Maureen was in labour when it happened. The stern nurse needed an answer, but she was in too much pain to think. Her body and mind were fighting each other by that point. Twenty-two years old and lying on a stretcher outside the theatre at Kakamega Hospital, she had never felt more alone. And the nurse wouldn’t let her be wheeled in until she signed the bloody forms.

“I can see in your file that you are HIV positive,” the nurse said again, unmoved, “You must have tubal ligation since HIV positive women are not supposed to give birth.” So she took the pen and signed, and then zoned out. When she came to, she was a mother. A few hours later, the child was dead. In her pain, she had signed away her right to ever have another baby.

That was in 2005.

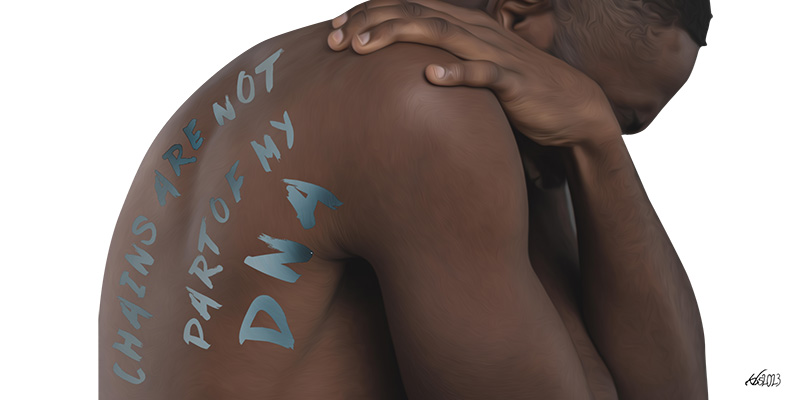

Forced sterilizations of HIV-positive pregnant women first came to light in 2012, although it had been happening for decades. The report, Robbed of Choice, carries multiple stories like Maureen’s. Almost all the cases documented were of poor women in public hospitals and non-governmental clinics. It was our modern form of eugenics informing unofficial policy with real consequences; an attempt to clean up the gene pool by getting rid of those we deem unfit, or at least take away their right to reproduce.

Derived from Darwin’s theories and given its modern name by Darwin’s cousin, Francis Galton, in the 19th century, eugenics is more about class than race. Although the concept preceded that era, it gained a new, organised lifeline that only began ending in the late 1930s. In its origins it was about getting rid of the undesirables, not just based entirely on skin colour, but also on socioeconomic status. Among its pioneers was Frederick Osborn who viewed eugenics as a social philosophy deserving of some form of proactive action. To actively do this in politically sensitive times required tact, such as deliberately under-developing certain areas, refusing to invest in education and healthcare, and sometimes undertaking outright sterilization. Although it never gained mainstream government approval as the governing philosophy in the colonies, it influenced and provided propaganda for many racially-driven policies.

It was a eugenics organization where scientific racism would thrive, designed to prove that blacks were inferior.

In the utopia the colonial project envisioned, Kenyans would always be at the bottom of the social pyramid, with whites at the very top, and Asians in the middle as a buffer. But because Kenya attracted the British aristocracy, the class element was also important to the immigration policy regarding poor whites who were seen as undesirable. With hordes of eugenicists driving the colonial project, their ideas on class and social control infused themselves into the colonies in such core ways that they never left.

In July 1933, 60 white men and women gathered in a boardroom at the New Stanley Hotel in Nairobi. Among them were medical doctors, executives, government officials, journalists, scientists and other prominent white people. There were also a few Indians in the room. Their common goal was to formalize a eugenics group that ended up with the lengthy name Kenya Society for the Study of Race Improvement (KSSRI).

Of the 60 people in that room, two emerged as the mouthpieces of the group. Henry Gordon and Dr FW Vint were both medical doctors who tried to use science to prove that whites are superior by nature. This was already at the core of the eugenics movement, but in Kenya it was only one part of the core structures of colonialism, which were built on the similar concept of “the white man’s burden”. Gordon was in charge of Mathari Mental Hospital, the only mental health institution in the country at the time. Even within the institution—established in 1910 as the Lunatic Asylum—access to facilities had always been segregated on the basis of race. Kenyans occupied the worst facilities in the 675-bed hospital, and Europeans the best. Up until the 1960s, all the members of the medical staff were European.

One of the main motivations behind the formation of the KSSRI was the growing clamour for better education for Kenyans.

While the group included people from many backgrounds and professions, it was medical science that provided it with the most potent propaganda; the group’s vice chairman was Dr James Sequeira, who was also the editor of the influential East African Medical Journal. The dominance of medical science and pseudo-science in Kenya’s eugenics movement was a result of the growth of British medical care in Kenya in the 1920s, as white doctors became essential to keeping Africans healthy so they could work for settlers and pay taxes.

