Tawa wa Kahara

Cege Rehe itete

Hihi ini nĩ rĩhĩu

Moko ma komo

To some Kenyans, the above verse is pure gibberish. However, to others, myself included, the first line alone is enough for lips to remember the words as the mind embarks on a journey into the past, back to childhood, unearthing vivid memories of where they were, when and how they learnt to sing them. So much so that eyes begin to water.

Seventy-one years after it was first published, that verse now encapsulates a place, a year and a time in Kenya’s history. It has also become a badge of honour for many seeking to reclaim their pride in their culture, identity and language.

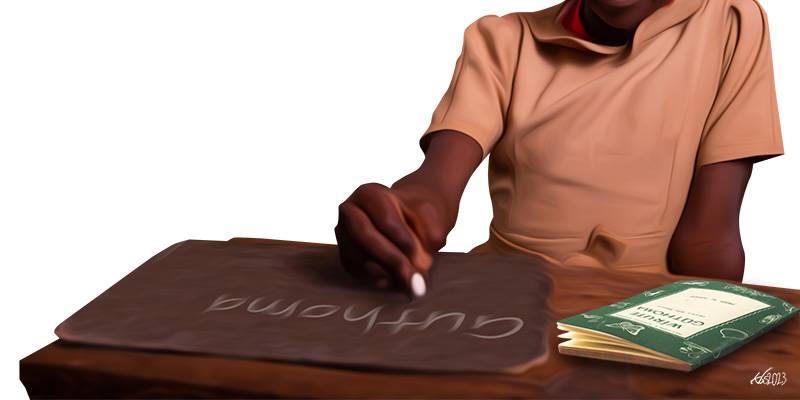

It is a verse in a Gĩkũyũ alphabet rhyme that appears on page 11 of the now famous book, Wĩrute Gũthoma – Ibuku Rĩa Mbere (Learn to Read – Book 1) by Fred K. Kago. Published in May 1952 by the now defunct Nelson‘s Kikuyu Readers, it was one in a series of three books that became the first ever of their kind to be written entirely by an African teacher for the learning and teaching of an indigenous African language in the school curriculum.

For years now, Kago has continued to both confound and arouse a great curiosity in many Kenyans. A dearth of his beloved series, which went out of print a decade ago, has left many searching online. There are inquiries on social media platforms about where one might procure copies, even as others post content from the books to either reminisce or demonstrate a sense of pride in having learnt their mother tongue in school.

Yet a search online will turn up his work but nothing about who he was, what he looked like, where he grew up, where he was educated, what kind of person he was, what drove him to write textbooks for teaching indigenous African languages in the late 40s. More importantly, there is little to tell the story of his profound impact, which went well beyond the teaching and learning of African languages in schools.

Kago’s Wĩrute Gũthoma series has had a profound effect on my life, not just as a native of the culture but also, and more significantly, on my work as a Gĩkũyũ digital language advocate and a poet who writes and performs in her mother tongue.

The complex history of indigenous languages in Kenya’s education system

The role of the mother tongue, Kiswahili and English in the domain of education in Kenya was first discussed during the United Missionary Conference in Kenya in 1909. The conference then adopted the use of the mother tongue in the first three classes in primary school, Kiswahili in two of the middle classes, while English was to be used in the rest of the classes up to university.

Since then, during and after the colonial period, some key commissions were set up to review education, including the Phelps-Stokes Commission of 1924. Some of these endeavours had a bearing on language policy. In his paper Language Policy in Kenya: Negotiation with Hegemony published in The Journal of Pan African Studies, 2009, W. Nabea writes:

The colonial language policy was always inchoate and vacillating such that there were occasions that measures were put in place to promote or deter its learning. However, such denial inadvertently provided a stimulus for Kenyans to learn English considering that they had already taken cognizant of the fact that it was the launching pad for white collar jobs.

The freedom struggle after the Second World War, however, prompted a paradigm shift in the colonial language policy that hurt local languages. This shift began as the British colonialists started a campaign to create a Westernized, educated elite in Kenya as self-rule became imminent. Thus, English was reintroduced in lower primary and taught alongside the mother tongue. Kiswahili started being eliminated from the school curriculum.

