On February 9, 2014 Evelyn Anite, a former journalist and then a youth Member of Parliament for Northern Uganda, took to her knees and asked the National Resistance Movement (NRM) caucus to pass a resolution ring fencing the party chairmanship— and subsequent candidature for President— for Mr Yoweri Kaguta Museveni.

Word had gone round that Mr John Patrick Amama Mbabazi, Mr Museveni’s long-time political ally and then Prime minister, the party’s Secretary General and Museveni’s de facto number two, had had a strange dream that time had come for him to lead the Party and had therefore hatched a plan to contest against the septuagenarian leader for the Party Chairmanship and win a slot on the national ballot paper as the NRM Flag bearer.

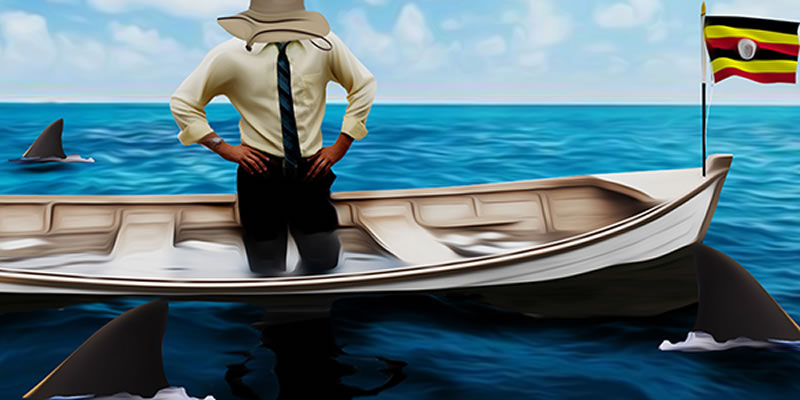

Being a Machiavellian politician and inherently scared of internal competition Mr Museveni chose to pull a fast one and chose to use a youthful legislator to crash the political intentions of his long time comrade. In using her, he also intended to send a message that the revolution, as he is fond of calling his leadership, is now in the hands of the young people.

“I welcomed the Kyankwanzi resolution in the context of party cohesion because of rumours that there were `wanters’ and ‘wanters’ who were conducting themselves in a bad way and also using subversive ways,” Mr Museveni said after winning the Party ticket unopposed.

It immediately became sacrilegious to be associated with Mr Amama Mbabazi. Although he went ahead and contested for President as an independent, he became a political outcast in the party. For her work, Ms Anite was awarded a ministerial position as State Minister for Youth first and now for investment.

How the ring fencing quashed Political hope

Although Mr Mbabazi was not a trusted politician per se— because of his long relationship with Mr Museveni and his fingerprints being all over the repressive legislations and policies in the country—the opposition, weak and divided, had hoped that a challenge from within NRM would be chance at weakening, and probably putting an end to Museveni’s three decade rule. Or at least it would divide a Party so entrenched that there’s a thin line between it and the state.

Being a Machiavellian politician and inherently scared of internal competition Mr Museveni chose to pull a fast one and chose to use a youthful legislator to crash the political intentions of his long time comrade.

Ms Anite’s motion therefore, ensured the maintenance of the political status quo in the lead up to the 2016 General elections: an incumbent with priestly control over the Party and an opposition without any new force other than the usual FDC’s Dr Kizza Besigye.

With the contest for the presidency poised to be with the usual candidates especially after proposals for political reforms before elections were rejected by the majority ruling [party?], in particular the creation of an independent electoral commission, hope for political change was quashed even before the elections.

Just after President Museveni was announced winner, with 5,617,503 votes, or 60.7 per cent, the opposition and the majority youth who had lined up in droves to vote rejected the result.

The voting had been conducted with its fair share of controversies: blocked social media platforms, delayed voting material in most parts of the country like Kampala and Wakiso which had the highest number of voters believed to be opposition.

The opposition declined an invite to the presidential swearing in ceremony. Calls for an international audit of the votes fell on deaf ears. Mr Mbabazi’s election Petition had just been defeated in the Supreme Court and so the ruling party felt they had cemented the win and there was no need for further scrutiny. Frustrated, the youth formed a social media brigade and declared Kizza Besigye, who got 3,270,290 votes (35.37 per cent of the ten million voters that cast ballots) the people’s president. As a nod, the FDC leadership videotaped a mock swearing in ceremony of the ‘people’s president’ and supplied it across social media platforms.

A politically rudderless youth leadership

Shout and quarrelling on social media is seemingly what the youth can do.

Sometime time back in the ninth Parliament, this writer had short conversation with then Health Minister, now Prime Minister Ruhakana Rugunda, on what the former UPC youth winger and President Milton Obote’s protégé thought about the political situation in the country.

Straight up, Ndugu Rugunda, as he is fondly called, responded: “When I was a young man like you, I was politically active. I rose up and spoke against what was wrong with government and we ensured that things changed. Do you expect me to speak against a government I worked to bring in power?”

