Nairobi, Kenya – A WATER GLASS SHARED BY 200 ADDICTS

In downtown Mombasa, a nondescript office sandwiched between multistoreyed buildings is busy as usual.

Every five minutes or so, gaunt youths, eyes bloodshot, walk into the tiny reception and straight away dash to the water dispenser at the far corner. They refill the only plastic glass next to the dispenser without rinsing it, and eagerly empty its contents before turning to the reception desk.

Between 9.30 am and 10.30 am, as this writer waits for the director of Reach Out Centre Trust, an independent outfit that helps Mombasa residents fight drug addiction, the 10-litre dispenser bottle is already finished, but it is instantly replenished. The office doesn’t seem to have a designated receptionist. But the hushed talk between the visiting youths and any official around the reception ends up in a familiar refrain.

‘Sorry, the methadone [an analgesic drug similar to morphine used in the treatment of heroin addiction] hasn’t arrived yet. We were promised a new batch a fortnight ago but nothing is here yet. But please, do keep checking.’ Then the dejected youths – one in five are female – leave the building. The ‘clients’ (known by the derogatory term mateja), are hooked on madawa, the local phrase for heroin and/or cocaine.

NACADA says 0.1% of Kenyans consume heroin; implicitly, Kenya is a trafficking rather than a consumer country although reports indicate that it is increasingly becoming an end-user

They want to break the habit, and methadone is the only solution they know about. But it has been in short supply lately. Donors had delayed disbursing funds for the acquisition of methadone. Nonetheless, the water appears to cool their nerves – for the time being. By the close of the day, more than 200 clients will have shared the glass, many of them without rinsing it.

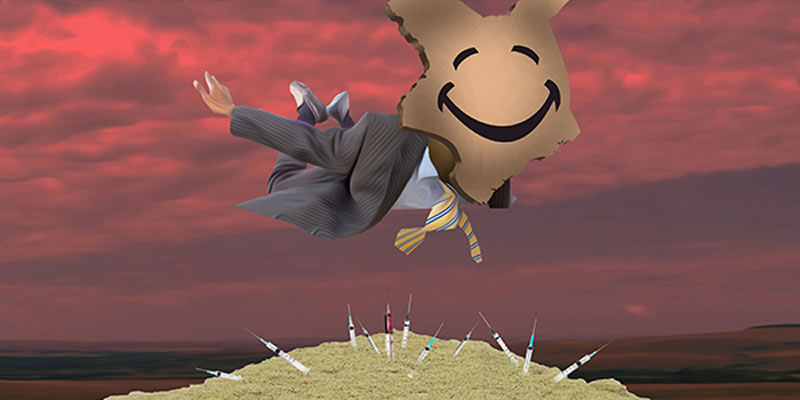

Ominously, the casual way they use unwashed glasses (and thereby risk contracting hepatitis B), is the way they share heroin needles – a sure way of transmitting HIV. And as will be seen later in this report, injectable drug users (IDUs) have become the key agents of HIV spread in the country, accounting for about 18 per cent of new infections.

There are dozens of such methadone clinics, first introduced last year at Kenya’s Coast. Nairobi’s Mathare Hospital started administering this medication in 2014; its specialised clinic treats 450 patients daily. The 51 beds in the rehab ward are always full, with each patient staying 90 days. At the Coast, the Malindi and Mombasa government hospitals each treat 200 addicts a day.

The government moved to introduce methadone following the death of addicts triggered by heroin shortages occasioned by clampdowns on drug barons. Over 100 addicts died in 2011, many more in 2013-2014, though the total number is yet unknown.

According to the International Drugs Policy Consortium (IDPC), heroin started to be consumed in Kenya in the cities that were used as transit points (such as Mombasa) before spreading to other regions of the country and to Nairobi. Now, some 20,000 to 55,000 Kenyans inject heroin. The National Campaign Against Drug Abuse (NACADA) says it is monitoring 25,000 intravenous drug users (IDUs) spread around the country. The population that snorts the drug is still unknown but it could be larger than that of IDUs, according to the Anti-Narcotics Unit (ANU) officials.

These addicts are part of the $322 billion global drug market, as valued in 2011. And as will be seen later in this article, East Africa, a key transit hub for drugs destined for Europe and the United States, contributes $10 billion to this business. Kenya is a major player, as a trafficking hub, in this illicit global commerce.

NACADA says 0.1% of Kenyans consume heroin; implicitly, Kenya is a trafficking rather than a consumer country although reports indicate that it is increasingly becoming an end-user. ‘While data on heroin users in Kenya is limited, UNODC (UN Office on Drugs and Crime) has warned that heroin addiction appears to be on the rise in the country, particularly along the Coast,’ American online news portal huffingtonpost.com said a year ago.

‘Only a tiny fraction of the drugs believed to transit in and through Kenya is seized by authorities. Arrests rarely lead to convictions. When convictions occur in Kenya, they are of lower level couriers and distributors’

The heroin comes from Afghanistan and gets here via Pakistan. According to experts, things look bad this season. Afghanistan’s opium production could reach a new high – about 8,800 tonnes (which can produce as much as 530 tonnes of heroin). Volumes have been on an upward trend since 2010, and reached a record high in 2014, says the UNODC. Eight per cent of this will pass through the East African region, what the UNODC calls ROEA (Region of Eastern Africa that draws in Kenya, Tanzania, Burundi, Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Rwanda, Seychelles, Somalia, Sudan, Uganda).