Kago wrote the manuscript of what became the Wĩrute Gũthoma series in the late ‘40s while Kenya was still a British colony and more than a decade away from gaining its independence. At the time, command of the English language was considered the badge of the educated and civilized native and African indigenous languages were fast being shunned in schools as many began seeking education. They were regarded as second-class languages and the hallmark of how primitive people spoke. Kago was clearly swimming against some heavy currents.

The freedom struggle after the Second World War, however, prompted a paradigm shift in the colonial language policy that hurt local languages.

However, for children who grew up in rural Kenya in the 60s, 70s and 80s, learning indigenous African languages in the early years of primary education (from nursery until grade 3) was mandatory. For them, Kago became synonymous with that experience. However, the use of indigenous African languages in the early years of primary education has had a complex history.

Since the United Missionary Conference in Kenya of 1909, the decision to include or remove the teaching of Indigenous African language in the language policy was either at the whim of the political climate at the time or based on the interests of the missionaries.

Kago joined government service in 1931 as the Phelps Stoke Commission of 1924, which advocated for both quantitative and qualitative improvement of African education, was well into its implementation. According to the academic paper titled The Treatment of Indigenous Languages in Kenya’s Pre- and Post-independent Education Commissions and in the Constitution of 2010, the commission recommended that,

The languages of instruction should be the native language in early primary classes, while English was to be taught from upper primary up to the university. Schools were urged to make all possible provisions for instruction in the native language. However, the Commission recommended that Kiswahili be dropped in the education curriculum, except in areas where it was the first language. Kiswahili’s elimination from the curriculum was partly aimed at forestalling its growth and spread, on which Kenyans freedom struggle was coalescing.

Throughout Jomo Kenyatta’s reign and well beyond Daniel Arap Moi’s presidency, the post-colonial commissions such as Gachathi (1976), Koech (1999) and Odhiambo (2012) all recommended that a child should be taught using the pre-dominant language in the school catchment area and Kiswahili should be used only in schools with a heterogeneous school population. The supremacy of English in the Kenyan educational system entrenched by the Gachathi Commission of 1976 continued even as Kiswahili and indigenous languages received inferior status in the school curriculum.

The Wĩrute Gũthoma series was translated widely and used by the Kenya Institute of Curriculum Development in teaching other African languages. He had a virtual monopoly on the market in the colonial and immediate post-colonial periods.

Who was Fred K. Kago?

For a man whose books have nurtured more than four generations of learners, and one who has made immense contributions to the development of the post-independence school curriculum—including the setting up of numerous training colleges and developing their teaching materials— very little is known of Kago.

Until his demise in July 2005 at the age of 92, Kago was both a polymath and an outlier. He was a footballer, a bugle player (horn played during boy scout troop meetings), an organist, a piano player, a writer, a hospital administrator, a talented teacher and a scholar. Fondly known to his friends and relatives simply as F.K., the late Fred Karanja Kago was born in Thogoto village, Kikuyu Division, Kiambu District in 1913. He was the first-born child of Kago wa Gathatu and Eva Murugi.

He had a virtual monopoly on the market in the colonial and immediate post-colonial periods.

Kago grew up in a typical Kikuyu traditional homestead at a time when education was not really a priority for many families. It was by pure luck that he started attending school in 1920 as his parents viewed education as a disruption to the roles traditionally assigned to young boys—primarily grazing their father’s sheep and goats. Kago only became enrolled after his half-sister Wambui died following the 1918 Spanish flu epidemic (Kĩmiiri). Back then, the missionaries required that each homestead send one child to school. Kago became her replacement because he was quite small for his age compared to his younger brothers who were much bigger and much stronger workers on the family land.

Described as a reluctant schoolboy in the November 1986 edition of The Weekly Review Magazine, it is Kago’s who took him to the mission school every day. As a child, Kago was innately bright and had a curious mind, excelling in anything he took an interest in. As soon as he settled down to school life, Kago was excelling in football, and in the boy scout brigade where he became the designated bugle player to mark key moments during troop meetings.

