Back in September 2016, I published a piece on Facebook that suggested, based on recent party dissolutions and mergers into Jubilee and the accompanying defections by numerous politicians, that – barring discontinuous events, such as the death of a senior leader – the August 2017 general elections in Kenya were already almost over and that Jubilee’s victory seemed assured. The key data I used was the publicly declared political affiliations of each incumbent constituency MP and governor. At the time, the Jubilee bandwagon looked near unstoppable, with two-thirds of the elected constituency incumbents then in their camp (compared to only half after the 2013 elections). Nine months have passed since then. With hindsight, how accurate does that prediction look today?

What follows is an independent, unpaid analysis. It is not sponsored or supported by any political party, and it makes no attempt to argue right or wrong, or to favour one alliance over the other; it is purely to assess the current situation and to make an educated guess as to the likely outcomes. As it contains predictions about the unknowable future, it will of course be wrong in many details. But Kenyan election results are far from random; they follow regular patterns and rarely exhibit discontinuous changes, and it is possible to make educated guesses about what will happen based on previous experience. This piece of crystal ball gazing assumes no sudden deaths or disbarments amongst senior leaders, and it doesn’t suggest these results are immutable. Most voters are pretty clearly spoken for, but there is still a sufficiently large “floating vote” to change the result.

Reading the Kenyan media, the answer to my question would seem to be “no”: my 2016 prediction of a Jubilee victory doesn’t look good at all. The opposition NASA has had an excellent 2017. Since the start of the year, it has formally brought Musalia Mudavadi’s Amani National Congress (ANC) and Isaac Ruto’s Chama Cha Mashinani (CCM) into the CORD alliance of ODM, Wiper and FORD-Kenya, creating NASA (The National Super Alliance). Its aim was to emulate the national alliance that created the National Rainbow Coalition (NARC), which defeated Uhuru Kenyatta in 2002 (and to respond to the creation of the Jubilee Alliance Party itself). It has also chosen its presidential and vice presidential candidates without mass defections among those who lost out. Energised by numerous real or imagined corruption scandals and by the recent food crisis, Jubilee has been on the defensive throughout. For example, the opposition took good advantage of the grand opening of the Standard Gauge Railway between Nairobi and Mombasa, intended to be a “signature” Jubilee achievement, by focusing on alleged corruption in its procurement, leaving Jubilee’s claims of service delivery looking hollow and unconvincing.

NASA’s choice of Raila Odinga and Kalonzo Musyoka as presidential and vice presidential candidate, respectively, was both logical and predictable, but also a conservative strategy that set the two candidates up for an exact reprise of 2013, with the same two frontmen on both sides.

However, a strong performance doesn’t yet mean victory. There are several reasons why my prediction back in September 2016 of a 55-45 victory for Kenyatta over the (yet to be chosen at that time) opposition candidate remains plausible.

Firstly, the opposition shunned the chance to play a different game, and faced up to Jubilee with exactly the same lead players as had fought and lost in 2013. NASA’s choice of Raila Odinga and Kalonzo Musyoka as presidential and vice presidential candidate, respectively, was both logical and predictable, but also a conservative strategy that set the two alliances up for an exact reprise of 2013, with the same two frontmen on both sides. On that basis, it is hard to see the result being materially different. For NASA, the opportunity to improve on their 42% performance in 2013 lies with the incorporation of much of Mudavadi’s vote (4% nationwide, mostly in western Kenya) into NASA. For Jubilee to improve on their 50% performance in 2013, it needs to leverage the power of incumbency, its deeper pockets, the resources it has allocated to specific communities, and the positive messages (hard to sell as they are proving) about their delivery to Kenyans during 2013-17.

Secondly, Jubilee is only just beginning to start campaigning in earnest, and has substantial resources in reserve. Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto are now touring nationwide, leading public rallies with exhortations to support Jubilee because of the (state) resources they have directed to local communities and the (state) jobs they have given to local elites in classic KANU-era style. At the moment they appear strangely uncertain and unconvincing in their message. But elections are not won on the campaign dais. There is much more work which can and will be done at the grassroots in parallel to target specific swing groups and persuade voters in those regions to stay with the “devil they know”. Jubilee is significantly wealthier than NASA, with a more unitary command structure and better campaign technical support. It has barely started to attack Odinga and Musyoka personally, and there is a huge amount of mud which could – and probably will be – thrown at NASA between now and August.