Given that 12 per cent of that is consumed locally, 5 tonnes (with an estimated street value of $1.3 billion) will remain in the region, with Kenya being the major consumer. But other reports indicate a higher figure. About 8 tonnes enter Kenya, according to a Reuter news article of March 2015 headlined As Heroin Trade Grows, a Sting in Kenya.

BLOOD FLASHING: A DEADLY SHARING

A year ago, huffingtonpost.com published a worrying story about Kenya’s drug problem titled Recovering Addicts Battle Kenya’s Exploding Heroin Problem. It said as more heroin flooded into East Africa, more and more Kenyans were getting hooked on it.

‘Drugs are destroying our communities,’ MP Abdulswamad Shariff Nassir has lamented. His Mvita constituency is among those hardest hit by the drugs problem in Mombasa, with other hotspots being Likoni and Kisauni. ‘The courts have to protect our citizens, and that’s not happening.’

The Mombasa ‘carnage,’ in the words of a Coast-based senior medical officer, wasn’t entirely unexpected. As early as 1998, Noah arap Too, then head of the country’s Criminal Investigation Department, the police arm charged with arresting trafficking among other crimes, sounded a warning, as did the United Nations.

Nothing happened. Michael Ranneberger, the United States ambassador who during his tour of duty from 2001-2011 made the anti-corruption war a personal crusade, much to the chagrin of the then regime of president Mwai Kibaki, wondered whether the country’s inertia in fighting narcotics was ‘Incompetency? Lack of will? Or worse?’ as reported in Wikileaks.

The sin of omission has caught up with Kenya. Today in Mombasa, addicts do what is called ‘blood flashing’ – the sharing of heroin-laced blood between those already high and those in need of a quick fix, practised by addicts who cannot afford the drug. This fatal ritual has been going on for about a year now, according to medical experts at the Coast.

Rene Berger, the USAid Kenya HIV/Aids team leader, says blood flashing is putting anti-HIV programmes in Kenya at risk, and warns that joblessness, prostitution and drug abuse are fuelling a ‘sense of desperation’ at the Coast.

Already, injection of heroin is becoming a key factor in HIV transmission. Figures are scanty as no serious research has been undertaken to link the drug to the spread of the disease, but the information available indicates that HIV prevalence among male drug users is 18 per cent while among females it is 44 per cent. (The country’s HIV prevalence is 6 per cent)

Reports indicate that long time addicts have turned to cocktails – combinations of cocaine, heroin, marijuana and the so-called designer drugs such as methamphetamine, and alcohol – to get their fix.

‘It’s clear that the Coast is an entry point, and wherever there’s a path, there are some crumbs left behind,’ Sylvie Bertrand, regional adviser for HIV/Aids at UNODC’s Eastern Africa office, told the press.

TRAFFICKING HOTSPOT: A SURGE THROUGHOUT THE REGION

Each year, the Kenya Police and the UN issue reports on the drugs situation. One of the reports is global while the other is local; one is analytical, the other primarily statistical. Notwithstanding their different styles, however, both reports portray a country that is battling with a drugs problem.

A section called ‘Dangerous Drugs’ in the Annual Crime Report by the Kenya Police details trends in arrests of drug users and traffickers. It reveals a consistent increase in cases related to drugs in the past 10 years. For instance, dangerous drugs (which is the description for heroin, cocaine and meths) recorded a 12% jump in 2014 over the previous year. That year’s report shows that there were 73 heroin cases that led to 94 arrests, and recoveries amounting to 10.5 kilos, 558 sachets, 2,000 litres of diesel mixed with heroin, and 3,200 litres of liquid heroin.

In the 2015 annual report, the incidence of dangerous drugs went up 14% over the previous year.

On the other hand, the UNODC Maritime Crime Programme in its 2014 annual report talks about an ‘alarming spike’ in illicit drug trafficking throughout the Indian Ocean Rim. It says that there has been a ‘surge in rates of drug trafficking throughout the region, particular with respect to heroin’. Another report by this UN agency, Drug Trafficking to and from Eastern Africa, paints Kenya as a country in the grip of drug cartels. It says that ‘a review of drug seizures from 1998 to date indicates an increase in the trafficking of heroin’ in Kenya.

It turned out wasn’t just cars and TVs the clearing and forwarding agencies were clearing. Heroin and cocaine were far better earners. In fact, of the 10 known local drug barons, nine own, or once owned, import and export companies in Mombasa and Nairobi

In a report published this year, the US State Department says, ‘Kenya is a significant transit country for a variety of illicit drugs, including heroin and cocaine, with an increasing domestic user population.’

Kenya’s transformation into a trafficking hub has been picking up speed in the past 10 years. In April 2014, an Australian Navy patrol seized heroin valued at $290 million (about Ksh29 billion) off Kenya’s Coast. This amount is equivalent to all heroin seized in the East African region in the two decades 1990-2009. Today, 40 tonnes of heroin are believed to be trafficked through East Africa annually, up from 22 tonnes in 2013 and four tonnes in 2009.

