Throughout African history, traditional birth attendants (TBAs) have provided maternity care for women despite having no formal training.

Poverty, cultural practices, and a shortage of primary healthcare services are forcing women to seek the help of untrained traditional birth attendants, despite the serious risks involved.

Last year Kenya recorded a maternal death rate of about 362 per 100,000 live births and an under-five death rate of 52 per 1,000 live births, while in Tanzania, one in every 126 women die due to maternity complications. The story is the same in Uganda and Ghana as well. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO)’s figures for 2016 on maternal mortality, 560 women die per 100,000 births in Nigeria.

Despite these shocking figures, women, even learned ones, are still flocking to unskilled birth attendants’ homes to give birth, putting their lives at risk. Why is this so? Is it is because governments are failing them?

For some women, traditions prevent them from attending hospital. For others, long distances to medical facilities prevent them from reaching a health facility in time to give birth. Some are put off by health workers’ attitudes.

TBAs can provide them with all the care they need, both during and after pregnancy and childbirth, and there is no doubt they are a much-needed resource.

In 2013, the Kenyan government introduced free maternal healthcare. The goal was to encourage more women to give birth in health facilities. However, according to data from the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) released this year, more women are still flocking to TBAs.

It is evident that pregnant women are not satisfied with the quality of care they are given at the hospitals. With the high number of women taking advantage of the free services, combined with the few health care workers to attend to them, some women are giving birth on their own even when they are in hospitals.

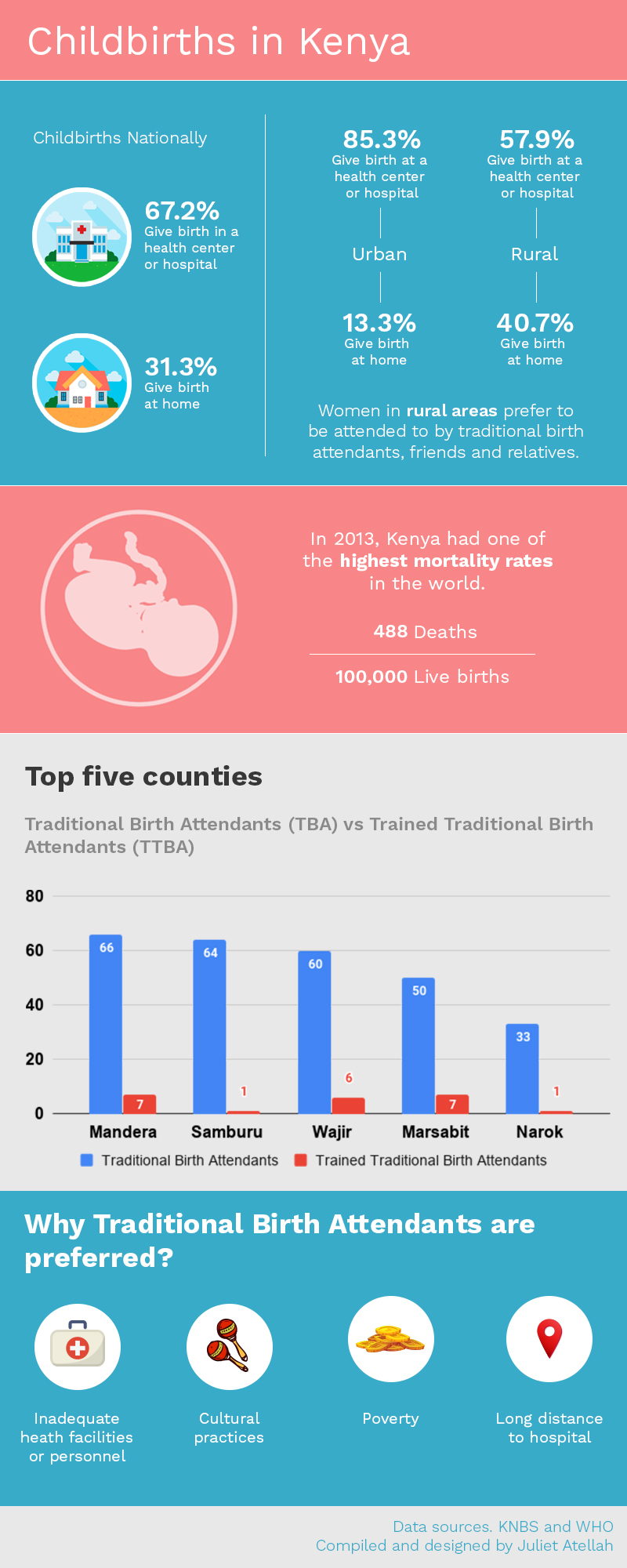

In 2013, Kenya had one of the highest maternal mortality rates in the world: 488 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births, according to the Ministry of Health.