Third, Jubilee went into the primaries with the support of even more MPs than it had in 2016. Rather than mass defections to NASA, the stream has continued to flow (though more slowly) to Jubilee. Individual politicians can be both “leading” and “lagging” indicators, either encouraging their constituents to change course or responding to a disquiet already felt at the grassroots. But they rarely make a change without expectations of at least a chance of electoral victory.

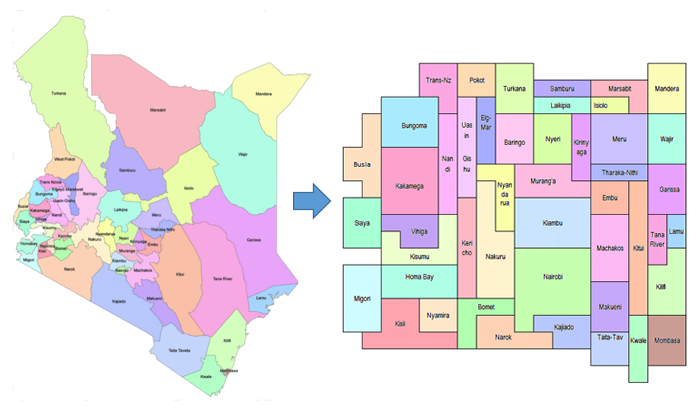

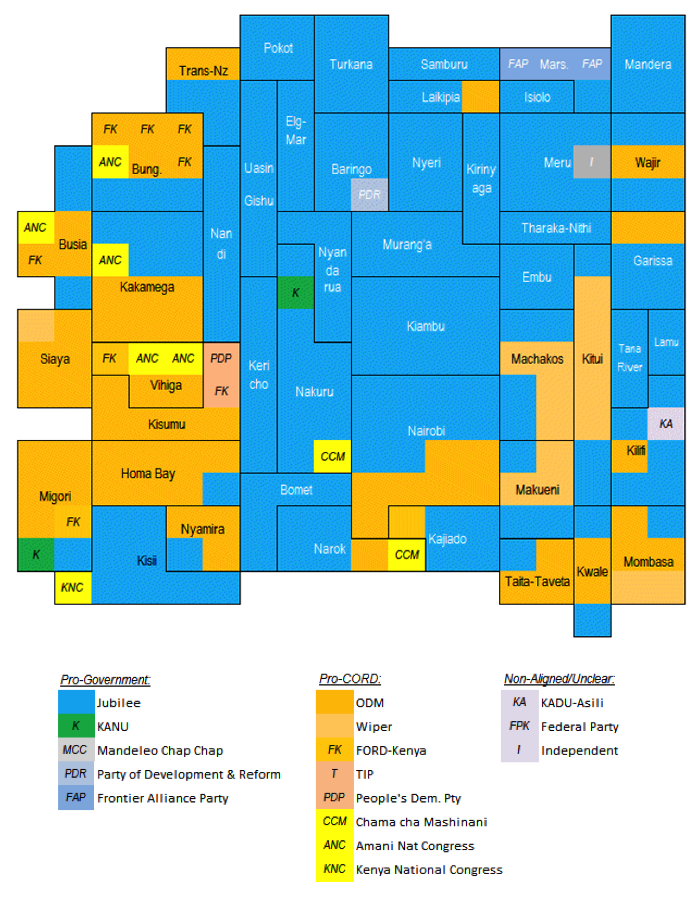

The attached images show where the 290 elected constituency MPs stood at the beginning of the party primaries, viewed by county, and each sized according to the number of seats in that county.

This is a new view of Kenya by constituency, organised according to the 47 counties. One square is one parliamentary constituency, whatever its geographical size or population. Rough geographical similarity is preserved, but it is only rough.