Alarmed by the amount of drugs coming from Kenya into the West, the US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) jointly with the Kenya police created a 16-member specialised force called the ‘Vetted Unit’ to track down drugs and drug lords. And as will be seen later in this article, this is the unit that set up and arrested the Akasha brothers (Baktash Abdalla and Ibrahim Abdalla) and their Indian cohorts in a sting operation last January.

The multibillion-dollar trafficking business has attracted international drug barons, created local cartels, and left a legion of ‘mules’ serving jail terms in foreign lands, with dozens of them on death row. The industry’s proceeds are laundered through banks, supermarkets, forex bureaus, clearing and forwarding companies, hotels and real estate, lottery and gaming companies, casinos, hospitals and high-end bars and exclusive clubs.

The statistics that do exist would place a figure on the business as being worth between $100 million and $160 million annually. But these figures are based merely on seizures, and as the US State Department Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs says, ‘Only a tiny fraction of the drugs believed to transit in and through Kenya is seized by authorities. Due to a lack of political will and institutional capacity, arrests rarely lead to convictions. When convictions occur in Kenya, they are of lower level couriers and distributors.’

The deportation of 120 suspected drug barons in 2013 is an indicator of the allure of the Kenya market for the global underworld.

NO LONGER A BLIP ON THE GLOBAL MAP

Indeed, as indicated earlier in this report, it isn’t happenstance that Kenya finds itself in this situation. As early as 1990s, Noah Arap Too, the then Criminal Investigation Department head, had warned about an impending crisis in the country. ‘It will be a hard and challenging job for law enforcement officers,’ to eradicate narcotics in Kenya, he said.

Prior to this warning, Kenya was perceived a mere blip on the global map of heroin. News reports then named countries such as Nigeria, Colombia, Pakistan and Afghanistan. In fact, in Kenya, most drug-related stories were about marijuana that was being produced locally. Only a tonne of heroin was seized off the East African coast between 1990 and 2009.

This picture turned out to be deceptive. According to later reports, cocaine and heroin were already here, having arrived during the tourism boom of the 1980s.There were red flags here and there but authorities, either out of complacency or because of corruption or both, declined to read the warning signs.

Attempts to arrest suspected barons have been hampered by the fact that many are in government or have business associates within the government

For instance, drug lord Ibrahim Akasha was at the time assembling a deadly kinship machine that would later torment the West, forcing Americans to demand the deportation of his children to answer charges of transporting drugs to the United States and Europe. The Akasha family ‘controlled drugs along Mombasa to Europe’ as early as the 1990s, according to Wikileaks cables.

Another red flag was the mushrooming of clearing and forwarding companies, ostensibly to cash in on the booming imports of second-hand cars and electronics. By 2007, at least 824 had registered with the Kenya Revenue Authority, a figure that would shoot up to 1,298 by 2014. It turned out wasn’t just cars and TVs these agencies were clearing. Heroin and cocaine were far better earners.

In fact, of the 10 known local drug barons, nine own, or once owned, import and export companies in Mombasa and Nairobi.

And when the drugs business boomed, the barons went ahead to create their own Container Freight Stations (CFSs). At the CFSs, containers are verified, cleared, unpacked and delivered to their destinations. Until recently, these stations were barely policed, and so became conduits through which drugs could be smuggled into the country with relative ease.

Kenyan authorities have thus been sleeping on the job. Apart from an anti-narcotics law – that provides for life imprisonment, Ksh1 million ($10,000) fines and seizure of ill-gotten wealth, little if any concrete action has been taken. In 2009, some 11 years after Noah arap Too’s statement, the Anti-Narcotics Unit, had just 100 officers to police the entire country. They couldn’t even track the 824 clearing and forwarding companies registered at the time.

Now, Kenya is suffering from the sins of omission. That explains why Huffingtonpost.com, views Kenya as ‘a forgotten hotspot of the international drugs trade’.

A CONSUMER REPORT FOR THE UNDERWORLD

There is an Internet portal that prides itself on being ‘a consumer report for the underworld.’ Havoscope.com publishes the global prices of drugs, as well as figures for money laundering, piracy and counterfeiting on the black market. In the latest upload, the price of heroin in Kenya was listed as $1.9 per gram, the cheapest among the 72 countries the Internet portal has surveyed. Brunei’s $1330.04 per gram is the most expensive followed by New Zealand at $717.4 per gram. In the United States, the price is $200 while in the United Kingdom it is $61.

In Africa, South Africa’s price is $35.1 per gram, Zimbabwe’s is $27.1 and Nigeria’s is $6.8.

In one of the cables it has released, whistle-blower Wikileaks confirms the local prices of heroin at between Ksh100 and Ksh200 a gram. The same cables say mules earn between $3,000 and $6,000 depending on the destination of the drugs and how easy it is to traffic them to that destination. Mules can make as many as six trips in a year.

Yet these figures, mindboggling as they are, do not tell the entire story about the Kenyan narcotics business. Heroin here is almost the purest in the world – usually above 80 per cent and ‘readily available and relatively inexpensive,’ according to the Wikileaks cables.

