Nairobi, Kenya – AGENDA NUMBER ONE IS POMBE

In July 2015, Kenya’s President Uhuru Kenyatta summoned Members of Parliament from the country’s central region to State House in Nairobi. ‘We must agree we have a problem that needs immediate action,’ he told them, declaring ‘agenda number one is pombe (alcohol), number two is pombe and three is pombe.’

The president stated that the country was in the throes of a drinking crisis fuelled by the availability of cheap, illicit alcohol, with dire warnings of an entire generation being lost to booze. So alarmed was he that he ordered the assembled legislators, the paramilitary police and the citizenry ‘to move from door to door closing all outlets selling the illicit drinks.’

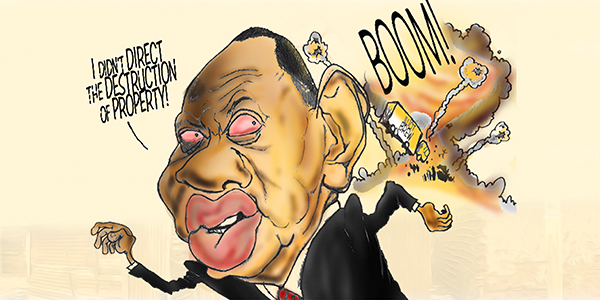

The hysteria he whipped up resulted in the widespread destruction and looting of business premises by rampaging mobs under the guise of implementing the directive. And though the President later attempted to walk back his fierce talk by urging that property be respected, and despite the courts ruling his order unconstitutional, the damage had already been done. Hundreds of legitimate businesses lay in ruin and the country’s biggest brewer, East African Breweries, reported losses of up to Ksh250 million ($2.5 million) in the first week of the crackdown alone.

The hysteria President Kenyatta whipped up resulted in the widespread destruction and looting of business premises by rampaging mobs under the guise of implementing his directive

Yet the crisis the president was bemoaning was all of his own making. As Jane Karuku, managing director of Kenya Breweries Ltd, wrote, about three years prior, the government had raised taxes on keg beer, a low-end beer, in a bid to boost revenue collection. Prior to this, demand for the product had been growing steadily, its affordability weaning a significant number of people off dangerous illicit drinks. By precipitating a steep 40% rise in consumer prices, the tax increase stopped this in its tracks.

The resulting vacuum was filled by what came to be known as ‘second generation alcohol.’ These are cheap, low quality, highly potent spirits produced by poorly regulated small scale manufacturers. By November 2015, according to a report by the Inter-Agency Task Force on Control of Potable Spirits and Combat of Illicit Brews set up to enforce the president’s directive, there were 200 registered alcohol makers, only 10% of whom were actually considered fit to do so.

NO DATA TO SUPPORT A CRISIS

Also lost in all the chaos was the fact that there is little publicly available data to support the idea of a widespread crisis of intoxication among young men in Kenya. On the contrary, a 2012 report by the National Authority for the Campaign against Alcohol and Drug Abuse (NACADA) showed that alcohol consumption in central Kenya, the purported epicentre of the crisis, had actually fallen by 10% in the previous five years. Another study, carried out two years prior, found that more than two-thirds of those surveyed were lifetime abstainers.

According to the WHO’s Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2014, which cites data from 2010, nearly 8 in 10 Kenyans aged 15 and above had not had a drink in the previous 12 months. This figure includes the half of all similarly aged males who were lifetime abstainers and another sixth who appear to have given it up. In all, nearly 7 in 10 males and 9 in 10 females over 15 were not partial to alcohol.

In fact, Kenya would be the East Africa Community’s designated driver, with between 40% and 45% of Tanzanians, Rwandans, Burundians and Ugandans being alcohol consumers.

Among those Kenyans who partook, only 7.4% had taken more than 60 grams or more of pure alcohol (roughly the equivalent of three bottles of Tusker) on at least one occasion in the previous 30 days. These figures did not reveal a generation of Kenyans drinking themselves into an early grave.

However, the 2010 NACADA study did find that more young men in central Kenya had taken to drinking compared with 2007 – the prevalence rate among those aged 15-64 had shot up by 11.5%. However, when broken down into the several districts, the data revealed that consumption in some was much higher than in others, indicating localised pockets of crapulence.

According to the WHO’s Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2014, which cites data from 2010, nearly 8 in 10 Kenyans aged 15 and above had not had a drink in the previous 12 months

What they were drinking was also interesting, with figures showing that about half were imbibing alcohol that, according to NACADA, can be assumed to be of hygienic standard and moderate potency. Second generation alcohol and chang’aa, which were the cause of most concern, accounted for 40% and 1.5% respectively, while the rest, just under 10%, drank traditional brews.