In 2013, the Kenyan government introduced free maternal healthcare. The goal was to encourage more women to give birth in health facilities. However, according to data from the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) released this year, more women are still flocking to TBAs.

According to KNBS data for 2015/2016, the findings reveal that three out of ten children were delivered at home in 2018 in Kenya; this is an estimated 31.3 per cent improvement from 53.9 per cent recorded in 2005/06.

The survey showed that in rural areas the proportion of children born at home was 40.7 per cent compared to 13.3 per cent in urban areas.

“The county with the lowest proportion of children born at home was Kirinyaga, at 3.8 per cent, while Wajir, Mandera, Samburu and Marsabit had over 70 per cent of children born at home. Kirinyaga, Nyeri and Kisii counties recorded over 90 per cent of children born in a health facility,” KNBS stated.

The proportion of children delivered with the assistance of a traditional birth attendant in rural areas was 25.6 per cent compared to 7.8 per cent in urban areas. Wajir, Mandera and Samburu had over 60 per cent of the births assisted by a traditional birth attendant. Turkana County had the highest proportion of self-assisted births, at 34.5 per cent.

The low hospital births among pastoral communities may be partly linked to inadequate health facilities and personnel in the regions they live in. Families in pastoral counties also tend to be polygamous, which puts a strain on resources such as healthcare.

Nairobi, Kisii, Kiambu, Kirinyaga and Nyeri counties top in childbirths in hospitals, an indication of the success of the safety campaigns. These five counties are the only counties that recorded over 74 per cent of children born in hospitals.

Statistics further show that more deliveries are now handled by trained medical personnel, which is a plus in attaining safer childbirths. However, women in rural areas still prefer to be attended by TBAs, friends, and relatives during delivery.

According to WHO, with the exception of sub-Saharan Africa, where most births in rural areas are conducted by TBAs, rates of births assisted by a medically trained attendant have shown impressive increases over the past 15 to 20 years, Current data indicate that 59 per cent of births in the developing world are assisted by a medically trained professional.

Nairobi, Kisii, Kiambu, Kirinyaga and Nyeri counties top in childbirths in hospitals, an indication of the success of the safety campaigns. These five counties are the only counties that recorded over 74 per cent of children born in hospitals.

Uganda banned TBAs) in 2010 but they have continued to practise. Eighty per cent of rural women prefer TBAs to skilled attendants, according to officials at the Ministry of Health; 10 per cent of them delivered with the assistance of TBAs.

With TBAs playing such an important role in maternal and newborn healthcare, especially in rural areas, should governments abolish them completely or look for ways of incorporating them into the system as referral agents to hospitals?

One midwife’s experience

The Telegraph, through an informal survey in Kisumu’s Nyalenda Estate in Kenya, established that some mothers delivering in hospitals still relied on traditional birth companions during pregnancy and after giving birth.

Pictures of newborn babies adorn the walls of Margret Owino’s house. They are a treasured decor in the improvised maternity ward in her two-roomed corrugated iron-walled house. Hundreds of women have trekked the dusty and curvy road to Ms Owino’s Kisumu home, judging from the many pictures.

It is at 6 am when we got to her house. Dressed in a blue nylon apron, she is busy attending to a pregnant woman. In a busy month, she delivers over 60 children, according to her well-kept records.

Her small house acts as a labour and delivery room. She is among traditional midwives who assist women at childbirth, mostly in areas that lack infrastructure and trained health personnel.

Even though there are several health facilities in the area, some pregnant women prefer traditional birth attendants. They say they are more comfortable with them than obstetricians and trained midwives.

Ms Owino learned the midwife’s skills at a tender age. When she was 15 her late grandmother, who was a midwife, placed herbs in her right hand and some coins in the left — the traditional way of transferring the skills to her. This has since been her job. She is among Kenya’s 35 registered traditional birth attendants who work with hospitals to ensure safe deliveries.