(Addicts wary of contracting HIV/Aids prefer pure heroin because it can be snorted through the nose as opposed to the diluted form used by IDUs).

A number of reasons explain why the drug, though pure, is cheap: Corruption (within politics, government and security agencies), ease of operation by drug lords (entry and exit from the country), geographical location of Kenya in relation to the drug’s origin and destination, a poorly secured and policed financial market, legislation that is not deterrent enough, and the high stake politics that drive the country.

i. Corruption

The Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, in its 2016 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report (INSR) says: ‘Stemming the flow of illicit drugs is a challenge for Kenyan authorities. Drug trafficking organisations take advantage of corruption within the Kenya government and business community, and proceeds from drug trafficking contribute to the corruption of Kenyan institutions. High level prosecutions or large seizures remain infrequent.’

Indeed, politics has come in the way of the work of the country’s anti-narcotics agency. ‘Politicians may be opposed to the drug barons in theory but when it comes to business, they are bed-mates,’ says an ANU officer. Attempts to arrest suspected barons have been hampered by the fact that many are in government or have business associates within the government.

Drug lords have contacts in the government, politics (governors, senators, MPs), the religion industry (evangelical preachers) and in the country’s top security agencies

The police source calls it ‘high-stakes politics’ because of the price drug lords pay to protect themselves and their trade. Almost all senior politicians, even those not directly involved in drugs, find themselves on the payroll of the narco-barons.

They have amassed considerable wealth they can use to intimidate and threaten the law and law enforcers.

Sometime back in December 2010, the then Internal Security Minister George Saitoti named in Parliament five lawmakers (Harun Mwau, William Kabogo, Hassan Joho, Simon Mbugua and Mike Mbuvi) as well as tycoon Ali Punjani and long-rumoured unofficial Kibaki second wife, Mary Wambui, all of whom he said were involved in narcotics trafficking. The unprecedented move followed pressure from the international community to have Kenya act against the vice.

A team of police officers formed to carry out investigations into the matter uncovered no evidence to charge the five. Kenya’s leading newspaper, Daily Nation, claimed succinctly that the probe had come ‘up with zero’.

The Interim Report on Drug Trafficking Investigations had said of Mwau, thus ‘No evidence has so far been found to link him with drug trafficking.’ Six months later, the US government declared Mwau a global ‘narco-kingpin’ and moved to freeze his assets. Americans estimate that he is worth $300 million.

Saitoti, who had earlier served as Kenya’s vice president, would die in a plane crash in June 2012. Several MPs, incidentally among them Mwau, claimed in Parliament that he was killed by drug syndicates although they released no evidence to corroborate their charge.

There are politicians and police who facilitate the trafficking of drugs and provide protection to the cartels, there are those who conceal the identity of the cartels, and there are those who get paid to ensure that vessels carrying drugs are not destroyed. And lastly there are those who benefit from drugs seized from traffickers. ‘The nexus is huge,’ says an anti-narcotics officer based in Mombasa.

‘Drugs barons have bought some of our officers and this is very sad… We have information that police vehicles and ambulances are being used to transport drugs within Mombasa County and the Coast region,’ Mombasa County Commissioner Nelson Marwa told journalists in December 2015.

Drug lords have contacts in the government, politics (governors, senators, MPs), the religion industry (evangelical preachers) and in the country’s top security agencies.

ii. Links

In 1998, Koli Lur Kouame, then local head of the UN control agency, described Kenya as a ‘port of call’ for traffickers. Since then, various reports have portrayed the country as a major transit hub for drugs.

Kenya has extensive air and marine links to Europe, the Americas and Asia, as well as within Africa.

According to sources, bulk heroin comes from Afghanistan through Pakistan or Iran, often concealed in consignments of sugar, rice, used motor vehicles, second-hand clothes, tea, fish and other imports. It is stuffed in bulk cargo to make it difficult for scanners to detect it at the entry points. The $290 million’s worth of heroin destroyed by Australian Navy in Mombasa in April 2014 was concealed in bags of cement.

UN officials say the coastline between Somalia and Mozambique is the major trafficking zone for heroin. Apart from the official entry points, such as Mombasa and Dar es Salaam ports, this coastline has hundreds of unregulated entry points that emerged centuries ago to facilitate the slave trade and now serve as trafficking points for drugs, humans and smuggled goods. The drugs enter directly through Kenya’s coastline or via its porous borders with Somalia and Tanzania.

The porous borders the country has with Somalia, Uganda, Ethiopia and Tanzania ‘provide low risk opportunities … for those engaged in illicit trade,’ Peter Gastrow says in his ground-breaking study, Termites at Work: A Report on Transnational Crime and State Erosionin Kenya, published in 2011.

In Kenya, the heroin is blended and repackaged as tea or coffee and chocolate to avoid detection, then transported through Jomo Kenyatta International Airport (JKIA) or shipped to West Africa, Europe and the United States. Some couriers, especially West Africans and Kenyans, ferry the drug as pellets in their tummies.

Initially, heroin made in Afghanistan entered Europe via Pakistan, Iran, Turkey and the Balkans, what is known as the Opium Trail, and the northern route via Central Asia and the Caucasus to Russia and the West.