KENYATTA MASKED AN ILLICIT PROBLEM CREATED BY HIS OWN POLICIES

President Kenyatta was in essence masking an illicit alcohol problem created by his own policies by inventing a nationwide crisis of alcoholism. Yes, there were localised pockets of crapulence in the country and the folks there require help, not demonisation. It is not illegal to be an alcoholic and treating such people, and the legitimate enterprises that are licensed to sell booze, as if they were criminals is counterproductive.

It is also important that we have an accurate understanding of what is and what is not illicit. It certainly does not appear that the trade in the much maligned second-generation alcohol is actually illegal. When the Kenya Bureau of Standards suspended 385 brands following the president’s directive, it also acknowledged that they were legal, with its managing director saying the concern was with counterfeiters.

Undoubtedly, adulterated and bootleg alcohol has caused many deaths over the years. Chang’aa, Kenya’s kill-me-quick moonshine, a clear, colourless mix of distilled maize, millet, sorghum and a host of other not necessarily legal ingredients, was a major target of the current crackdown. But across the country, chang’aa takes many forms and is not always illegal or dangerous. In an article in the Star, John Githongo avers that chang’aa brewed in a western Kenya pot is much safer and of much better quality than its central Kenya counterpart. It is also consumed much more widely, with little or no ill-effects. It also bears reminding that though most chang’aa is made illegally, its production and sale can be a legitimate enterprise. The 2010 Alcoholic Drinks Control Act repealed the Chang’aa Prohibition Act, which made it illegal to produce or consume traditional liquors.

The fact that all chang’aa, along with the ill-defined category of second generation booze, appears to be treated as if it were illicit arose from a failure to properly identify the problem and to acknowledge the factors driving it. Aside from covering up the president’s mistakes, the policy reflects the state’s historic discomfort and fear of drinking by the poor. These two trends have led us inexorably down the path of futile, unworkable and frankly self-defeating attempts at alcohol regulation.

Official unease at drinking by the underprivileged, especially – though not confined to – the central province, dates back to pre-colonial times and in more recent history has reflected British racist and class stereotypes. Most traditional societies closely regulated the production and consumption of alcohol, with drinking being the exclusive preserve of male elders. There were dire warnings about the consequences of youthful indulgence, which was perceived as a threat to the existing social organisation.

Colonialism seriously undermined the power of elders both through the appointment of low-level bureaucrats as chiefs and the introduction of wage labour, which gave the youth independent means of procuring or producing their own hooch. This very independence however worried the new powers. In the essay Drunks, Brewers and Chiefs: Alcohol Regulation in Colonial Kenya, 1900-1939, Prof Charles Ambler, professor of history at the University of Texas at El Paso, dates British efforts to control native alcohol consumption to the earliest days of the colonial enterprise. Enforcement of the 1890 Act of Brussels, which banned the export of spirits to East Africa, while ‘consistently and forcefully keeping such liquor out of the hands of Africans’ did little to restrict consumption among white settlers.

The policy reflects the state’s historic discomfort and fear of drinking by the poor. These two trends have led us inexorably down the path of futile, unworkable and frankly self-defeating attempts at alcohol regulation

The following decades saw enactment of laws criminalising drinking by Kenyans under 30, public drunkenness and restricting access to raw materials used in the manufacture of booze, particularly in the central province. This was despite the paucity of evidence for an ‘epidemic of drunkenness’ and probably had more to do with official insecurities. ‘Drinking made Africans both unpredictable and dangerous, in the process eroding the veneer of obeisance that made control possible … and permitted one or two British officials to rule vast districts with apparent ease.’ Significantly, as Ambler goes on to note, periods of rigorous alcohol regulation coincided with heightened political and social unrest.

WE NEED LABOUR; THE AFRICAN CANNOT HOLD HIS LIQUOR… ERGO

Another motive for controlling alcohol use among the natives was the colonial economy’s requirement for local labour and the perception that Africans could not hold their liquor. ‘Greater attention was focused on the role of drinking in discouraging young men from engaging in wage labour.’ From early on, restrictions on African drinking hours sought to impose an industrial regime on previously agricultural societies. In the article, Alcohol Licensing Hours: Time and Temperance in Kenya, Justin Willis writes: ‘Regulation began with the prohibition of all-night drinking, then moved to the imposition of more detailed daily and calendric rhythms, driven by the perceived need to regulate the leisure time of wage labour.’

