakasi South constituency, his most ardent supporters are in the heavily populated Pipeline area. In Embakasi West, his supporters are to be found in Umoja I and II, Mowlem and Kariobangi South.

Separate from the Jogoo Road/Lusaka Road axis, Sonko also commands great support in the area between Juja Road and Heshima Road, which runs through Bahati and Jerusalem estates. This area mainly encompasses Kamukunji and Embakasi North constituencies. In Kamukunji constituency, his greatest support resides in Biafra, Majengo — popularly known as Kije — and Shauri Moyo estates. Majengo, one of the city’s oldest and most densely populated slums, is heavily Islamized and Swahilised — cultural traditions that Sonko easily identifies with and vice versa.

In Embakasi North, the sprawling Dandora areas I, II, III, IV and V, including Gitare Marigu ghetto are Sonko’s forte. Away from Eastlands, Sonko can also call support in Dagoretti South, a peri-urban and semi-rural constituency.

To the macho ghetto youth, the fact that Sonko spent time in prison, means he is a “made man”. “Sonko ni mtu alikuwa piri…na saa hii yuko wapi?” (Sonko was in prison…now look where he is).

Sonko’s penetration of these urban poor areas was facilitated by his supposedly philanthropic outfit; the Sonko Rescue Team, which would supply the one golden commodity that is scarce to many Nairobians, rich and poor — water. For many of these people, they did not need to see Sonko physically: The SRT vehicles would announce the presence of the unseen Sonko.

Invariably, Sonko’s supporters will not be voting for him because he is in Jubilee — his core constituency is to be found across the ethnic divide and would vote for him wherever he would take them. It is that simple. Nobody cares to remember that Sonko is a Mkamba from Mua Hills in Machakos County.

My street vendor friends — many of them Kikuyus and who ply their trade in the CBD, have told me they are rooting for Sonko. They believe he will be kinder to them. “Sonko ni mtu anaelewa works ya vijana.” (Sonko is a man who understands the struggles of the youth). “Yeye hukuja kutucheki na ametupromise ata deal na mabigi wa hii tao.” (He comes by to say hello, and has promised, he will deal with the city’s bigwigs).

Sonko won the street vendors’ favour, when he confronted the city askaris, who consistently and persistently harassed the vendors. Sonko had been consistently vocal about the violence at least since 2014, and in January 2016, three notorious city askaris, who have since been charged with a spate of murders involving street vendors, were arrested days after he threatened to resign.

Sonko has promised to put the city askaris firmly in their place, should he win. “Sonko alitushow atanyorosha hao makanjo.” (Sonko told us he will straighten up the city askaris — if he becomes the governor).

Typically, nearly all the boda boda riders who operate in the CBD are Sonko’s supporters. Like their counterparts, the street vendors, they regularly fall afoul of the archaic city by-laws, and hence are a perpetual target of harassment by city askaris seeking to extort bribes; oftentimes violently.

Sam Ochieng who is an Advertising Executive, says he will vote for Sonko. “Sonko animates politics in a way no other Kenyan politician does.” My restaurateur friend, Wa Carol, told me she will cast her vote for Sonko, because she believes he is a man of action and will be accessible. “Kidero is a total flop. All he did was to increasingly levy taxies on small enterprises without offering any services. Look at my restaurant’s backstreet: piles and piles of garbage…and every month we are required to pay service charge.”

Away from Sonko’s presumed multicultural support base, his ethnic city support is also as good as assured. It is not for nothing that Mukuru kwa Reuben and part of the Mukuru kwa Njenga slums are solidly behind Sonko: in the city politics’ parlance, they are Kamba ghettos. So is Biafra in Kamukunji, Mbotela in Makadara and Pipeline in Embakasi South.

According to Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) latest figures on the total registered voters, out of the city’s 2.3 million registered voters, 450,000 are Kambas, the second-largest voting block after the Kikuyus. With his entry into the governor’s race, Sonko has complicated the ethnic arithmetic for Evans Kidero/Jonathan Mueke ticket. The retention of Mueke as a running mate was essentially to tap and harvest this Kamba vote.