For decades, it was the preferred route for drug networks. But in 2010, authorities in Tanga, northern Tanzania, after arresting four Tanzanians and two Iranians with 95 kilos of heroin destined for Kenya, stumbled on another route, the Smack Track or Southern Route.

The absence of a Coast Guard has made drug trafficking easy. The Navy boats on patrol cannot possibly track all the boats that ply Kenya’s 1,420-km coastline. Authorities are convinced that dhows, boats and big vessels pick up drugs on the high seas on a large scale and transport them to the mainland.

It is not certain how many boats and dhows ply the coastline but Lamu County alone, which covers 45.7 per cent of the coastline, has 4,000 registered boats. The actual number is unknown because most vessels are not registered with the Kenya Maritime Authority.

Kenya’s coastline, and Mombasa port in particular, is like a magnet for traffickers. Kilindini Harbour handles 700,000 standard size containers annually. Only 1% of the containers are inspected. Transit containers and big vessels are barely searched.

Joanna Wright in the UNODC report Transnational Organised Crime in Eastern Africa: A Threat Assessment, claims that there is ‘an awful lot (of heroin) coming in from the (Kenya) Coast’. The country is no longer ‘a backwater producer of marijuana,’ as it was regarded two decades ago.

However, reports indicate that Nairobi appears to be taking over from Mombasa as heroin distribution hub. ‘While international heroin traffic might still be heavy around the Kenyan coast, local supply chains are predominantly coordinated from Nairobi,’ says Margaret Dimova in the report, A New Agenda for Policing: Understanding the Heroin Trade in Eastern Africa.

iii. Laundering

Kenya’s 43 licensed commercial banks, dozens of microfinance institutions and mortgage finance companies, almost 100 forex bureaus, dozens of Somali-style hawallah networks, and many makeshift or unregistered/unlicensed ‘saving and lending’ organisations, are a major attraction to the underworld.

For years now, Kenya’s relatively developed financial infrastructure has been a boon to drug barons. The country’s 43 licensed commercial banks with their extensive branch networks in the region, dozens of microfinance institutions and mortgage finance companies, almost 100 forex bureaus, dozens of Somali-style hawallah networks, and many makeshift or unregistered/unlicensed ‘saving and lending’ organisations, are a major attraction to the underworld.

There are almost 130,000 money agents in Kenya, working mostly with the mobile money provider M-Pesa.

This vast infrastructure is attractive to drug lords out to conceal their earnings. They can transfer their ill-gotten wealth to their home countries, pay for the ‘goods’ or receive payments for the same, and clean up the money within Kenya by investing in the financial markets, real estate and other properties.

In fact, Kenya is among the 67 countries the US Department of State denotes as ‘money laundering countries of 2015.’ In Africa, only Kenya, Nigeria, Somalia and Zimbabwe appear in the classification of ‘jurisdictions of primary concern,’ according to its publication, International Narcotics Control Strategy Report 2016. It states, ‘Kenya remains vulnerable to money laundering and financial fraud. It is the financial hub of East Africa, and its banking and financial sectors are growing in sophistication. Furthermore, Kenya is at the forefront of mobile banking.’

It is for this reason that the Financing Reporting Centre (FRC) was established in 2012 to track such illicit proceeds. However, because of the lack of capacity, the FRC has only managed to process 254 of the 878 suspicious transaction reports (STRs) submitted to it since it was created, and forwarded the results to investigation and prosecution agencies. Nobody has been convicted.

iv. Legislation

The Narcotics Drug and Psychotropic Substances (Control) Act came into force in 1994. It provided for a Ksh1 million ($10,000) fine and seizure of wealth. At the time, this was regarded as highly punitive and deterrent enough. But as it turned out, the legislation has hardly proved a deterrent.

Indeed, in hindsight, this piece of legislation may be a blessing in disguise for cartels.

Firstly, the drafters lacked foresight; the legislation appears to target marijuana and not necessarily hard drugs such as cocaine, heroin and the designer drugs. If you look at the penalties, in particular the fine, it is clear that authorities didn’t foresee a much higher-value drug. Heroin, cocaine and the so-called designer drugs are pricey. An offender needs just a half kilo of heroin to pay the fine.

In a report published after Kenya’s 2013 general election, the US Department of State said of Kenya, ‘Drug barons use the proceeds to contribute to political campaigns and to buy influence with government officials, law enforcement officers, politicians, and the media.’

Second, this legislation gives judicial officers considerable leeway that they can abuse to let drug barons off the hook – or mete out very lenient sentences. Ideally, the weight of the sentence should depend on the amount of drugs and/or their street value. But as a look at some of the rulings shows, the prices are arbitrary. For instance, in Criminal Case 313 of 2010, some 20 grams of heroin were valued at Ksh200. But in Criminal Case 702 of 2010, in Kibera, 11.054 kilos were valued at Ksh11,054,000 (Ksh1 million per kilo). And in Criminal Case 1302 of 2010, Mombasa, 2 grams were valued at Ksh4,000.