Opinion polls show the gap between the alliances narrowing, but Jubilee is still ahead. The end-May Ipsos poll after Odinga and Musyoka were declared as the presidential candidates showed a 47%-42% lead for Jubilee, but with 10% of those polled undecided or unwilling to answer. With so many successful or near-successful insurgent political campaigns over the last 18 months (Brexit, Trump, Macron, Le Pen, and most recently, Corbyn) nothing is certain. But most of those undecided/unwilling voters will go with one or the other alliance in the end. If simplistically, one split the “undecided/unwilling” down the middle, the result from this poll would be a 52-47 victory for Jubilee. In practice, the undecideds will probably fall – if lessons can be learned from other recent elections – slightly in favour of the more conservative option (here, the incumbent). No poll at any point has yet suggested a NASA victory.

Although a mess, the April-May 2017 party primaries were probably better run than ever before, despite the ensuing complaints, cancellations and court cases. Apart from rotating and refreshing ethno-regional political elites, however, they changed little at the national level. Party-hopping after losing has been banned, but it has been replaced this time round by a plethora of newly-independent candidates. However, these politicians are not truly independent; they are simply allies of one national faction or other who were unsuccessful in the primaries. Virtually none have changed their underlying allegiance. With so many independents, the main parties do risk splitting their vote in some marginal seats. Both alliances have this problem, though Jubilee’s is more severe. But NASA has an even more serious difficulty – their Wiper, ODM and ANC candidates are standing against each other without any pre-election deal in many parliamentary, senate and gubernatorial seats, including in Kakamega, Vihiga, Kisii, Mombasa and Taita-Taveta counties. If some cannot be persuaded to stand down, they will split their votes and may allow Jubilee candidates to slip through. This is only a problem at lower levels in the political structure though. Although eight presidential candidates have been cleared, the national race is effectively a two-horse one and a second round is very unlikely (in contrast to 2013, when Mudavadi was running as a third force and the runoff chance was much higher).

Party-hopping after losing has been banned, but it has been replaced this time round by a plethora of newly-independent candidates. However, these politicians are not truly independent; they are simply allies of one national faction or other who were unsuccessful in the primaries, and virtually none have changed their underlying allegiance.

Next, democracy is a numbers game. The “tyranny of numbers”, has become a curious point of contention in Kenya over the last decade. But much depends on how you present the concept. The “tyranny of numbers” is also “one man, one vote”: electoral democracy where all are equal and no-one’s vote is more important than any other’s. As long as that widely supported and widely praised system is in use in Kenya, victory comes with winning the support of most voting adults, not of most clans, ethnic groups or counties. So, to understand where Kenya stands, we need to look at two key numbers: the number of registered voters in each county and their propensity to turn out for their favoured candidates, and to combine these with a model of voting preference amongst the people in those counties. And, like it or not, the majority of Kenyans (probably two-thirds) can have their political alliances predicted with a high degree of confidence based on their ethnicity. This heuristic can be confirmed (or challenged) by examining where key politicians are standing in each community, the number of voters turning out in the various party primaries, fighting and complaints of intimidation by weaker parties, and whether the other “side” can even find a candidate willing to risk standing for them in some seats.

We now have provisional and unaudited registration results from February 2017 which show that 3.5 million voters were added in the last three months, with the growth fastest in the Coast and North-Eastern regions and in Nairobi. There are no obvious signs so far of structural pro-government bias in the allocation of voter registration kits or in these unaudited results. These numbers give us a strong (though unvalidated) baseline to work predictively. Next, we need to estimate the turnout figures in each county. 2013’s numbers are a solid basis for this, though turnouts will probably be a little lower across the board this time than last. Some of the turnouts last time (such as in Mandera) were very suspect and this analysis assumes – for now – that these exceptions return to the norm.

Finally, we need to make a judgement about how each county and each community within that county is likely to vote, based on previous experience, but adjusted for events and changing alliances since 2013, and the influence of major regional political figures. So, let us run through the old provinces or regions and the 47 counties one by one, to set the basis for that prediction.

Since 2016, the generally pro-CORD/ODM Mijikenda coast (Kilifi, Kwale and parts of Mombasa) has once more solidified for NASA. Many of the MPs who defected with pomp and pride to Jubilee in 2016 now look very vulnerable and Jubilee’s inroads in 2016 seem to have been reversed. Despite misgivings about the regional dominance of the controversial Hassan Joho and the Arab/Swahili community, NASA will win almost all the Coast, except Tana River, Lamu and perhaps one seat in Taita Taveta. In Nyanza, Odinga will get virtually every Luo vote, his support as solid as ever, and a plurality (perhaps 70%) of Gusii votes, where again the 2016 defectors to Jubilee look to be falling en masse.