She has had women who are bleeding profusely brought to her in the middle of the night. She does not attend to them but sends them immediately to the nearby hospital. Some clinics contact her to attend to mothers with breech births and at times they are brought to her “clinic”.

She also refers HIV-positive women to the hospital, but says she knows not all women disclose their status to her. She says it is a constant risk.

Her maternity services are similar to those in health facilities. She records clients’ details in a book and weighs infants on a weighing machine given to her as a token.

One of her clients said that harassment in public hospitals is one of the reasons they still troop to traditional birth attendants’ clinics.

Even though there are several health facilities in the area, some pregnant women prefer traditional birth attendants. They say they are more comfortable with them than obstetricians and trained midwives.

‘‘The midwives harass us, calling us names while we are often left in the hands of inexperienced trainees. The midwife can detect when a woman has the strength to push the baby or not, or if the baby is in the right position,” she says.

She says community midwives pamper and take care of women during and after delivery. She says this helps them give birth with dignity. That is why a lot of women come back to her when they are having another baby

Initially, the government was threatening the TBAs while others were being harassed and their tools were being confiscated. However, this has since changed; they are now being registered and undergo training to ensure safe deliveries.

The Ugandan government has also lifted the ban on TBAs and the focus now is training them. As a result, there has been a shift towards skilled birth attendants capable of averting and managing childbirth complications.

Ms Owino only attends to women who know their HIV status. She ensures that HIV positive clients have antiretroviral (ARVs) drugs given by a doctor, which she gives to the child immediately after tying the umbilical cord.

Benefits of supporting and training TBAs

Rather than educate against the use of TBAs, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) believes that working with them is the best solution. It did a a study on the benefits of supporting and training TBAs across the world. The study was done in the Upper East Region in Ghana, and tracked antenatal visits and deliveries conducted by trained TBAs from 1990 to 1993.

“Antenatal visits increased from 20,000 to 180,000. Deliveries reported by TBAs increased from less than 10,000 to 50,000. Nationally, the percentage of TBA deliveries as a percentage of supervised deliveries increased from 16.4 percent to 22.2 percent between 1992 and 1993. Policymakers and program managers state that TBAs have contributed to: improve prenatal care, increase contraceptive acceptance rate, and decrease neonatal tetanus admissions”.

“The role of traditional birth attendants in the provision of healthcare in resource-poor countries is still important because of the current inadequacy of human resources for health. In developing countries for years to come, TBAs will remain the main providers of child deliveries in rural areas,” it states.

Dr Elizabeth Ogaja, a health analyst, says that midwives are an integral part of the healthcare system, adding that the reduction of maternal and newborn mortality in developing countries requires rigorous efforts that involve governments and non-governmental organisations in identifying TBAs who are known by the community to be experts.

“Recruitment and training of TBAs using adult learning techniques is important. The programmes should focus on basic primary healthcare, especially on symptoms of risky cases that need to be referred to formal health services and on hygiene to prevent mother and child from infections,” she says.

“Creation of dialogue, trustworthiness, patient, tolerance, willingness to collaborate, transparent and familiarity during training are key when working with TBAs as partners in health care and when sharing experiences,” says Dr Ogaja.

Training, she says, should be followed up by frequent meetings to share feedback and problems TBAs experience.

“We have realised that they are very important. Mothers trust them and we want to integrate them as much as we can. We advise that they bring pregnant mothers to hospitals so that we can take it from there,” she says.

Dr Lawrence Koteng’, the Homa Bay health executive, acknowledges the role played by traditional midwives but encourages expectant women to deliver in health facilities.

He says the county health department is training community health workers to discourage unsafe home deliveries.

“We do not support expectant women to deliver at home or anywhere except at health facilities where there are experts who can help whenever there is a complication,” says Dr Koteng’.

However, Allan Mayi, the deputy project director at Elizabeth Glaser Paediatric Aids Foundation, says the birth attendants should not attend to expectant mothers because they lack the skills needed to offer safe deliveries.

The organisation encourages women to deliver in hospitals and even offers incentives to birth attendants to take them to health facilities.

“Most mother-to-child HIV transmissions are recorded at midwives’ homes,” says Mr Mayi.