Diseases have plagued mankind throughout history. The Neolithic Revolution, which was marked by a shift to agrarian societies, preceded by hunting and gathering communities, brought about increased trading activities. The shift created new opportunities for increased human and animal interactions, which in turn, introduced and sped up the spread of new diseases. The more civilized humans became, the more the occurrences of pandemics was witnessed.

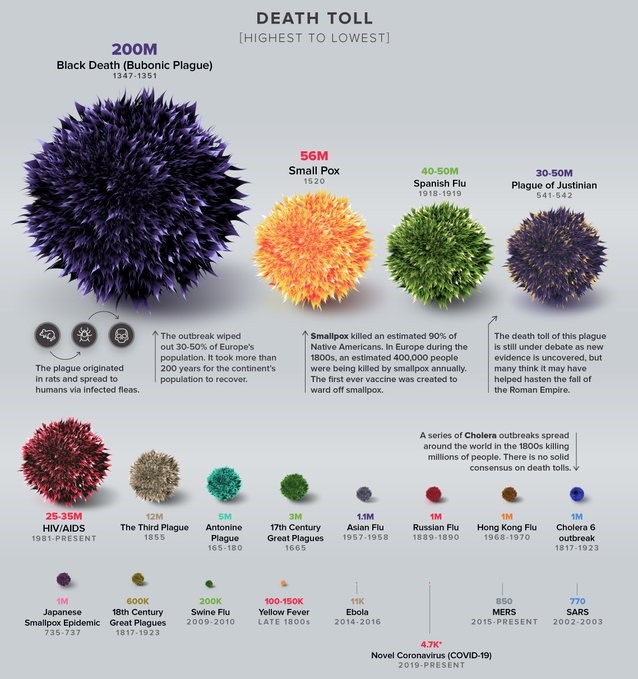

This led to outbreaks that left an indelible mark in history due to their severity. Three of the deadliest pandemics include the Plague of Justinian (541-542 BC) that killed about 30-50 million people, Black Death (1347-1351) that killed 200 million and Smallpox (1520 onwards) that killed 56 million.

In modern history, the most notable major pandemic was the Spanish Flu of 1918-1919. Over a century later, the world is grappling with the effects of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic that has currently infected over 2 million people and killed over 140,000.

But how does the Spanish flu compare to the current COVID-19 pandemic?

The mother of all flu pandemics in modern history

The Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 is sometimes referred to as the mother of all pandemics. It affected one-third of the world’s population and killed up to 50 million people, including some 675,000 Americans. It was the first known pandemic to involve the H1N1 virus.

The outbreak occurred during the final months of World War I. It came in several waves but its origin, however, is still a matter of debate to-date. Its name doesn’t necessarily mean it came from Spain.

Spain was one of the earliest countries where the epidemic was identified. Historians believe this was likely a result of wartime media censorship. The country was a neutral nation during the war and did not enforce strict censorship on its press. This freedom of the press allowed them to freely publish early accounts of the illness. As a result, people falsely believed the illness was specific to Spain and hence earning the name “Spanish flu”.

Symptoms

Influenza or flu is a virus that attacks the respiratory system and is highly contagious.

Initial symptoms of the Spanish flu included a sore head and tiredness, followed by a dry hacking cough, loss of appetite, stomach problems and excessive sweating. As it progressed, the illness could affect the respiratory organs, and pneumonia could develop. This stage was often the main cause of death. This also explains why it is difficult to determine exact numbers killed by the flu, as the listed cause of death was often something other than the flu.

These symptoms are very similar to those of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Origin

For decades, the Spanish flu virus was lost to history and scientists still do not know for sure where the virus originated. Several theories as to what may have caused it point to France, the United States or China.

Research published in 1999 by a British team, led by virologist John Oxford theorized a major United Kingdom staging and hospital camp in Étaples, France as being the centre of the flu. In late 1917, military pathologists reported the onset of a new disease with high mortality in the overcrowded camp that they later recognized as the flu. The camp was also home to a piggery, and poultry was regularly brought for food from neighbouring villages. Oxford and his team theorized that a significant precursor virus harboured in birds, mutated and then migrated to the pigs.

Other statements have been that the flu originated from the United States, in Kansas. In 2018, another study found evidence against the flu originating from Kansas, as the cases and deaths there were fewer than those in New York City in the same period. The study did, however, find evidence suggesting that the virus may have been of North American Origin, though it wasn’t conclusive.