Western Province now seems solidly for NASA too. But the result nationwide will hinge on how well Mudavadi, Moses Wetangula and others can turn out the Luhya for NASA (with no “horse in the race” now and relatively low registration in Mudavadi’s home Vihiga). Through ex-New FORD-Kenya recruits, Jubilee still has a position of sorts among the Bukusu of Bungoma and Trans-Nzoia. But I suspect Jubilee is going to poll no more than 10-15% of the vote in Western overall, even including their majority support amongst the Iteso of Busia and Kalenjin of Mount Elgon.

In contrast, Nairobi seems to be firming up narrowly for Jubilee, especially in the governorship, where Mike Sonko’s spectacular campaign is overwhelming ODM incumbent Evans Kidero’s low profile and modest legacy. A 50-50 split looks plausible at the moment, though this may change. This assumes that pro-Jubilee independent Peter Kenneth will not materially split the Jubilee vote or create a cross-party movement and that the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) does not disbar Sonko or Kidero or both.

As in 2013, Central Province will vote entirely for Jubilee. NASA has no candidates and no prospect of support here, the homeland of the Kikuyu community that is still numerically the largest in the country. Apart from the ethnically mixed peri-urban areas of southern Kiambu, more than 95% of voters in the province will back “their President”.

Despite misgivings about the regional dominance of the controversial Hassan Joho and the Arab/Swahili community, NASA will win almost all the Coast, except Tana River, Lamu and perhaps one seat in Taita Taveta. In Nyanza, Odinga will get virtually every Luo vote, his support as solid as ever, and a plurality (perhaps 70%) of Gusii votes, where again the 2016 defectors to Jubilee look to be falling en masse. The Somali North-East, in contrast, is stronger for the ruling Jubilee party than in 2013. Mandera was already wholly Jubilee in 2013 and remains so, and Wajir has been moving steadily towards Jubilee during Kenyatta’s term.

Jubilee will also win almost all the Kalenjin voters in the Rift Valley, bar the Kipsigis of Kericho, Bomet, western Nakuru and northern Narok. The alliance between Ruto and Kenyatta remains deep and strong. Despite doubts about whether the Kikuyu will really hand over the presidency to William Ruto in 2022, regional support for “their man” and for the power-sharing deal remains firm. The support for maverick Kipsigis Governor Isaac Ruto is the key variable here. With strong support in Bomet, he has the potential to fracture the southern Kalenjin vote and bring a material chunk to NASA. But I suspect that many of his supporters will vote for him for governor and Uhuru and Ruto for the presidency. Trans-Nzoia will split but probably favour NASA, Laikipia will favour Jubilee, while Nakuru will be a solid Jubilee zone.

The Somali North-East, in contrast, is stronger for the ruling alliance than in 2013. Mandera was already wholly Jubilee in 2013 and remains so, and Wajir has been moving steadily towards Jubilee during Kenyatta’s term. The incumbents have worked hard among the Somali and now only Garissa remains a battleground. The mostly pastoralist non-Somali northerners (the Samburu, Turkana, Borana, Gabbra, Rendille, Orma, Burji and Wardei) of the Rift, North of Eastern and Tana River will vote mostly Jubilee or allied parties. However there will be a few constituencies where those alliances reverse and Samburu and Turkana might still vote ODM. Among the southern communities, the Kuria will remain Jubilee, but the larger and politically significant Maasai will again split their affections. With Jubilee having made several missteps and put forward a lacklustre set of candidates, NASA will do better here than in 2013, and will probably win Narok, while Kajiado might go NASA at governor level but Uhuru for president.

In the southern half of the old Eastern province, the densely populated Embu and Meru are solidly for Jubilee (despite Odinga’s efforts) and will vote more than 90% for Kenyatta and Ruto. The key question in Eastern is how well NASA will do in Ukambani. It will win a majority in all three counties, to be sure, but their support appears weaker than in 2013. Then, Musyoka delivered 85% of the vote in Ukambani for Raila, with a turnout of 84%, not a census vote but a strong performance. Now, however, he is struggling, even after his selection as NASA’s vice presidential candidate. He has lost nearly half of his Ukambani MPs (10 out of 23) who have gradually defected to Jubilee, while recent internal disputes within Wiper and his estrangement with two of his most senior and experienced allies (Machakos Senator Johnstone Muthama and Kitui Governor David Musila) leaves him vulnerable. He also faces an insurgency of unknown power in Machakos led by influential Governor Alfred Mutua, whose “Maendeleo Chap Chap” party is allied with Jubilee. I suspect, based on current knowledge, that Jubilee will poll 20-30% of the Kamba vote.