Three weeks ago, Johnstone Muthama, one of NASA’s fundraisers and campaigners called for a meeting at City Stadium, where every eligible Kamba voter had an automatic invitation. On the agenda: how to marshall Kamba support for Kidero/Mueke NASA ticket. Regardless, Hannah Mutiso from Buru Buru, told me her vote for the governor is for Sonko and so did Mbula from Pipeline in Embakasi South.

If the Kamba vote will prove to be problematic to Kidero, the Luhya vote may also not be automatic. A City County Luhya employee, who requested anonymity, confided in me that not all Luhyas will vote for Kidero. “We have not forgotten how he caused so much grief for our people when he was the boss at Mumias Sugar Factory.” Kidero has been variously accused of mismanaging and misappropriating the company’s finances, a charge that has yet to be proven in the courts, but which has refused to go away and sticks out of Kidero’s lapel like a rotten flower.

Sonko’s works of charity — though driven more by his need to shore up his votes rather than real philanthropy — in places like Kosovo, another of Mathare’s wards, are seen as actos of noblesse oblige in one of the riskiest slums in Nairobi. There, I was informed that Sonko oftentimes sneaks in at night to catch up with wazito — the gangland (heavy weight) leaders, who also boasted of having Sonko’s direct contacts.

Some of the philanthropic activities that Sonko continues to dazzle Nairobians with include paying school fees for some needy students and providing a free ambulance service. As MP, he claimed to have regularly purchased a geometrical set for every pupil in his constituency who sat for the Kenya School of Primary Education (KCPE) examination.

In six short years, Nairobi politics has seen Sonko capture the aspirations of the hoi polloi sequestered in the dangerous, horrid city ghettos, where in the true Hobbesian fashion, “life is short, nasty and brutish”. If his criminal record is supposed to stick out as a sore thumb, the contrary is true. The record, which he does not shy away from, has proved to be a magnet to the youth — who form the strength of his fundamental support.

To the macho ghetto youth, the fact that Sonko spent time in prison, means he is a “made man”. “Sonko ni mtu alikuwa piri…na saa hii yuko wapi?” (Sonko was in prison…now look where he is).

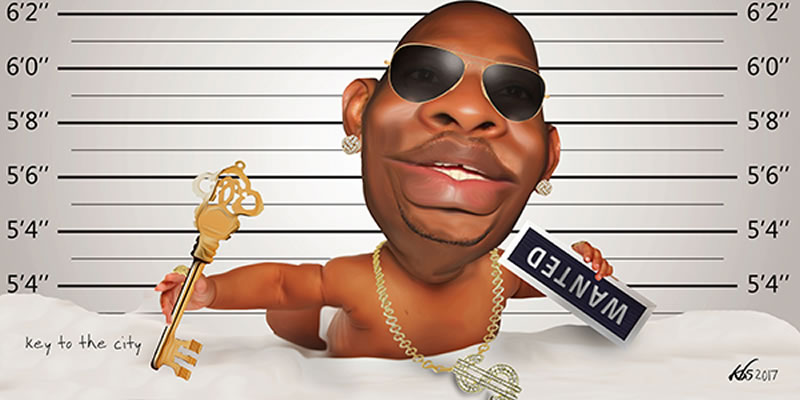

Cutting the figure of a flashy, flamboyant, jewelry-clad gung-ho, Robin Hood type of a Mafia don, Sonko popularised the street slang name — sonko — connoting a man of limitless wealth. Adored by the millennial and generation Z, whose every day dream is to be a sonko, like the real Mike Sonko, they are expected to come out and vote for him en masse.

Sonko who converses in the “rebel language” of the slum-trodden youth, has impressed on them that you do not need an education to live it up. In the process, he has “sonkonised” the politics of Nairobi.