In Race and Empire: Eugenics in Colonial Kenya, Chloe Campbell explores how Gordon and Vint used science to try and prove that Kenyans did not possess sufficient innate mental capacity and hence should not be educated at the same level as their European colonizers. In one study, Gordon studied 219 Kenyan boys housed at the Kabete Reformatory. He concluded that 86 per cent suffered mental conditions, but even the rest couldn’t be considered okay without creating several grades of “European ideas of normality”.

In another study, Gordon tested 278 Kenyans—112 of whom had already been diagnosed with mental illness—for the venereal disease syphilis. When he found that more than half the group with mental conditions suffered from the disease, he concluded that it was the racial differences, and not the social and economic differences in the new colony, that caused the disparity.

This particular argument was not new; in a 1905 book, a settler had blamed Indians and Swahilis for the rise of venereal diseases in Kenya. He’d offered that “the healthiness of a place is greatly increased by not allowing any native habitations within a given distance of the white settlement”.

As a government pathologist, Vint focused his studies on correlating skull size with intelligence. He studied 100 skulls and arrived at the conclusion that Kenyans had lighter skulls and smaller pyramidal cells. In 1934, he concluded that Kenyan brains could not grow past the age of 18 years, and that they started decreasing in size after that. That was the same year primary education became mandatory for white children, while investments in the education of African children remained paltry. Vint’s work was meant to prove that there was no need of educating Kenyans because they did not have the capacity to grasp complex concepts.

After Gordon wrote about some of their findings in The Times, Louis Leakey responded with a letter attacking their methods and their conclusions, but not their premise. Instead, the Kenyan-born anthropologist argued, the feeble mindedness of the “African mind” should be attributed to “the lack of stimulation in the normal conditions of African life and to the fact that sexual activity began at a younger age, somehow inhibiting mental development,” Campbell writes.

Beyond the pre-existing issues with race, there had been another more immediate reason for the formation of the KSSRI in 1933. Just a few months before, the colonial government had hanged a 19-year-old white man, Charles William Ross, for the brutal murders of two young white women. Ross, who was born in Kenya, had killed the two women, thrown one body in the Menengai crater, and left the other at the top. As part of Ross’s defence, Gordon used an X-ray photograph of Ross’s skull to assert that he was criminally-liable because of “pronounced mental instability” that placed him somewhere between “feeble-minded” and “moral-deficient.” He was found guilty anyway, and hanged on 11 January 1933.

This were the same explanations Gordon and other psychiatrists applied to the entirety of the black Kenyan population, more so when they were involved in crime.

With the economic depression of the 1920s and the increasing education of Kenyans, crime rates had shot up in urban areas. Juvenile delinquency was of particular interest, and Gordon would go on to claim that the majority among his subjects in the study at Kabete had some education. The point was that they had been overwhelmed by British education. This was the “feeble-minded” argument, which also drove racially-motivated policies in the economy, healthcare and other facets of life, including the justice system. From the outset, the colonial system had set to educate Kenyans to be church-going technical workers and manual labourers, not free-thinking intellectuals.

The parliamentary discussion on the law that made sexual assault a capital offense laboured on whether it should be applied to non-Kenyans as well.

Interestingly, eugenicists also considered urbanisation to be one of the reasons for the increase in crime and psychiatric cases. In their thinking, urbanisation “detribalised the African and made him unmanageable”. It was part of the thinking that the African mind simply couldn’t handle too much change because it was not genetically wired to do so. Change destabilised their feeble minds and led them to crazy thoughts that they could ever upend the social pyramid. This thinking preceded and survived the official eugenics movement in Kenya which lasted from 1930 to 1937.

On the Christmas Eve of 1911, for example, the Machakos district commissioner wrote a lengthy report on “the mania of 1911”. It was the story of Siotune Kathuke and Kiamba Mutuaovio, who had led several acts of rebellion. Their sermons had supposedly inspired a widespread mania, as more people began to question the ordained order of things. Another good example is the commitment of Elijah Masinde, the founder of Dini ya Msambwa, in 1945. He was committed at Mathari for pretty much the same reasons that Siotune and Kiamba were exiled to the coast. When he was released in 1947, Masinde promptly went back to preaching the end of white rule.

