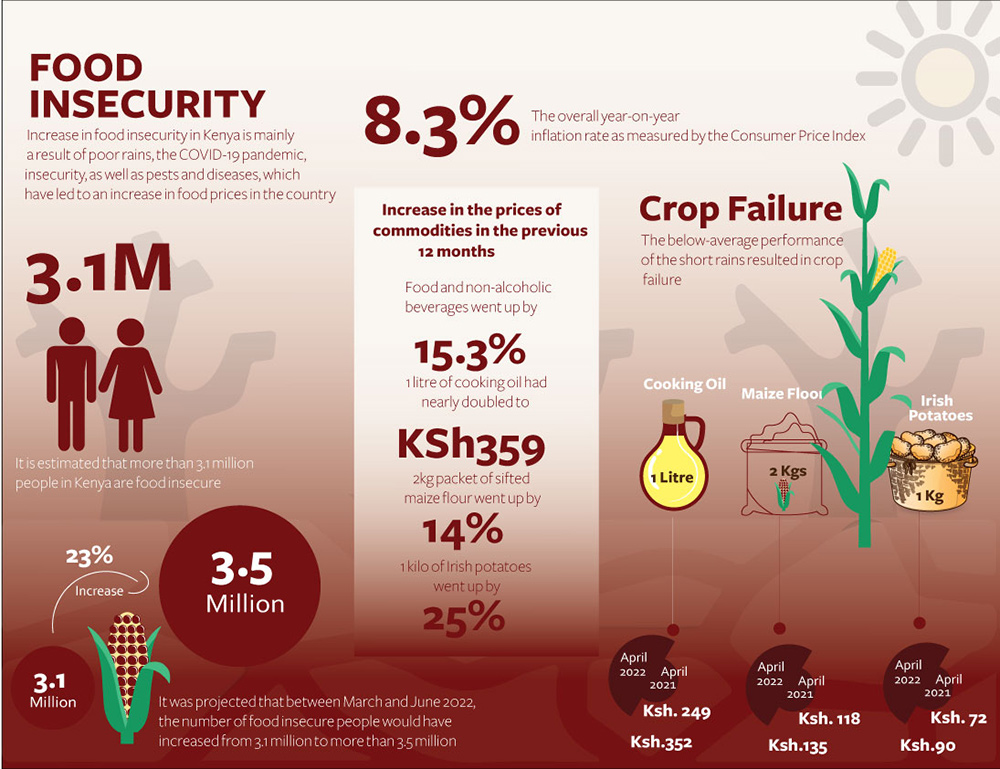

On 8th September 2021, the then president of Kenya, Uhuru Kenyatta, declared the drought affecting several parts of the country a national disaster. The increase in food insecurity in Kenya is mainly a result of poor rains, the COVID-19 pandemic, insecurity, as well as pests and diseases, which have led to an increase in food prices in the country.

Kenya has been experiencing a high inflation rate since the beginning of 2022. In July 2022, the overall year-on-year inflation rate as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI) was 8.3 per cent. This was mainly due to an increase in commodities prices in the previous 12 months, including food and non-alcoholic beverages, which on average had gone up by 15.3 per cent. The cost of a litre of cooking oil had nearly doubled to KSh359, while that of a 2-kilogramme packet of sifted maize flour, a local staple, had gone up by 14 per cent, and a kilo of Irish potatoes by 25 per cent.

A March 2022 report by the National Drought Management Authority (NDMA) estimated that by June, a quarter of the population in Kenya’s arid and semi-arid (ASAL) counties, or more than than 3.5 million people, would be acutely food insecure, with those in Marsabit, Turkana, Baringo, Wajir, Mandera, Samburu and Isiolo counties, who mostly depend on pastoralism for their livelihoods, being the most affected.