Multiple studies have placed the origin of the flu in China. The country had lower rates of flu mortality, which may have been due to an already acquired immunity possessed by the population. The argument was that the virus was imported to Europe via infected Chinese and Southeast Asian soldiers and workers headed across the Atlantic.

However, the Chinese Medical Association Journal published a report in 2016 with evidence that the 1918 virus had been circulating in the European armies for months and possibly years before the Spanish flu pandemic.

COVID-19, on the other hand, was first discovered in the Wuhan province of China late last year. There has been no argument against this so far. Research is still ongoing as to whether it was passed on from bats or the newly found connection to pangolins.

Spread

Much like COVID-19, the Spanish flu was spread from through air droplets, when an infected person sneezed or coughed, releasing more than half a million-virus particles that came into contact with uninfected people.

The close quarters and massive troop movements during the war hastened the spread of the flu. There are speculations that the soldiers’ already weakened immune systems were increasingly made vulnerable due to malnourishment and the stresses of combat and chemical attacks. More U.S soldiers in WW1 died from the flu than from the war.

A unique characteristic of the virus was the high death rate it caused among healthy adults 15-34 years of age. It lowered the average life expectancy in the U.S by more than 12 years.

COVID-19, on the other hand, does not discriminate in terms of age, but older people and those with other underlying medical conditions are being considered more vulnerable.

Measures

The measures being taken today to curb the spread of COVID-19 are very similar to those taken in 1918. Back then, physicians advised people to avoid crowded places and shaking hands with other people. Others suggested remedies included eating cinnamon, drinking wine and drinking Oxo’s beef broth. They also told people to keep their mouths and noses covered with masks in public.

In other areas quarantines were imposed and public places such as schools, theatres and churches were closed. Libraries stopped lending books and strict sanitary measures were passed to make spitting in the streets illegal.

Due to World War I, there was a shortage of doctors in some areas. Many of the physicians who were left became ill themselves. Schools and other buildings were turned into makeshift hospitals, where medical students had to step up to help the overwhelmed physicians.

Effects

Though the severity of COVID-19 has not gotten to the level of the Spanish flu, most of the effects the world is experiencing now are very relatable.

The Spanish flu killed with reckless abandon, leaving bodies piled up to such an extent that funeral parlours and cemeteries were overwhelmed. Family members were left to dig graves for their deceased loved ones. Strained state and local health centres also closed, hampering efforts to chronicle the spread of the flu and provide much-needed information to the public. Similar scenes are being witnessed in Italy today, which has so far recorded the highest number of deaths due to COVID-19.

The Spanish flu also adversely affected the economy as the deaths created a shortage of farmworkers, which in turn affected the summer harvest. A lack of staff and resources put other basic services such as waste collection and mail delivery under pressure. COVID-19 has seen some companies send their employees home on unpaid leave and others have imposed pay cuts. If the situation worsens, a majority is likely to lose their jobs.