There is also a wide discrepancy in the sentences. In Criminal Case 1176 of 2011, the Mombasa principal magistrate convicted George Awuor Mbwana to 10years and Ksh1 million for trafficking 10 sachets of heroin valued at Ksh3,000 – although this sentence would be reduced to five years in 2014 upon appeal. In Criminal Case 705 of 2009, the Malindi chief magistrate sentenced Carolyne Auma Majabu to life imprisonment plus a Ksh1 million fine for trafficking seven sachets of heroin valued at Ksh700.

According to UNODC’s Country Review Report of Kenya 2010-2015, there appear to be problems in regard to proportionality, consistency and adequacy in sentencing/convictions in cases related to drugs as well as economic crimes, such as money laundering.

Cartels Battle

A year ago, Nairobi Governor Evans Kidero complained about ‘state capture’ by organised criminals. Without mentioning their identity, he said they were providing Nairobi residents with free-of-charge services that are meant to be sources of revenue to counties. He said the underworld individuals were out to purchase political power by using the proceeds of drug trafficking.

This wasn’t the first time such a complaint had come up. Within and outside Kenya, people are convinced that the underworld is not only entrenched in Kenyan society, but that it is influencing the country’s political development. MPs, Senators and Governors, military and police officers, preachers and businesspeople are linked to trafficking but their identities are only mentioned in hushed tones.

None of them has been prosecuted or charged in court for their involvement in the illicit business.

In a report published after Kenya’s 2013 general election, the US Department of State said of Kenya, ‘Drug barons use the proceeds to contribute to political campaigns and to buy influence with government officials, law enforcement officers, politicians, and the media.’

According to CID sources, authorities have isolated four types of networks that drive the Kenyan drugs underworld: The loose or fluid network often cobbled together for a one-off deal – which collapses thereafter; the highly secretive patriarchal or kinship-based networks that control the illicit trade at the Coast; the upcountry syndicates that bring together mostly business allies and their political friends; and the trans-border cartels that bring together Kenyans and foreigners.

Cartels operate on political expediency. Specific cartels emerge during specific political seasons or regimes. That apart, the divisions – sometime blurred – may also be based on location or base of operation of the cartel, smuggling routes, and nationality and family links

Whatever type of network, close relationships among the players, also called nodes, are critical to their conduct and survival – what Margarita Dimova calls ‘compact, supple’ in the report, A New Agenda for Policing: Understanding the Heroin Trade in Eastern Africa.

Normally, the Kenyan cartels comprise just dozens of players who are mostly family members or business partners or acquaintances. Extra hands may be roped in case of extra load or work.

According to sources within the ANU, the cartels combine drug trafficking and smuggling (of humans and goods) and counterfeiting. Thus, Kenya’s underworld never lacks choices; drug lords can easily switch their business to conceal their tracks.

Interestingly though, the networks transform very fast in response to the changing political landscape. In the past 15 years, a number of cartels have collapsed while new ones have been formed to fill the void. The Mombasa-based Akasha organisation went down during President Kibaki’s regime while others emerged, linked to the new crop of politicians at the Coast and further inland.

It is important to note that churches have become key conduit for drug lords. In February 2014, a New Zealand missionary who often travelled to Nairobi was jailed for 12 years for trafficking 6.15 kilos of meths and 2.87 kilos of heroin, all valued at Ksh200 million, to Australia

Cartels operate on political expediency. Specific cartels emerge during specific political seasons or regimes. That apart, the divisions – sometime blurred – may also be based on location or base of operation of the cartel, smuggling routes, and nationality and family links.

Nairobi-based operatives, Kenyans and foreigners, depend on the airports and land routes to transact their illicit business. On the other hand, the so-called Coast Mafia has seized Mombasa port, airstrips at the coast, and myriad docking points on the Indian Ocean coastline.

BRIBING A GOVERNMENT ALREADY STEEPED IN CORRUPTION

For a long time, while Kanu was in power and Daniel arap Moi was president, the narco-trade was controlled from Kenya’s Coast, especially at the port and in Malindi. The Coast Mafia (including the Akashas and a former nominated MP based in Mombasa) and Europeans (Italians and Germans) were in firm command of the business. Kenyans and Nairobi-based West Africans (Nigerians, Ghanaians and Guineans) played the role of couriers or middlemen.

Drug lords used their ill-acquired proceeds to bribe a government that was already steeped in corruption. In the process, the kingpins were able to easily launder money by investing it in real estate, exports and imports, and in trans-shipment.

The Italians, after elbowing out the Germans, invested their proceeds in real estate – constructing 4,000 villas and homes along the beach and on second row plots. There were complains that the villas were hideouts for fugitives but the government did little to investigate the claims. It now emerges that convicted Italian fugitive Leone Alberto Fulvio used Malindi as a hideaway from Italian authorities for close to 23 years. While in Kenya, Fulvio got citizenship, a gun licence and a certificate of good conduct, and was cleared by the Kenya Revenue Authority. His cover would later be blown by the Interpol. He is now fighting extradition.

According to Frederico Varese, the author of the book Mafias on the Move: How Organised Crime Conquers New Territories, Malindi provides an ideal mafia revenue source, and a locale for money-laundering.

On the other hand, the Coast Mafia formed clearing and forwarding companies and got into export and imports and the transport business. And during Kibaki’s regime, they began setting up Container Freight Stations.

