The right to food as stipulated in Article 43 of the Constitution of Kenya recognises that all Kenyans have the right to be free from hunger and to have adequate food of acceptable quality. But we are still hungry.

Kenya has had several droughts that have affected its productivity yields in agriculture over the past few years. This, in tandem with corruption, inefficiency and demographic bulge has put pressure on our current food systems. Food prices have therefore increased to the detriment of the consumer whose income has barely increased.

Because of this, it is estimated that about 16 million Kenyan’s are poor, 7.5million people live in extreme poverty, and over 10 million people suffer from chronic food insecurity and poor nutrition. During periods of drought, heavy rains and/or floods, the number of people in need could double if this trend continues.

Since 2007, the cost and volatility of many staple food commodities (maize flour, beans, carrot and milk) have increased tremendously. Adverse weather conditions and climate change, prolonged or recurrent droughts, shifts in local production, disease and consumption shocks, inflation and changing informal trading patterns, are rapidly redefining food affordability and transforming food consumption, production and market dynamics.

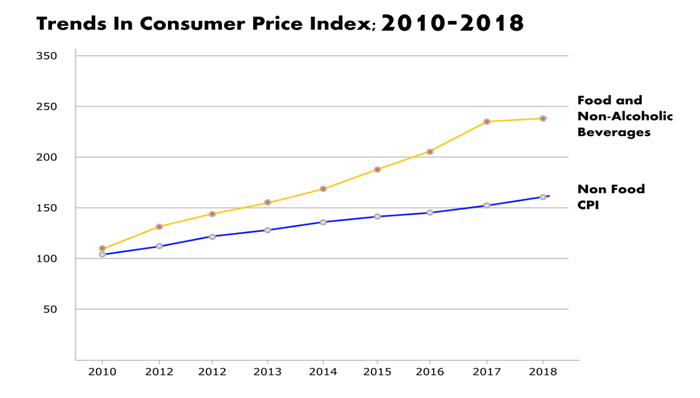

The Consumer Price Index – a measure of prices of a basket of goods over time – has also increased since 2007 due to a steady increase in prices of food and non-alcoholic drinks. While the annual average of non-food Consumer Price Index (CPI) which includes alcoholic beverages, tobacco, narcotics, clothing, footwear, housing, water, electricity, gas and other fuels, furnishings, household equipment and routine household maintenance, health, transport, communication, recreation & culture, education, restaurant and hotels and miscellaneous goods and services, has increased by 53.9 per cent.

Retail prices of food products have gone up by 83.3 per cent in the last ten years. During this time, 30 per cent of food commodities have tripled in prices. The prices of kerosene and petrol rose by only 15.73 and 28.23 per cent respectively over the same period. The slow rise in the fuel prices was mainly due to the decline in international oil prices that started in 2014 through to 2018. Government revenue and expenditure increased over the past years though expenditure grew at a faster pace resulting in the increase of fiscal deficit.

Retail prices of food products have gone up by 83.3 per cent in the last ten years. During this time, 30 per cent of food commodities have tripled in prices. The prices of kerosene and petrol rose by only 15.73 and 28.23 per cent respectively over the same period. The slow rise in the fuel prices was mainly due to the decline in international oil prices that started in 2014 through to 2018. Government revenue and expenditure increased over the past years though expenditure grew at a faster pace resulting in the increase of fiscal deficit.

Household spending

Data from Basic Report Based on 2015/16 Kenya Integrated Household Budget Survey, shows the majority of households spend 44.6 per cent of their budget on education. Food closely follows at 33.5 per cent. In male-headed households, expenditure on education accounted for more than half of the cash transfers while female-headed households spend a higher proportion on food. Nationally, 54.7 per cent of cash transfers received from government programmes was spent on education while 32 per cent was spent on food. In rural areas, 43.8 per cent of cash received was spent on education compared with 73.4 per cent in urban areas.

Shocks to Household Welfare

A shock is an event that may trigger a decline in the well-being of an individual, a community, a region, or even a nation. According to the economic survey (2017) the shocks which occurred during the five-year period preceding the survey and had a negative impact on households’ economic status/welfare.

Three in every five households reported having experienced at least one shock within the five years preceding the survey. A sharp rise in food prices was reported by the highest proportion (30.15%) of households as the first severe shock. Most households reported that they used their savings to cope with the shock(s).

The severity of a shock is assessed to define the impact on the household’s economic or social welfare. This is a simple ranking mechanism from the respondent’s perception to assist in determining the effect of the shock. A severe shock has debilitating effect on the household economic or welfare status.

Nationally, a steep rise in food prices was reported as a severe shock by the highest proportion of households (30.1%). Other shocks reported by households as severe were droughts/floods (27.3%), death of other members of the family (21.5%) and death of livestock (20.1%).

In urban areas, high proportions of households reported that they struggled with high food prices (18.6%) and the death of other family members (14.9%). Death of other family members was ranked as the first severe shock, by about the same proportion of households in rural and urban areas. Households that lost livestock through death or theft mainly resorted to selling animals, while those affected by high food prices reduced food consumption at the household level.

According to the derived poverty lines, households whose adult equivalent food consumption expenditure per person per month fell below Ksh 1,954 in rural areas and Ksh 2,551 in urban areas were deemed to be food poor. Similarly, households whose overall consumption expenditure fell below Ksh 3,252 and Ksh 5,995 in rural and urban areas, respectively, per person per month were considered to be overall poor. Further, all those households that could not afford to meet their basic food requirements with all their total expenditure (food and non-food) were deemed to be hard-core/ extreme poor.

Rising food prices in Kenya have an adverse effect on the country’s development as a whole. Key contributors, partners and relevant authorities in the food sector should continue to analyse food prices and related issues, put in place mechanisms to respond to early warning of disasters such as droughts, floods and other disasters and come up with strategies to avert the negative effects of high food prices in the future.

Written and published with the support of the Route to Food Initiative (RTFI) (www.routetofood.org). Views expressed in the article are not necessarily those of the RTFI.