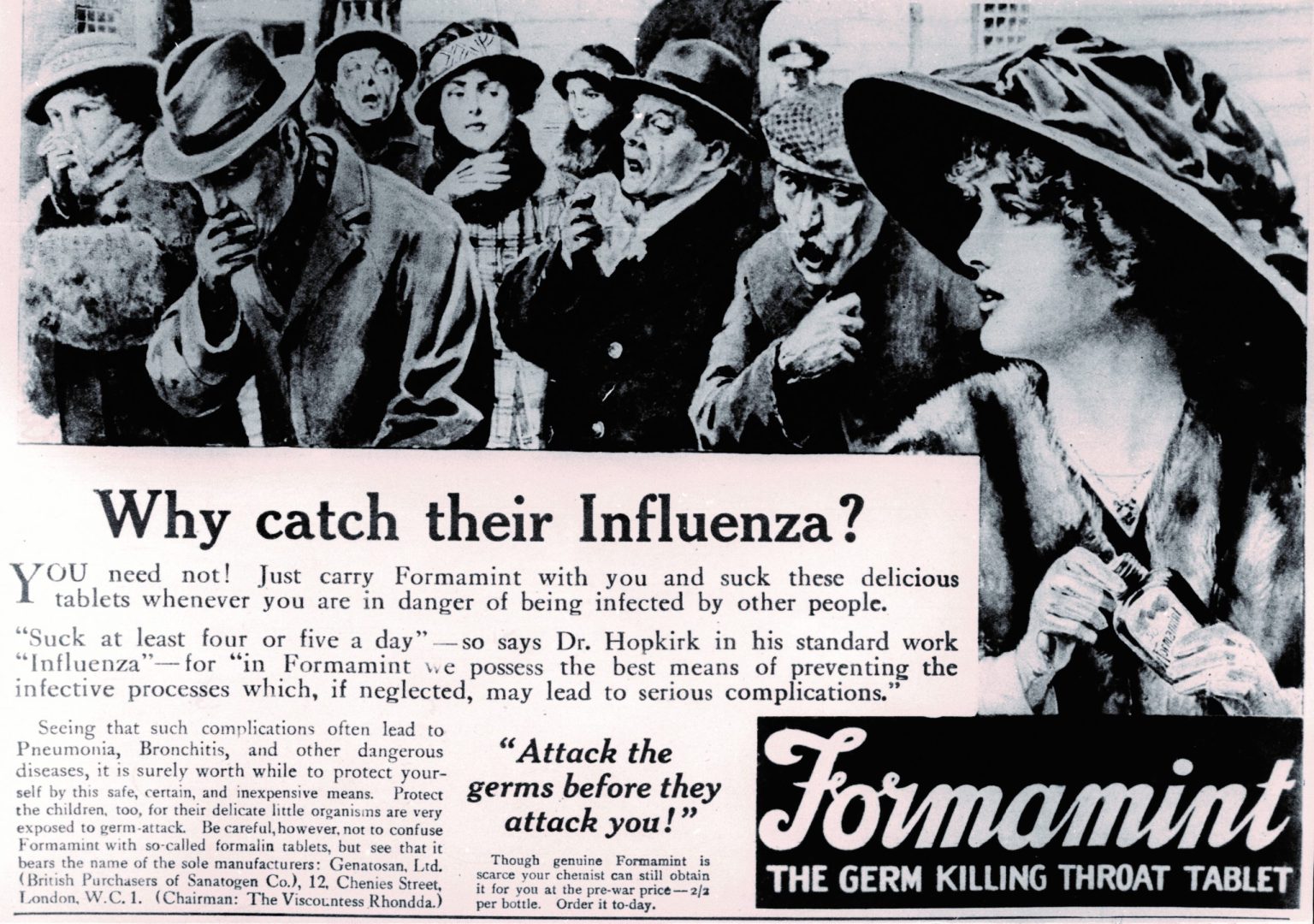

Fake news during this time was also a problem. Even as people were dying, there were attempts to make money by advertising fake cures to desperate victims. On June 28, 1918, a public notice appeared in the British papers advising people of the symptoms of the flu. It however turned out this was actually an advertisement for Formamints, a tablet made and sold by a vitamin company. The advert stated that the mints were the “best means of preventing the infective processes” and that everyone, including children, should suck four or five of these tablets a day until they felt better.

Fake news has been a concern since the outbreak of COVID-19, with the Internet making it even easier to spread it. See some of our fact checks on the subject here.

The deadliness of WW1 coupled with censorship of the press and poor record-keeping made tracking and reporting on the virus very tedious. This explains why the flu remains of interest to date as some questions are yet to be answered. In contrast, Media coverage on COVID-19 has been commendable and very useful to the public in providing much-needed answers.

Treatment/Vaccine

When the Spanish flu hit, medical technology and countermeasures were limited or non-existent at the time. No diagnostic tests or influenza vaccines existed. The federal government also lacked a centralized role in helping to plan and initiate interventions during the pandemic.

Many doctors prescribed medication that they felt would be effective in alleviating symptoms, including aspirin. Patients were advised to take up to 30 grams per day, a dose now known to be toxic. It is now believed that some of the deaths were actually caused or hastened by aspirin poisoning.

The first licensed flu vaccine appeared in America in the 1940s and from there on, manufacturers could routinely produce vaccines that would help control and prevent future pandemics.

Fast forward to 2020; clinical trials of COVID-19 treatments/vaccines are either ongoing or recruiting patients. The drugs being tested range from repurposed flu treatments to failed Ebola drugs, blood pressure drug (Losartan), an immunosuppressant (Actemra- an arthritis drug) and malaria treatments developed decades ago.

An antiviral drug called Favipiravir or Avigan, developed by Fujifilm Toyama Chemical in Japan is showing promising outcomes in treating at least mild to moderate cases of COVID-19.