THE AKASHA EXTRADITIONS

Earlier this year, a specially selected team of Police officers assisted by America’s DEA spirited the so-called Akasha brothers – Baktash Akasha Abdalla and Ibrahim Akasha Abdalla – and their Indian cohorts Gulam Hussein and Vijaygiri Goswani to the United States to face charges of narco-trafficking.

US prosecutors who sought the extradition say their organisation is responsible for ‘production and distribution’ of large quantities of narcotics. ‘As alleged, the four defendants who arrived yesterday in New York ran a Kenyan drug trafficking organisation with global ambitions. For their alleged distribution of literally tonnes of narcotics – heroin and methamphetamine – around the globe, including to America, they will now face justice in a New York federal court,’ said Manhattan U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara.

The four were arrested in a sting operation originating with a Moroccan informer in November 2014. It came four months after the Vetted Unit seized 341 kilos of heroin concealed in a ship’s fuel tank.

But it wasn’t until after the murder of their father, Ibrahim Akasha, that Kenya woke up to the fact that it had its prototypical global drug lord. For a long time, Ibrahim, killed in Amsterdam in 2000, was the drug kingpin of the East African region. He controlled Mombasa port and landing sites between Kilifi and Vanga in the south of Mombasa. The Italians reigned unchallenged from Kilifi north to the Somalia border.

Ibrahim’s battles with local businessmen were muted and rarely became public because he never ventured out of the drug business, even as his rivals moved into transport, import and exports, and real estate to launder their profits.

He suffocated the West Africans, especially the Nigerians and Guineans, who were forced to take up the secondary role of couriers or middlemen from their bases in Nairobi. Other Kenyans who have since amassed wealth from drug trafficking also played second fiddle to the Akasha narco-machine.

The Akashas used Mombasa port to bring in heroin and hashish from Pakistan and cocaine from the Americas. It would then be blended with tea or coffee, to confuse sniffer dogs, and then packaged, ready for export to Europe and the United States. He also had associates who did the refining, dilution and repackaging

While the Akashas controlled the maritime routes, foreign networks held sway at the JKIA and the Moi International Airport in Eldoret.

The Akashas’ empire flourished because it was kinship-based. But two things happened that changed the fortunes of this cartel and placed it on a warpath with itself: Patriarch Ibrahim was murdered; and Mwai Kibaki replaced Moi as president of Kenya.

When Akasha senior was killed, his protégés/understudies were left splintered and in confusion. The death stoked a bitter feud within the family that led to several deaths. A number of Kibaki allies used their influence in Nairobi to target the Akashas and get into the business.

It has taken time for the Akashas to rebuild. Now they are part of the supply chain that stretches from the poppy fields of Afghanistan through India into East Africa. US authorities who extradited two of the Akasha sons and their Indian cohorts say their organisation is responsible for ‘production and distribution’ of large quantities of narcotics.

In India, it was reported last year that the Akasha organisation and their Indian collaborators had transported 100 kilos of morphine base, which can be refined into heroin, in January 2016. Some months ago, the Times of India newspaper reported on a plan by the Akasha sons and their Indian collaborators – Vicky Goswami and his former actress girlfriend Mamta Kulkarni – to set up a manufacturing and drug refining operation in Kenya.

ENTER THE EUROPEANS, EXIT THE NIGERIANS

European cartels have also moved into Kenya following the collapse of the Opium Trail. They managed to solidify their base during Kibaki’s regime by creating networks with Nigerians and local politicians.

In the decade from 2003 to 2013, this would morph into what Anti-Narcotics Unit sources called a ‘super cartel’ that roped in several MPs and foreign drug lords. It also recruited security and military personnel and powerful businessmen at the Coast.

The vicious cartel, which coalesced around close allies of president Kibaki, almost wiped out the Akashas and other networks of drug-lords cum politicians developed during president Moi’s time.

The super-cartel is alleged to have been behind the assassination on New Year’s Day 2006 of DCIO Hassan Abdillahi who had been tasked with investigating the theft of containers at the Mombasa Port. Three brothers of Kiambu governor William Kabogo (whom then US ambassador William Bellamy described in the Wikileaks cables as ‘known thug and rich-far-beyond-visible-means’) were arrested over the murder.

The cartel feared that the lead investigating officer was working with the Akashas to target them.

The government’s crackdown on the West Africans has created a void in the heroin trafficking business that has now attracted Kenyan, Tanzanian, Chinese, Indian and Eastern European cartels. Indeed, according to ANU sources, West Africans appear to have lost the heroin market to Asians, Tanzanians and Kenyans following the emergence of the Smack Track route. They had dominated this market so long that they had managed to push the pioneer drug-lords, including the Akashas, out of Nairobi, only to find themselves out of the loop when conflicts in North Africa and parts of Europe made the Turkey route impassable.

It is important to note that churches have become key conduit for drug lords. In February 2014, a New Zealand missionary who often travelled to Nairobi was jailed for 12 years for trafficking 6.15 kilos of meths and 2.87 kilos of heroin, all valued at Ksh200 million, to Australia. Ms Bernadine Terry Prince (aka Pastor Bernie McCully), 42, who was married to a Nigerian, was arrested after she had toured Nairobi, Nigeria, and Cambodia. She claimed she was the Australian chief executive of Oasis of Grace Foundation that has affiliates in Kenya, Ghana, and several other countries. She was a missionary with Oasis of Grace International Church in Nairobi’s Kayole Estate.