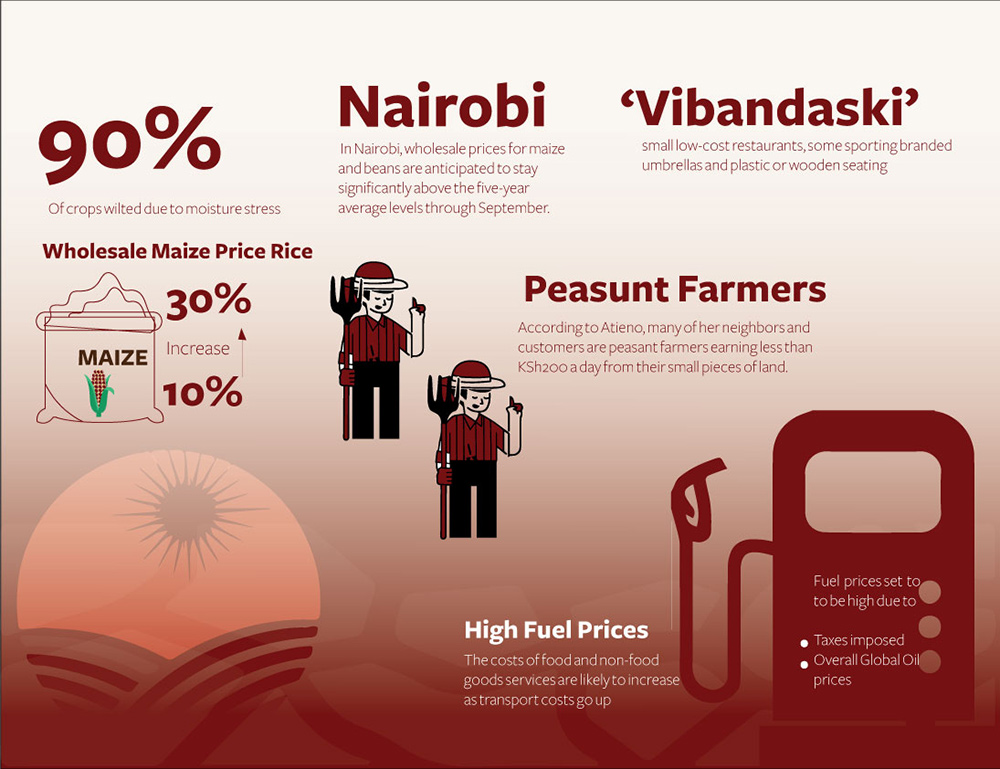

Many Kenyan households are trying to find alternatives to survive given the trends in food prices. Some in Nairobi have turned to Vibandaski—small low-cost restaurants, some sporting branded umbrellas and plastic or wooden chairs. Kamau Njoroge, who works at a construction site, says he prefers the kibandaski to cooking at home. “To make breakfast at home, I’d have to buy a packet of milk at KSh60, sugar at Ksh120, tea leaves, and a loaf of bread that is KSh60.” This is more than his daily wage of KSh200. “Compare that with the breakfast at the kibandaski which costs Ksh20,” he says.

Hellen Atieno is a trader and a small-scale farmer who has been doing business in Kisumu town for the past five years. She has a shop that stocks staple foods in the area where she buys the goods wholesale and sells them to her customers at retail prices.

Atieno narrates says that the prices of goods at the wholesaler have doubled since she started her business. “When I started my business in 2017,” she says, “I would buy 50 kilos of sugar at KSh3,000, 20 litres of cooking oil at KSh2,500 and a bundle of a dozen 2-kilogramme packets of maize flour at KSh600. Those prices have changed and currently I am buying the sugar at Ksh6,500, oil at KSh6,000 and maize at KSh1,600.”

Atieno says she has to employ different selling techniques to accommodate customers unable to afford the higher prices. For example, she used to repackage the cooking oil into 300ml soda bottles, but as prices have increased, she now also repackages into smaller quantities measured out using a stainless steel cup.

According to Atieno, many of her neighbours and customers are peasant farmers earning less than KSh200 a day from their small pieces of land. Many are forced to skip meals, surviving on only one or two meals a day. Atieno adds that poor rains have also severely reduced the produce from her farm. “I used to harvest 6 sacks of maize from my quarter-acre and right now I can only get two sacks,” she says.

The situation is worse in the ASAL counties where, according to the NDMA report, households only have stocks that can last one to two months instead of the normal three to six months as a consequence of poor rains and the cumulative effect of the previous poor seasons. “In some counties, total crop failure of maize and cowpeas was expected, as the crops wilted at germination and vegetative stages,” according to the report. Exacerbated by limited access to farm inputs and Fall Armyworm invasions, the production of these crops as well as green grams at the coast has fallen below five-year averages.

Even outside the dry counties, high food prices are expected to remain the norm, notwithstanding government efforts to introduce subsidies. In Nairobi, wholesale prices for maize and beans are anticipated to stay significantly above the five-year average levels through September. With local fuel prices expected to reflect overall high global oil prices, this signals more tough times ahead for people across the country.

–

This article is part of The Elephant Food Edition Series done in collaboration with Route to Food Initiative (RTFI). Views expressed in the article are not necessarily those of the RTFI.