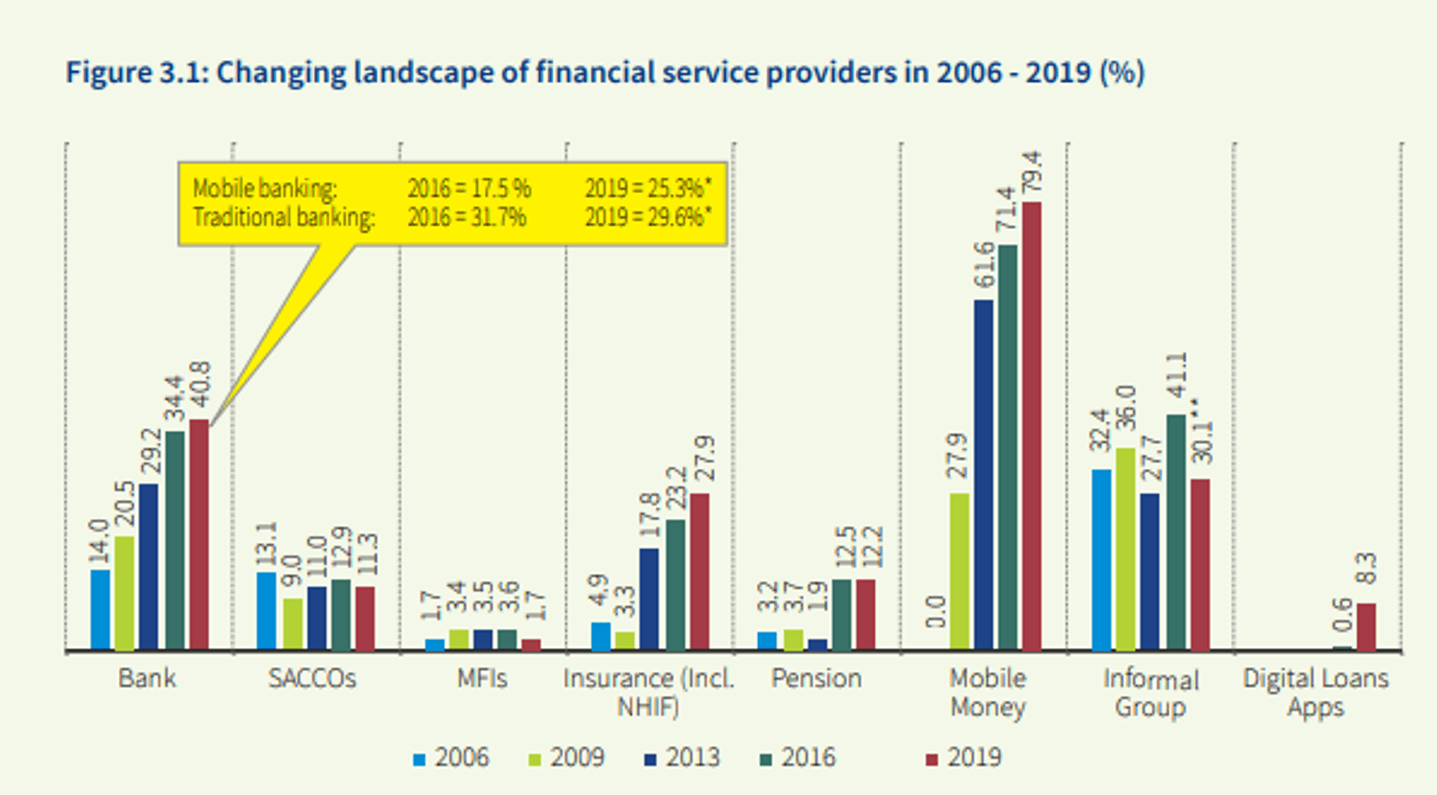

Kenya’s financial inclusion has drastically improved in the last couple of years through development in the financial sector. Mobile money has been a key driver in narrowing the financial access gap in Kenya.

According to FSD Kenya, M-Pesa, Safaricom’s mobile money platform, is said to have lifted 2% of Kenyans out of poverty.

The impact is more significant in female-headed households, which had previously been limited in accessing financial services due to cultural restrictions. Financial access growth has reduced the gender gap from 13% to 6%.