Prior to her arrest, she had attended a conference in Nairobi and later spent time in Nigeria and Cambodia. In her defence she claimed that a Kenyan, Mummy Rose, her given her seven backpacks with handicrafts to sell in Australia. The court found drugs and not handicrafts.

President Uhuru Kenyatta has moved to dismantle the cartels that formed during Kibaki era. But his war is unstructured and some of those he is targeting are close allies of his friends. Uhuru first targeted foreigners, clipped the wings of a cartel run by a former assistant minister and later trained his guns on the Coast Mafia, including Joho’s family.

A Senator allied to the ruling party runs a trafficking network that operates from Wilson Airport. According to senior military officials who have served in Somalia, as at last year, authorities in Somalia had confiscated two containers destined for Kenya that belonged to the Senator. ‘One had electronics and the other had a white substance. We couldn’t isolate the substance so it was anybody’s guess,’ a Somali official said. The military officer has since been redeployed elsewhere so it’s still not clear what happened to the containers.

According to the International Drugs Policy Consortium, a policy network that promotes open discussion on drug policy, the Kenya-Somalia border is a playground for drug cartels that operate without fear of being detected

‘Local and international drug smugglers are taking advantage of the limited resources of security forces and borders control like, for example, on the border between Kenya and Somalia where drug smugglers can operate without being detected,’ says the consortium report.

But, in an interview for this report, police spokesperson George Kinoti denied knowledge of the Somalia route. ‘So far, we have not been able to detect drugs trafficking on the Somalia route. The route has not been known for drugs coming to Kenya.’

The Mail&Guardian warns that drugs, crime and dirty money are so entrenched in Kenya that any threat to destabilise this underworld could actually be detrimental to the entire economy

STATE CHALLENGE: NO COHERENT RESPONSE

Kenya’s anti-drugs war is characterised by haphazard half-measures. Authorities appear to dither even as the prevalence of trafficking – illustrated by the number of couriers in jails and large seizure amounts – continues to rise. There hasn’t been a coherent response to the menace. Indeed, responses have oscillated from ‘mute, bizarre or half-hearted reactions, to outright lies to bold admission,’ according to a Western diplomat.

In a recent interview, Kinoti said, ‘Here in Kenya, I can say drug trafficking is a challenge but not a huge problem. Our security agencies are up to the task when it comes to dealing with drug trafficking.’

Hamisi Masa, the ANU boss, told Reuters, ‘Now, it is not just about us here in Kenya …The whole world is involved.’

When he destroyed a vessel seized with 370 kilos of heroin in 2014, President Kenyatta thundered, ‘We will not allow drug barons to destroy the future of our young people. We will track and deal with them decisively.’ Commenting on the destruction, John Mututho, the NACADA boss, promised to reveal the people behind the narco business in Kenya. ‘We are investigating 50 suspected drug barons and we are sure we will recommend action by the end of the year.’

After more than two years, no names have been released.

Few believe the government is serious in its war against the drug barons

Narcotics Impact

The Mail & Guardian, a leading South African newspaper, warned in a recent report that Kenya was hurtling towards becoming Africa’s second ‘narco-state’ after Guinea Bissau. Titled The Making of an African Narco State, the news piece warns that drugs, crime and dirty money are so entrenched in Kenya that any threat to destabilise this underworld could actually be detrimental to the entire economy. ‘Kenya is emerging as a money laundering hub; incredibly, trying to stop the illicit flow of money could hurt the economy more than letting it continue.’

(A narco-state, according to Collins English Dictionary, is ‘a country in which the illegal trade in narcotics drugs forms a substantial part of the economy.’)

‘We are in deep trouble,’ a senior anti-narcotics officer told this writer. ‘The security agencies, the police, the politicians and some mandarins are either in bed with the drug barons or are the kingpins. You cannot isolate the barons.’

According to reports, more than 3,000 Kenyans are rotting in foreign jails, with some serving life sentences while others await execution. Others have died in jails abroad. About 3,000 are in local jails, convicted over hard drugs. The politics of Kenya’s major towns, Nairobi and Mombasa, is now influenced by drugs. While some drug-lords hold top offices in the country – two governors, a Senator, several MPs and other politicians are on the radar of the Vetted Unit, others, including top bureaucrats, police and judicial officers, provide protection to the barons.

‘We are in deep trouble,’ a senior anti-narcotics officer told this writer, but asked that his name not to be published lest he offended his bosses, some whom are allies of known drug barons. ‘Will we get out this? I doubt it. The arresting agency is a prisoner too. In fact, the security agencies, the police, the politicians and some mandarins are either in bed with the drug barons or are the kingpins. You cannot isolate the barons.’

Undeniably, Kenya is a major trafficking hub for drugs. It also has a growing consumption problem. Those interviewed for this report detailed a number of approaches that can help defeat traffickers and trafficking: Detect, deter and interdict. It needs strengthening of the country’s data collection systems, international co-operation, effective border controls, and law enforcement.