At Independence, these laws and attitudes were adopted, and in some cases enhanced, by the ruling African elite who kept for themselves the privileges formerly reserved for the whites. Jomo Kenyatta, who once traded in Nubian gin – a euphemism for Nubian chang’aa – in Dagoretti, had no qualms about further restricting drinking hours though, as in the colonial era, enforcement was and continues to be, sporadic.

However, as the enduring colonial distinction between the approved settler booze and illegal native liquor continued, the law produced divergent drinking cultures among the urban workers – with the former consumed mainly by the middle-class in legitimate enterprises after working hours and on weekends and the latter by the poor pretty much throughout the day in illegal dens. Like the colonial settlers whose drinking was not adjudged to interfere with public order and thus required little regulation, the elite can drink to their heart’s content at any time of the day in private clubs without courting opprobrium.

In the 1990s, as donors turned off the taps and the economy went south, the government turned to excise taxes on beer in a bid to plug the hole in its finances. Following the 1992 elections, taxation on bottled beer rose to 153% per unit. With per capita incomes shrinking throughout the decade, this had the effect of driving legitimate booze out of reach of ever increasing numbers of people, including some in the middle-class.

Jomo Kenyatta, who once traded in Nubian gin – a euphemism for Nubian chang’aa – in Dagoretti, had no qualms about further restricting drinking hours though, as in the colonial era, enforcement was and continues to be, sporadic

Into this void stepped a new kind of alcoholic beverage. According to Willis, in a 2003 article titled New Generation Drinking: The Uncertain Boundaries of Criminal Enterprise in Modern Kenya, what came to be known as second generation drinks ‘disturbed an established boundary between the formal and informal sectors, and between legitimate enterprise and criminal endeavour.’ Although packaged as ‘modern’ drinks, they were classed as ‘traditional,’ and attracted excise tax of just 10%. In terms of alcohol content, ‘power drinks’ were four to five times cheaper than the fare from the market monopoly, EABL, and successfully competed for the lower end of the market.

Despite periodic bans, the drinks have continued to be sold. As evidenced by the latest ‘crackdown,’ government agencies continue to issue confused and conflicting statements about the legality and safety of the drinks. As noted above, many are licensed and produced on an industrial scale in premises whose locations are well known.

Beginning 2004, the Kibaki government began to reduce duty on non-malted beer, eliminating it altogether in 2006. The aim was to offer people on the lower end of the market a clean and affordable alcoholic drink. Prices for EABL’s sorghum beer, Senator Keg, did indeed fall and compared favourably with most ‘illicit’ brews and, EABL claimed, captured half their market. But this was no silver bullet. Among the poorer customers, the higher alcohol content of illicit brews still made them more attractive. In the end, the government was forced to legalise chang’aa in 2010. This gave the poor an even wider choice of legal and safe alcohol.

But, as Jane Karuku observed, the Uhuru administration restored the excise tax on sorghum beer, nearly doubling its price overnight. According to EABL, the price increase cut sales of Senator Keg by 80% as its poorer customers trooped back to the shadowy worlds of chang’aa and second generation drinks.

The current hoopla about boozing is merely a continuation of a centuries-old experiment in social and political control, couched in the language of a patronising concern. The echoes of the official terror of drinking as an obstacle to control can also be heard in the oft-repeated description of youthful protesters as drunk or drug-addled. In other words, as was feared by the colonials, inebriation prevents those in the lower ranks from accepting their proper place in the pecking order.

CRIMINALISATION IS HYPOCRISY

The de facto criminalisation of drinking by the poor is hypocritical given that the president himself is widely rumoured to be a something of a drinker. ‘He drinks too much,’ wrote former US ambassador to Kenya Michael Ranneberger in a leaked 2009 cable. But even worse, it produces effects that are diametrically opposed to the declared aims. Alcohol control policies have mostly not been informed by accurate assessments of the prevailing situation or their effects on actual drinking habits. Thus ill-advised bans and taxes have driven the approved booze out of reach of the poor while at the same time driving most of the trade in native liquor underground and making it much more dangerous.

Crackdowns thus compound, not solve, the problem. To do so, the government must first recognise that Kenya does not have a drinking problem. It has a policy and regulation problem. It is the policy regime that creates perverse incentives for the adulteration of drinks, killing many. This will only be cured by an enlightened, rational, evidence-based approach that prioritises, not prohibition, but affordable, legal and safe hooch for the poor. In short, the best way to deal with Kenya’s alcohol problem is for the government to sober up.