Unlike in the sixties when then young men like Premier Rugunda benefited from vibrant and powerful students’ associations like the Uganda National Students Association and powerful political party youth leagues, today’s politically aware youth has been denied a platform for political expression—barazas were banned but students associations, especially at universities, which used to be the centers for free political discourse, have largely been monetized.

It used to be lucrative to be an opposition Guild President at Makerere University for one would use the platform to speak to power and push the political youth agenda. Now, it is lucrative because one can easily be identified and taken into NRM fold to eat. Ms Suzan Abbo, who was a vocal Democratic Party member while Makerere University Guild President, crossed to work in State House immediately after graduation.

Ms Anite’s motion therefore, ensured the maintenance of the political status quo in the lead up to the 2016 General elections: an incumbent with priestly control over the Party

Political party Youth Leagues are dead. They hardly issue a statement on the political on goings in the country but become active toward General elections to offer their support for sale to the highest bidder. It is in that period that you see groups like the poor youth coming up demanding money for youth projects then disappear after the elections.

Most of the leaders work to tow their party leaders’ line in anticipation of favours. Once, this writer challenged the then NRM Youth League Secretary General, Robert Rutaro (a former Makerere University Guild President) on why the NRM youth league was not as vibrant as that of South Africa’s ruling African National Congress’ youth league under Julius Malema. His response was to blame poor funding from the party leadership; for a team of young leaders who are not in gainful employment, the focus was on convincing the party chairman to get them jobs.

Little wonder that whenever youth leaders [meet?] from across the country, the fights that are reported in the media are not about ideas but transport refund.

With more than 60 per cent of the population being youth, the lack of a strong youth leadership means that the young people may not have a strong say in the big political transition question, unless their youth representatives in Parliament choose to step forward.

A shot at an inclusive government and a weak opposition

After being sworn in, President Museveni appointed over 80 ministers, among them his wife Janet Kataha Museveni, whom he gave the education docket. He also however, appointed army officers, like former Commanders, Katumba Wamala and Abubaker Jeje Odongo to head works and internal affairs respectively.

A retired army general himself, President Museveni believes in deploying soldiers to do assignments he wants to impact people. He, for instance, disbanded National Agriculture Advisory Services (Naads) a lead agriculture project and renamed it Operation Wealth Creation to supply seedlings and supervise agriculture development. It is now being implemented by soldiers under the leadership of his brother Caleb Akandwanaho, also a retired army general.

However, as if to calm the political pressures and public resentment of an election exercise some saw as unfair and influenced, Mr Museveni, when constituting his government, also appointed individuals from the opposition into ministerial positions and others were appointed by the Government Chief Whip to sit on Parliament committees.

Uganda People’s Congress’ Ms Betty Amongi, wife to UPC’s contested president, James Akena (himself a son to Uganda’s first President and UPC founder, the late Apollo Milton Obote), was given the influential Lands Housing & Urban Development Ministry.

Former FDC member and one time presidential candidate under the little known Uganda Federal Alliance, Betty Kamya, was given the Kampala City Council docket.

Democratic Party’s Florence Nakiwala Kiyingi was given State Minister for Youth and Children Affairs.

In Parliament, FDC’s Beatrice Anywar was announced, by the Government (and NRM’s Chief Whip) as vice Chairperson of the House committee on Gender, Labour and Social Development.

After being declared winner of the 2016 elections, Mr Museveni announced from his Rwakitura country home and announced that he will “wipe out the opposition completely in the next five years”.

Although there are several registered political parties, there are only three pronounced opposition political parties in Uganda: The Uganda People’s Congress (founded in 1960 and party to the country’s founding father the late Apollo Milton Obote), the Democratic Party (the oldest party in Uganda founded in 1954) and the Forum for Democratic Change, the home of Mr Museveni’s main challenger, Kizza Besigye.

Apart from the FDC which, thanks to Dr Besigye, manages to keep itself in the news with anti-establishment rallies and is therefore a darling to many youth especially in the city and townships around the country, UPC and DP are shadows of their former selves: dogged in internal political bickering.

In UPC, the Party President, James Akena is accused of trading his father’s party to President Museveni in return for political favours. Many in the party see the appointment of his wife as one such favour. Prior to the 2016 General Elections, Mr Akena announced a “party decision” to work with President. By that time, he had already been branded an NRM mole by a UPC faction led by Joseph Bbosa, a long time UPC member, who accused Mr Akena of having received UShs1 billion to hand over the party to Mr Museveni.

The opposition is weak and uninspiring to the young—many of its former Young Turks and high ranking cadres like former DP’s vice chairman, Mohammad Kezaala have openly looked for financial help from the President Museveni and willingly crossed the political line to be appointed deputy ambassadors without a substantive station.

In the Democratic Party, the president, Nobert Mao has also faced opposition from within, with many accusing him of being Mr Museveni’s project. The Lord Mayor, Erias Lukwago, a strong DP member, for instance shows more loyalty to FDC’s Besigye than to his party President.

The opposition is weak and uninspiring to the young—many of its former Young Turks and high ranking cadres like former DP’s vice chairman, Mohammad Kezaala have openly looked for financial help from the President Museveni and willingly crossed the political line to be appointed deputy ambassadors without a substantive station.