Jubilee will also win almost all the Kalenjin voters in the Rift Valley, bar the Kipsigis of Kericho, Bomet, western Nakuru and northern Narok. The alliance between Ruto and Kenyatta remains deep and strong, and despite doubts about whether the Kikuyu will really hand over the presidency to William Ruto in 2022, support for “their man” and for the power-sharing deal remains firm.

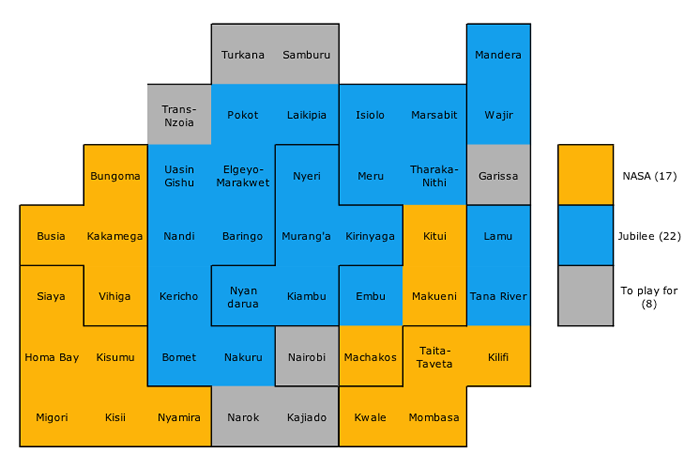

Applying this analysis at the county level gives us the following prediction for winning candidates at the presidential and county levels: 17 counties are solid for NASA, 22 for Jubilee and eight are still – in my view – in play.

June 2017 predictions of winning presidential and gubernatorial candidates

*In this image, one square is one county, whatever its size or population.

*In this image, one square is one county, whatever its size or population.

While the presidency remains the most coveted job, experience since 2013 has shown that governorships are extremely lucrative and politically rewarding roles, with MPs coming third, senators and the reserved seats for women in the house next, and county assembly members (MCAs) last (even though county assembly members are the closest to the grassroots and most likely to be known personally to voters).

As in 2013, all six contests will tend to follow a similar pattern, with most (though not all) voters voting the same way for the presidency, senator, governor and women’s representative, with more variability at parliamentary and MCA levels. I predict that Jubilee will win 23-26 governorships and NASA 21-24. The symbolically important Senate – created in the 2010 Constitution to enshrine a US-style division of legislative powers – has proved of limited effectiveness, and is likely to be abolished in the next Parliament (as its predecessor was in 1966-7).

The heavy legacy of “Chickengate” makes the IEBC extremely vulnerable to campaigns by NASA (or indeed by Jubilee, if needed) alleging its systematic incompetence and corruption, and therefore bias. That has not started yet in earnest, but the groundwork is being laid to undermine the credibility of the commission by election day, if NASA believes it will lose and that Jubilee will cheat to win.

Nationally, the combination of registration numbers, turnout and an ethnically and historically voting-based preference model still predicts a first round win for Uhuru and Ruto, by 53% to 46% (with a maximum of 1% of votes to other candidates). It suggests Kenyatta and Ruto will get roughly 8.5 million votes (of which more than 5 million will come from the Kalenjin and Kikuyu communities) while Odinga and Musyoka will poll 7.5 million, of which approximately 3 million will come from Luo and Kamba voters. This would be on a national turnout of 83%, with a regional variation from 90% in Central and Luo Nyanza to 65% in Mombasa, Kilifi and Kwale. Turnout is one of the great imponderables, however, and elections can be won or lost on the day based on successes or failures at the grassroots level in turning out supporters. Historically, Jubilee and its predecessor alliances have been slightly better than NASA and its predecessors at this, but in this election, Jubilee may have less of an advantage here.