In March 1926, Kago was admitted to the newly established Alliance High School. As reported in his eulogy, Kago’s only other classmate was the late James Mbotela (father to Leonard Mambo Mbotela). While at Alliance, Kago joined the newly formed first African Boy Scouts troop where he soon became the Senior Troop Leader. He also learned how to play the organ.

At the end of 1931, having passed the final government school examination, and with no money to send him abroad for further education, Kago taught briefly at Alliance and then joined government service.

He was posted to the Veterinary Training Centre at Ngong where he taught for thirteen and a half years before joining Waithaka Junior Secondary (later renamed Dagoretti High School) in 1944 as principal for the next three years.

It was, however, three government scholarships and the ensuing promotions that were to mark a turning point in Kago’s life from a teacher and trainer to a prolific writer.

Kago the pioneering author in indigenous African languages

Kago pioneered the writing and publishing of books in indigenous African languages. He authored numerous books—over 30 titles—that were published not just in his native language but also in English, Kiswahili, Dholuo and Kikamba. Besides the Wĩrute Gũthoma series and its respective teachers’ guides (translated into Kiswahili, Kikamba and Dholuo), Kago also wrote The Teaching of indigenous African languages – A Handbook for Kikuyu Teachers; Ciumbe cia Ngai (God’s creation); Hadithi za Konga Books 1,2 and 3; Mango’s Grass House; Lucky Mtende; and The King’s Daughter. Kago also adapted and had the Longman’s (now Longhorn) Shona Readers Books 1 and 2 translated into Kikamba, Kikuyu, Dholuo and Kiswahili and the Highway Arithmetic textbook and The Three Giants storybook into Kikuyu.

The start of Kago’s journey into writing was purely experimental. It was while attending the University of London’s institute of education in 1947 to study for a teaching diploma on a government scholarship that Kago decided to try his hand at writing textbooks for primary schools.

Growing up, Kago had learnt traditional Kikuyu stories, riddles and songs at his father’s feet, learning the richness of his language through the expression of idioms, proverbs, riddles and phrases. As an educator, he had witnessed first-hand the dearth of textbooks in African indigenous languages.

Kago pioneered the writing and publishing of books in indigenous African languages.

Armed with his first draft manuscripts of what would become the Wĩrute Gũthoma series, Kago approached Thomas Nelson and Sons publishers (now Thomas Nelson) in London who agreed to publish his books. During the holidays, he would find time to put together his manuscript for the three-book series and also write the teachers’ guides.

When he returned to Kenya, Kago was promoted to the position of African Inspector of Schools. This position gave him great influence as Kago had always been an advocate for the use of the mother tongue not just in schools but also at home during a child’s formative years. As he quickly rose through the ranks to join the Ministry of Education in charge of the teaching of indigenous African languages, Kiswahili, and religious education, Kago now had the power to not only directly influence how these subjects were taught, but also what learning materials the learners and teachers used.

It was while he was at the helm that the Kenya Institute of Education produced the TKK (Tujifunze Kusoma Kikwetu) series in various indigenous Kenyan languages including Dholuo, Ekegusii, Kikamba, Kalenjin, Kiswahili, Ateso, Luhya, Kigiriama and Kimeru.

Kago the man behind teacher training colleges

Kago was innately multitalented, versatile and an over-achiever whose hands left an indelible mark on whatever they touched, not just as a writer but also as a scholar, an education policy maker, and a teacher trainer.

Kago had begun his teaching career at his high school alma mater. In 1950, shortly after his return from England, he was posted to the teacher training college at Kangaru, in Embu, as the assistant area commissioner. What followed were a series of scholarships and subsequent promotions. A second scholarship to Santa Barbara in the US for a year in 1959 was followed by an appointment as Education Officer in charge of Kirinyaga District, and another scholarship to Australia for a course for school inspectors from developing countries in 1966 led to his appointment as the first African principal of Thogoto Teachers Training College a year later. He had served in an acting capacity at the same position in 1962.