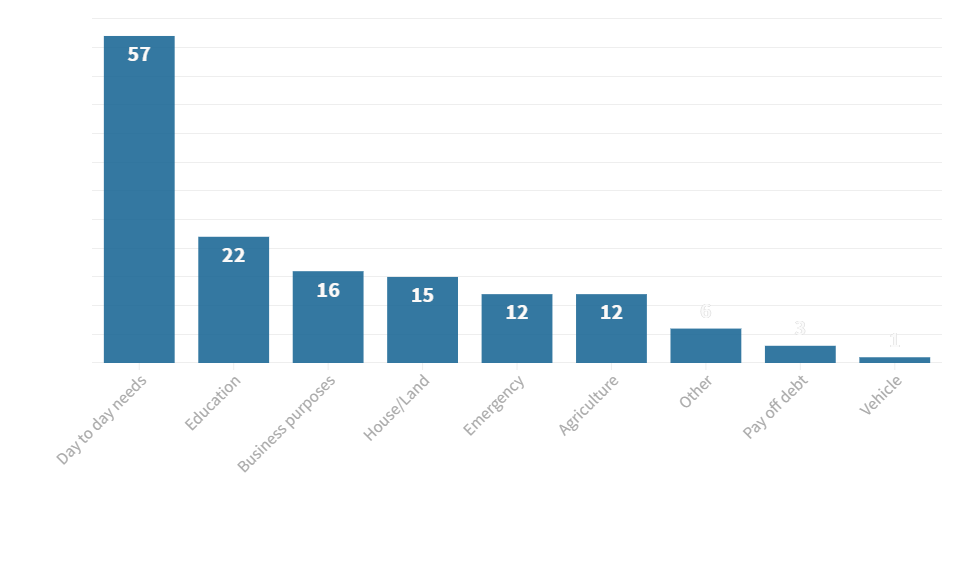

Mobile money has been the main financial service used by all socio-economic groups in Kenya. It has prompted the entrance of several private investors into Kenya’s credit market as the demand for quick, small loans has been growing rapidly. In the first quarter of 2020, loan accounts in Kenya increased by 21% compared to the last quarter of 2019. About 92% of these accounts were mobile loans. Another common source of finance for Kenyans, especially the lower-income groups has been chamas. These groups offer loans to members at about 1% per month. Mobile loans and chamas have been falling through the cracks of formal lending systems, providing the lower-income groups with capital to pay school fees, do farming, expand their businesses and meet daily expenses.

Reasons for taking credit

Financial options for the poor are falling flat…

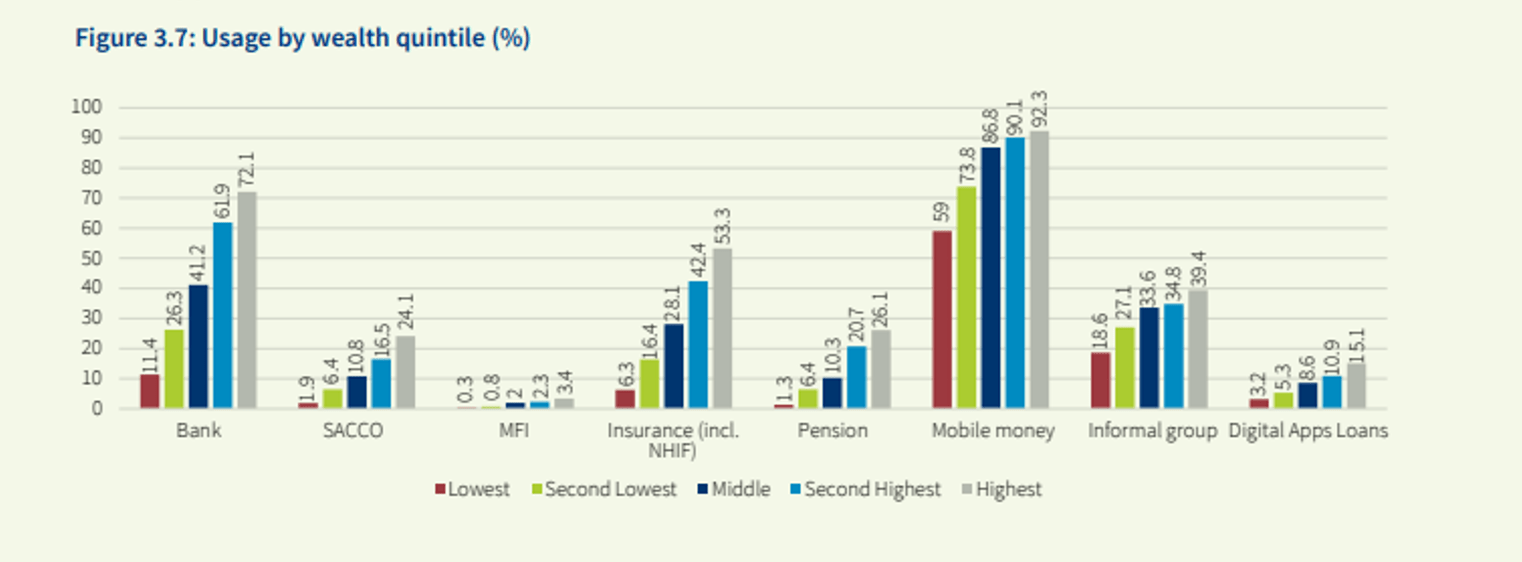

The financial services used by Kenya’s most vulnerable groups are mobile money, informal groups, banks, insurance (mostly NHIF) and digital loans.