Campbell notes that although the government didn’t fund the eugenicists’ work or officially base its policies on their work, it showed its support in other ways. One was the continued underdevelopment of Kenyans, and the other was more subtle, like giving Gordon a three-month leave from his work to go and try to win support from other eugenicists in London. The members of the KSSRI were also well connected; shortly after they founded the organisation, a group of them went to a ball held at Government House (now State House), which is the opening scene in Campbell’s book. But the movement could not have chosen a worse time to try to push for eugenics, as Hitler’s Nazi Germany employed similar ideas to devastating effects. Thus, the prominence of eugenicists in Britain and in colonies like Kenya diminished in the late 1930s for political reasons, but the ideas survived.

Another prominent figure in the pseudo-science of “African intelligence” was a retired doctor called JC Carothers, who succeeded Gordon at Mathari. He had submitted a widely-read paper on African intelligence to the World Health Organization when the colonial government turned to him to write what became “The Psychology of the Mau Mau”. Published in 1954, the report shows a slight change in the racist perspective regarding African intelligence. Where Gordon had focused on biology alone, Carothers expanded his scope to include environmental issues.

In resisting a common electoral roll, settlers argued that it was unfair to be forced to wait for Kenyans to catch up on the civilisation scale.

Turning his focus to the Kikuyu, who made up the majority of the Mau Mau ranks, Carothers thought that since the Kikuyu had had greater contact with their colonizers, “Kikuyu men have envied this power, not unnaturally, and have tried to capture it by learning.” Kikuyu women were not part of this because Carothers thought that “Her life … has suffered little change,” that her focus was still on agriculture and child-bearing, meaning she had lost her men who “have found themselves with money and powers which have virtually turned their heads. Power has come quickly to folk who are not … familiar with it”. These were Gordon’s ideas, with a dash of flair and some added flavour.

Louis Leakey was another instrumental scientist in that decade, helping counter-insurgency efforts in many ways. His best known effort was on oathing, arguing that the Mau Mau was led by brilliant psychopaths who had changed the oath’s meaning and even particulars. His counter-insurgency research and work may have actually escalated the war in 1952, which was one of his goals. Leakey thought that if he made the problem big enough, then it could be quickly addressed. He used his personal and anthropological knowledge of Kikuyu culture to devise a counter-oath that would free those who had taken the Mau Mau oath, and was core to the psychological counter-insurgency.

While eugenics concepts did not directly shape policy, they formed a part of the larger racist ideologies that informed many laws of the colonial era, a good number of which survive to date. They were notoriously anti-poor and anti-Kenyan, offering tokenism and hiding behind legalese. The Witchcraft Act, for example, banned many cultural practices by purporting to regulate them. It even made it an offence to pretend to be a witchdoctor.

After independence, the power and social dynamics espoused by racism switched back to class their roots, this time driven by a black, mostly Western-educated elite. The White Highlands went to a new class of supremacists, who quickly passed the Vagrancy Act in 1968. Under this law, you could be arrested and placed in a rehabilitation home if you were found walking in a posh estate with no money in your pocket and no known source of income. The Act had existed as the Vagrancy Regulations in the colonial system, only to be formalized when Kenyan elites started replacing settlers. Perhaps unsurprisingly, it survived in our laws until it was repealed in 1997.

Using the lessons learned during the decade of the Mau Mau war, the new government launched a similar counter-insurgency against a secessionist movement in Northern Kenya. The model of brutality, concentration camps and spirited propaganda fit in the ’60s as it had in the ’50s, with added efficiency.

Combined with other laws and institutions such as the police, the colonial view of the base of the pyramid survives. It is why the introduction of free primary education and maternity healthcare as public goods was such a big deal. Pro-poor policies have surprisingly been few in independent Kenya as an African elite only sought to replace, not displace, the colonial order. The paternalistic relationship between the individual and the state is still intact, as becomes clear whenever there is an internal threat to social order.

The forced sterilizations report points to how institutionalised eugenics survives. They were happening with tacit government approval, and targeted a class of “undesirables”. The sterilizations probably thrived in the first decade of HIV/AIDS in Kenya when there was official and social denial of the extent of the problem. We might never know their true extent, although a few of the institutions named in the report should not come as a surprise.

Pro-poor policies have surprisingly been few in independent Kenya as an African elite only sought to replace, not displace, the colonial order.

One is Marie Stopes International, named for British author Marie Stopes. While Stopes is today regarded as a feminist pioneer, the major driving aspect of her birth-control advocacy was eugenics and not women’s rights. Her ideas about the poor are particularly worrying, as that is whom her clinics targeted from the onset. She was a lifelong eugenicist, who even disinherited her son Harry because he married a short-sighted woman. The other institutions named in the report—government hospitals—are still wallowing in under-investment and neglect.

Infused in post-colonial Kenya was not eugenics as a concept, but as a form of social control. It is many other things now by many other names, but it seems focused on further impoverishing those who are already poor while enriching those already endowed. A few might cross that socioeconomic divide, but many never will.