As an educator, he had witnessed first-hand the dearth of textbooks in African indigenous languages.

Little is known of the close relationship between Kago and Kenya’s second president Daniel Arap Moi, and how a directive issued by Kago in 1949 while he was at the helm as an African Inspector of Schools would alter the course of Moi’s life. Moi was so indebted to Kago that in 1986 he directed that indigenous African languages be used in the early years of primary education.

Upon retiring from Thogoto Teachers Training College, Kago joined PCEA Hospital Kikuyu as a hospital administrator where he remained until 1976.

The controversial Beecher Report of 1949

Kago’s life was hardly linear or bereft of controversy. Like many Africans who received higher education during the colonial era, despite his belief in the use and teaching of the mother tongue in schools, Kago was a member of the Westernized African elite whose position and influence as an agent of the government was used to propagate the interests of the establishment as it weaponized education to serve the colonial agenda.

Following the paradigm shift in the colonial language policy after the Second World War, a committee headed by Leonard J. Beecher, a missionary, was set up. Much like the report of the Phelps-Stokes Commission and the Ten-Year Developmental Plan before it, the Beecher report of 1949 reinforced the argument for the provision of practical education for Africans, with an emphasis on vocational or moral training.

Moi was so indebted to Kago that in 1986 he directed that indigenous African languages be used in the early years of primary education.

At the time the Beecher report was being discussed for adoption and implementation, Kago had just been appointed as an African Inspector of Schools and he became one of its most vocal proponents.

In his PhD dissertation titled “Old Wine” and “New Wineskins”: (De)Colonizing Literacy in Kenya’s Higher Education published in August 2006, Dr Mwangi Chege, then a student of the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University, noted how, in a speech, Kago attacked Africans who viewed the “Beecher Report” as failing to address the literacy needs of Africans. Chege quotes Kago as having stated, in defence of the colonial government:

“You should realise the fact that all that Government wants to do is for our benefit and for the benefit of our children and we should unite together to build up a very good foundation right from the beginning and I am sure Government is ready to give us all the assistance we require.”

Chege’s critique of Kago was scathing:

“Thus, it is safe to conclude that Kago and his colleagues hailed the “Beecher Report” not because it was actually beneficial to their fellow Africans but because they were agents of the colonial system.”

In his book, A History of Education in Kenya, 1895-1991. S.N. Bogonko writes,

“The African view of the report was that it was to lead to Europeanization rather than Africanization of education and it sought to maintain the status quo of keeping Africans in low-wage positions. In addition, the report recommended that Kiswahili be the language of instruction and literature in primary schools in towns. However, provision was to be made for textbooks in indigenous African languages in rural areas and indigenous African languages were to be the medium for oral instruction in rural areas.”

The Beecher Report’s recommendations formed the foundation of the government’s policy on African education until the last year of colonial rule.

A hall with no hall of fame

Apart from the hall at the Thogoto Teachers Training College where there is a plaque with some letters missing, there is no hall of fame for Kago. Few in his hometown remember him or his contributions to his community, culture and the teaching fraternity.

The Beecher Report’s recommendations formed the foundation of the government’s policy on African education until the last year of colonial rule.

Most of Kago’s books have become so rare that they are now collectors’ items. Nelson East African Publishers (a subsidiary of Thomas Nelson & Sons UK) was acquired by Evans Brothers who later wound up their African operations in 2012. As Evans Brothers did not have any local shareholding, their entire catalogue went out of print, with the rights reverting back to the authors.

Little is left of the legacy of a man who always believed in the use of the mother tongue in schools and one who watched with dismay as English and Kiswahili took over as the languages of instruction in schools. Yet, Kago did prove that it is possible for our education system to implement the learning of African languages in schools; he created the blueprint for introducing indigenous languages as an area of learning in schools. If Kenya’s Ministry of Education is serious about actualising the National Language Policy within the competency-based curriculum (CBC), then they need not look too far.