The passing of the Public order management bill has continuously made it difficult for the opposition to mobilize or even sit under a tree in a group without the permission of the police chief. Many in the opposition, therefore, have resorted to being vocal at funerals and those who are more daring try to organize rallies around the city but those are usually easily dispersed by a ruthless, usually trigger-happy, anti-riot police.

Therefore, President Museveni’s appointment of opposition members in his cabinet, Dr Frederick Kisekka-Ntale, a Kampala based political scientist, argues is not a move to create an all-inclusive government but a move to weaken the opposition more and keep himself in power.

The age limit question

In 2005, when he wanted to prolong his stay in power, President Museveni, just as he was to do with Ms Anite twelve years later, picked a then less known Kabula County representative, James Kakooza, to move a motion in Parliament for the removal of term limits. In what was popularized as Kisanja (term limit) project, Members of Parliament were each given shs5 million to “facilitate” their decision making.

Article 102 (b) of the 1995 constitution of the Republic of Uganda, as then amended, says that “A person is not qualified for election as President unless that person is not less than Thirty five years and not more than seventy five years of age.” Now 71 years old, this should ideally be president Museveni’s last term. However, there is already a popular push among NRM legislators to have the constitution amended to remove the age limit clause. That will essentially mean that without term and age limits, president Museveni could stay in power until the grim reaper decides.

“No one can replace Afande Museveni. He has been our leader from during the war and he has to continue leading us until he dies. The constitution was made by men and we can change it any tine we want,” Mr Ibrahim Abiriga, the Arua Municipality member of Parliament told this writer in a recent interview at Parliament. Mr Abiriga, a retired soldier, dresses in all yellow, the NRM party colour seven days a week—he even drives a yellow beetle Volkswagen. He says he would jump on the earliest opportunity to move the motion to remove term limits.

All through the years, President Museveni has always said that the decision to remain in power is not for him to make but for the people through their representatives, the MPs. About the age limit debate, he said in March that he is only concerned about the future of Africa but not “small things like age limit”. This was weeks after his son-in-law, Odrek Rwabogo, wrote a missive calling upon the country to start debating issues of political transition, economic reforms and internal democracy in the ruling party.

President Museveni has a penchant for distancing himself from projects that make him look like he wants to stay in power. He likes the I’m-here-because-you-asked-me-to-and-it’s-for-your-own-good line. However, word in the corridors of Parliament is that he has already given deputy Attorney General, Mwesigwa Rukutana the nod to lead the constitution review team that will eventually deliver an age limit free constitution.

“No one can replace Afande Museveni. He has been our leader from during the war and he has to continue leading us until he dies. The constitution was made by men and we can change it any tine we want,” Mr Ibrahim Abiriga, the Arua Municipality member of Parliament told this writer in a recent interview at Parliament.

Coming from the Western part of the country like the President, Mr Rukutana is one of his trusted lieutenants. He has served in cabinet for over 10 years and was part of the legal team that represented him in the Mbabazi Presidential election petition. With a largely NRM dominated Parliament (298 out of the 388 directly seats), the biggest fear by those opposed to the removal of age limits is that the ruling party could easily use the tyranny of numbers to have their way. A number of ruling party legislators this writer has spoken to however say they would have to be paid by Mr Museveni to allow the removal of the age caveat.

An insecure worried population

One mid-morning early this year, Andrew Felix Kaweesi, the Assistant Inspector General of Police and the force’s spokesperson was assassinated by unknown gunmen. It was in a similar way that several other Ugandans had been killed. Two people show up on a bike, shoot at the target and ride off.

Suspects are usually arrested, tortured to confess but none is yet to be placed at any scene of crime.

Hit men continue to kill people and general robbery is on the increase across the country, yet the President has continued to renew the Inspector General of Police, Gen Kale Kayihura’s contract. He has served since 2005.

In the wake of the much publicised police torture of Kaweesi’s murder suspects, the police leadership has continued to give contradicting statements referring to the visibly deep wounds on the suspects as “mild”

Instead of working together to address the security situation and reform the police, Gen Kayihura and cabinet Minister for security, General Henry Tumukunde, are instead engaged in endless catfights, each accusing the other of incompetence.

It is allegedly said that the genesis of this conflict is over the security budget, who should own it and decide on its expenditure. President Museveni feeds off the bickering. He usually sets different agencies against each other by separately asking them to do the same job and have them try to outcompete each other as they fight to win his favour.

In the country side the population is suffering with issues like prolonged drought, army worm and nodding disease in the north; with increasing market prices for house hold necessities like sugar and food stuff. The common man has increasing become apprehensive and worried about the future. The only hope sometimes lies in Parliament where on almost a weekly basis, speaker Rebecca Kadaga is petitioned at least thrice on issues ranging from a deroofed school in a village far away from Kampala to issues like torture in police cells.

The Speaker has always been responsive, using her seat to give directives to government officials and ministers to put things right.

Sometimes she has succeeded, like in when she ordered for an extension of the phone sim card registration deadline to allow for time for people up country to register, sometimes she simply gets winding stories and excuses from government like in the case of torture of people in police cells.