Luckily, the low-income groups can still comfortably use mobile money, especially since the Central bank extended the waiver of M-pesa fees for transactions equal to or below Kshs 1,000. However, they are unable to access mobile loans. In April, when the Central Bank of Kenya barred mobile lenders from forwarding the names of loan defaulters to credit reference bureaus (CRBs) and stopped the blacklisting of borrowers owing less than Kshs 1,000, most mobile loan companies ceased loan disbursements and focused on getting repayments from the funds disbursed pre-COVID-19.

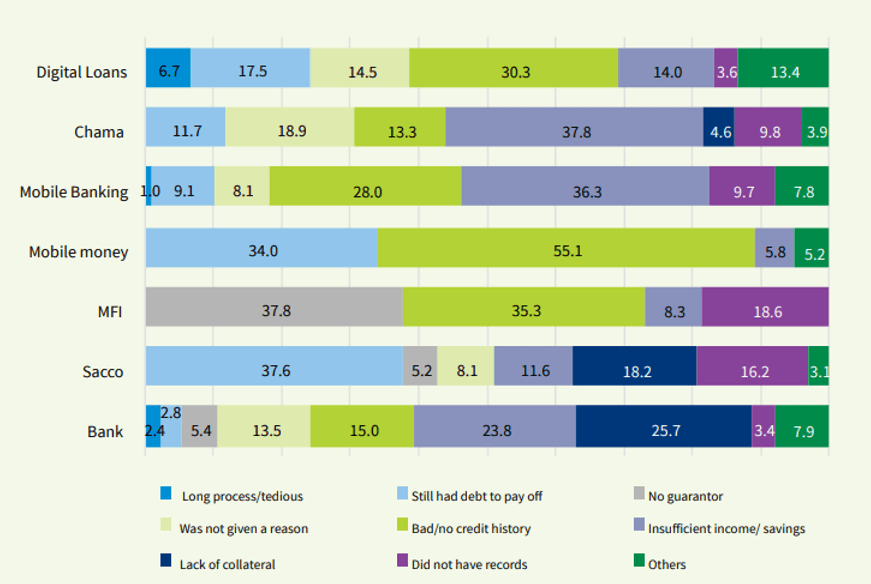

Usually, SACCO customers are mainly denied credit on account of failure to clear outstanding loans. Mobile money, mobile banking and digital loan apps providers deny customers credit on a bad or no credit history. Lower-income groups are the majority who make up Kenya’s informal sector or part-time workers in the formal sector who were the first to be culled from the workforce because of the economic impact of COVID-19. Many have been unable to repay their loans, and financial institutions are avoiding taking up more risks by lending to this consumer segment.

Reasons for being denied credit by the institution in 2019

Low-income groups lack the financial cushion of adequate savings and have had to find new ways to survive

For those using informal groups to access finance, the main reason for being denied credit is usually low savings. In the first few weeks of the COVID-19 outbreak in Kenya, low-income groups depleted their savings, and now members of these informal groups are unable to raise their monthly contributions.

As financial services appear to have fallen flat, Kenya’s low-income groups have resorted to selling their assets, skipping meals, looking for a new start in their rural homes, amongst other measures they are taking to survive.

Microfinance institutions and mobile loan companies now face threats to their own existence. These institutions do not have a fall back market, as they rely solely on their shareholders or depositors. The commercial nature of these companies puts a heavy amount of pressure on borrowers who pay very high annualised interest rates of over 130%. If left unregulated, these players can end up increasing poverty. Some households have reported being much more afraid of their inability to repay their debt to these institutions than they are of the coronavirus.The Central Bank has stepped in to help borrowers by supervising digital lending for the first time. It has proposed a law that will see it regulate monthly interest charged by the mobile loan companies and borrowers’ non-performing loans.

Whereas the new regulations would protect borrowers, there’s another side to the coin. If the new regulations by the Central Bank of Kenya put microfinance institutions under stress, low-income households’ will be unable to access credit, and their ability to maintain livelihoods will be affected. There needs to be a delicate balance of measures put in place through a collaborative effort between international donors, financial institutions and the government. Stakeholders need to not only create adequate consumer protection legislation but also implement measures that will sustain microloan services to Kenya’s most vulnerable.

–

This article was first published by Africa Uncensored’s Piga Firimbi.