As of now, doctors are using available drugs and health support systems such us ventilators to alleviate symptoms. There have been over 500,000 recoveries so far.

Doctors in China, South Korea, France and the U.S. have been using Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine on some patients with promising results. The FDA is organizing a formal clinical trial of the drug, which has already been approved for the treatment of malaria, lupus and rheumatoid arthritis.

Mistakes

The mistakes and delays in taking quick action we are experiencing today with COVID-19 are not new. In the summer of 1918, a second wave of the Spanish flu returned to the American shores as infected soldiers came back home. With no vaccine available, it was the responsibility of the local authorities to come up with plans to protect the public, at a time when they were under pressure to appear patriotic and with a censored media downplaying the disease’s spread.

Some bad decisions were made in the process. In Philadelphia for instance, the response came in too little too late. The then director of Public Health and Charities for the city, Dr Wilmer Krusen, insisted that the increasing fatalities were not the Spanish flu but the normal flu. This left 15,000 dead and another 200,000 sick. Only then did the city close down public places.

The End Of the Pandemic

The pandemic came to an end by the end of the summer of 1919. Those who were infected either died or developed immunity. The world has experienced other flu outbreaks since then but none as deadly as the Spanish flu.

The Asian flu (H2N2), first Identified in China from 1957-1958, killed around 2 million people worldwide. The Hong Kong (H3N2), first detected in Hong Kong, from 1968-1969, killed about 1 million people. Between 1997-2003, Bird flu (H5N1), first detected in Hong Kong, killed over 300 people. More recently in 2009-2010, the Swine flu (H1N1), which originated from Mexico, killed over 18,000 people.

The world’s population has increased from 1.8 billion to 7.7 billion since 1918. Animals alike, which are used for food, have also increased significantly, giving room for more hosts for novel flu viruses to infect people. Transport systems have gotten better making global movement of people and goods much easier and faster, further widening the spread of viruses to other geographical regions.

Even though considerable medical, technological and societal advancements have been made since 1918, the best defence against the current pandemic continues to be the development of vaccine or herd immunity. The biggest challenge, however, is the time required to manufacture a new vaccine. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC, it generally takes about 20 weeks to select and manufacture a new vaccine.

Dr Eddy Okoth Odari, a senior lecturer and researcher of Medical Virology in the Department of Medical Microbiology at the Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology breaks it down as follows:

“It is anticipated that “herd immunity” would protect the vulnerable groups. We must, however, appreciate that natural “herd immunity” may only occur when a sizeable number of the population gets infected. I note with concern that we may not know and should not gamble with the immunity or health of our populations. This would then call for an “induced herd immunity” through vaccination. Therefore as at now, we must increase our efforts in developing an effective vaccine.”

The World Health Organization (WHO) published instructions for countries to use in developing their own national pandemic plans, as well as a checklist for pandemic influenza risk and impact management. But even with all these plans, there are still loopholes that could still be devastating in the face of a pandemic, as we are currently witnessing.

Healthcare systems are getting overwhelmed and some hospitals and doctors are struggling to meet the demand from the number of patients requiring care. The manufacture and distribution of medications, products and life-saving medical equipment such as ventilators, masks and gloves have also significantly increased, seeing as there is already a shortage being experienced. Dr Okoth has a good explanation for this:

“Translation of research findings into proper policies has been slow since policy formulators have insisted on evidence. For example, as early as March 2019, publications had hinted into a possibility of a virus crossing over from bats to human populations in China, but unfortunately, there was no proper preparedness and if any, perhaps the magnitude of this potential infection was underestimated. Finally, the geopolitical wars and political inclinations among the superpowers are not helping much in the war against infectious diseases. When the pandemic started it was viewed as a Chinese problem, in fact, other nations insisted in it being called a “Chinese virus” or “Wuhan virus”. Even with clear evidence that the virus would spread outside China, the WHO (perhaps to appear neutral) insisted that China was containing the virus and delayed in declaring this a pandemic – the net result of this was that other countries became reluctant in upscaling their public health measures, yet other countries seem to have been keen not to be on the bad books of China.”

There is no telling how long the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic will go on for or when and how it will end, but global preparation for pandemics clearly still warrant improvement as Dr Okoth advises.

“Perhaps the lessons that we learn here is that diseases will not need permission to cross borders and since the world has become a global village, there should be proper investments in global health and scientific research.”

This article was originally published by Africa Uncensored. Graphics by Clement Kumalija.