Finally, let us turn to the referee and organiser of the upcoming contest, the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC). The IEBC, after an appalling 2016, seems to have stabilised under its new lower-profile leadership. It appears to be trying to keep its head down and focus on technical delivery of its mandate, while trying to cope with a stream of complaints and allegations of bias. It has had good success in ending party hopping, but it has so far failed to exercise its authority over the integrity issues raised about a number of high profile candidates, and has not yet responded to evidence of salaried civil servants campaigning for Jubilee. In fact, it is struggling to match its duties and obligations to the timelines allocated and seems unable to proceed whilst following competitive procurement procedures, with its every decision contested in the courts. The heavy legacy of “Chickengate” makes the IEBC extremely vulnerable to campaigns by NASA (or indeed by Jubilee, if needed) alleging its systematic incompetence and corruption, and therefore bias. That has not started yet in earnest, but the groundwork is being laid to undermine the credibility of the commission by election day, if NASA believes it will lose and that Jubilee will cheat to win.

Will there be post-election violence? Personally, I believe the experience of 2007-8 was so appalling and salutary for Kenyans that any trouble will be localised, unless the electoral abuses are gross.

Whether Jubilee could and would in fact cheat to win if necessary – in a way the IEBC could either not prevent or in which it was complicit – is a hypothetical question with strong judgemental implications. Both sides cheated last time, to varying degrees (local stuffing, forced voting and voting dead voters in their homelands). There is a strong suspicion that Kenyatta’s presidential numbers were topped up at some point in the counting process to push him over the 50%+1 threshold, which probably didn’t change the final result but finished it on the first round rather than in a runoff. The recent court case (strongly backed by NASA) to ensure that the results announced by constituency returning officers are final and cannot be corrected at the IEBC-controlled national tallying centre, even if obviously arithmetically incorrect, is designed to address this most contentious part of the whole election: the critical and semi-opaque presidential count at the national tallying centre. But whatever the outcome of that case, the presidential count will be a key flashpoint after polling day.

The recent focus on electronic transmission of the results – which so spectacularly failed in 2013 – as safer and more reliable than stamped and attested paper forms, is a potentially dangerous misunderstanding. In truth, the speed, independence and impartiality of an electronic system relies entirely on the competence, neutrality and independence of the small number of technical staff managing the IEBC’s databases and servers (who could be personally subjected to very strong pressures to “lose” passwords or make adjustments themselves to numbers) and on the ability of those teams to protect their IT systems from external hacking attempts, which the IEBC now admits happened in 2013. In fact, subtle manipulation is easier to carry out and much harder to spot electronically than with paper forms.

Will NASA and its leadership cry foul if they lose or if they think they are losing? Yes, of course they will, as they and their predecessors did in 2007 (with good reason) and 2013 (less certainly). Whether there will be any basis for this is, of course, unknowable in advance, but what is clear from 2013 is that the presidential election petition rules are so restrictive and time-bound that a successful presidential petition remains extremely unlikely under those rules. Will there be post-election violence? Personally, I believe the experience of 2007-8 was so appalling and salutary for Kenyans that any trouble will be localised, unless the electoral abuses are gross. But that still depends on how things work out over the next eight weeks. And some observers are predicting more serious trouble in specific counties.

But whatever the final outcome, it is clear that Kenya remains polarised and dangerously divided, almost down the middle, and that there is little trust or goodwill between the two major parties to work with each other in whatever political settlement that will follow the August elections.

So, the champion’s and the challenger’s players are on the pitch, the game is under way and the substitute referee’s whistle has blown. Inevitably, things will change and these predictions will need updating. I hope to do that periodically during the campaign and to “call” the result on election night. On 3 March 2013, I predicted a 50% vote for Uhuru, 42% for Odinga, with all others getting 8%. Excluding spoilt ballots, the actuals were 50.5% Kenyatta, 43.8% Odinga and 6% for the others. I’m unlikely to get it so close again.

But whatever the final outcome, it is clear that Kenya remains polarised and dangerously divided, almost down the middle, and that there is little trust or goodwill between the two major parties to work with each other in whatever political settlement follows the August elections.

Editors Comment: This article was written on the 16th of June 2017

Charles Hornsby is the author of Kenya: A History since Independence.

He lives in Ireland.