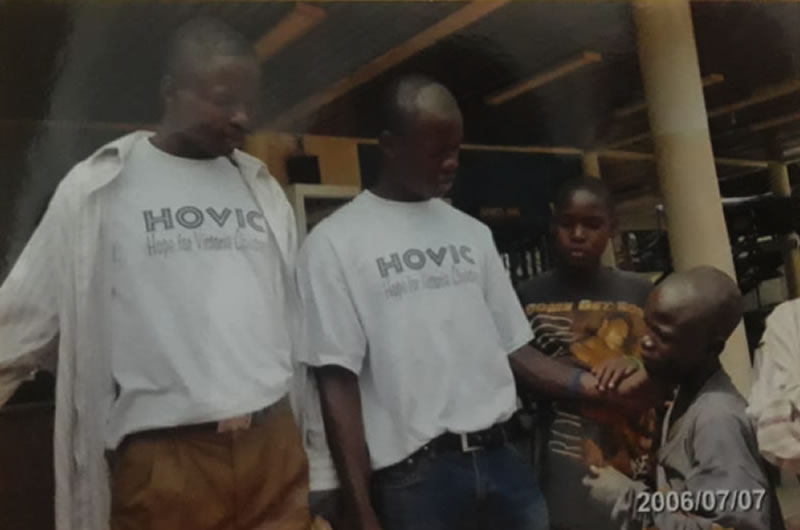

I met Isaac Juma in May 2006 at HOVIC — Hope for Victoria Children — a street children rehabilitation programme I was employed by as a social worker. HOVIC was established in 2002 to provide essential services to Kisumu’s street children as well as rehabilitate and reunite them with their families. While there has been no official census, it is estimated that there are anywhere between 250,000 and 300,000 children and young adults working and living on the streets of Kenya’s major towns and cities. When HOVIC’s drop-in centre opened its doors we had a running register of up to 400 children, with about 120 children visiting daily for food and various other services.

When the HOVIC programme started there seemed to be no methodology developed to undertake a census of Kisumu’s street children. A number of NGOs had tried to establish registers by organising parties at the Kisumu Sports Ground where the children and the youths would enjoy a meal and receive the gift of a t-shirt but these events always descended into chaos as fights broke out. To track the children we catered for, HOVIC created a database and register with the basic description and photographs of the children who came to the drop-in centre. The register was kept by a burly staffer aptly named Bouncer whose job it was to keep the children from hurting one another during the fights that frequently broke out at mealtimes. We had obviously underestimated the challenges of having in one closed environment hundreds of children and youths who were accustomed to solving their problems using violence.

I was fresh from university when I took the job at HOVIC, heading the rehabilitation programme. I was idealistic and overwhelmed by a strong sense of community and a desire to give back. The programme was run from the heart of Kisumu in an old concrete building that still harboured the ghosts of the one of the town’s first wealthy families. It was surrounded by Indian shops and open-air mechanics operated from a nearby Jua Kali yard filled with the carcasses of vehicles and ancient jalopies. The salary was paltry and any positive rewards of the job were counterbalanced by the depression that came with daily witnessing the reality of the children’s lives on the streets.

People brought their vehicles for repair in the sprawling yard. Women brought meat, tomatoes, onions and maize meal to the makeshift restaurants that dotted the yard. Crisp new notes and old ragged ones exchanged hands. Vehicles left happier than they had come. Some stayed longer. To be resuscitated or to die. Young boys, their bodies blackened by a life lived on the streets, collected the old oil that haemorrhaged from old engines. They scavenged discarded pieces of metal and plastic which they would take to the weighing scales of scrap metal dealers. All scrap metal had value but copper and aluminum were at a premium. On a good day, a kilogram of either would guarantee a meal. Plastic bottles were not of much value though; it would take hundreds of them to move the needle on the scale. The children moved through the sprawling yard like vultures, cleaning this ecosystem of waste. For food. For money. And for the occasional expression of sympathy.

Sympathy came mostly from people who had never before encountered humans in that state of existence. These people wondered what was wrong with the children’s homes, with their parents. How could they allow their children to wallow in waste? But expressions of sympathy were few and far between. More frequently, the street children were at the receiving end of the anger of those whose cars couldn’t be fixed quickly enough. Or who found the cost of repair too exorbitant. Or who felt that the mechanics were cheating them out of their money. Or those who simply needed someone to vent their frustrations on.

The locals called them Ninjas, for if they were not, how then could these children – some as young as five – survive their hard lives? How could they endure their pain without breaking? Their bodies absorbed the abuse hurled at them, and like human sponges, they soaked in the hate and the oil in equal measure.

Kisumu’s street children came mainly from Nyanza and the western region. Most were orphans, left under the care of relatives when their parents died from HIV/AIDS-related illnesses. Others had run away from violent parents and yet others to escape punishment from their guardians for petty crimes. But whatever the reasons, they all pointed to a deteriorating social order.

But even as the influx of street children grew, child protection services shrunk and soon the existing children’s homes within Kisumu could not accommodate them all. There are those who oppose the existence of children’s homes, believing that they act as magnets for street children, increasing their numbers on the streets. But from my experience, and having visited hundreds of families, the homes were sanctuaries for desperate children and filled the gap left by the government to provide child protection services. In effect, the government’s default setting was to send children to the Kisumu juvenile detention centre for crimes committed in the streets or for loitering in the streets at night before releasing them back into the very same streets with no attempt being made to locate their homes and reunite them with their families.

The hope was that the hardship suffered at the detention centre would act as a deterrent and motivate the children to return to their homes but my observation is that detention only hardened the children. To go through the police cells became a badge of honour and juvenile detention a rite of passage before the return to the streets.

In the meantime, the community hoped that the street children would one day disappear as if by magic, that the government would find a solution to the “menace”. Many were adamant that it was for the parents to take care of these children and hoped that this could be enforced legally to keep the children off the streets.

Instead, their numbers just kept growing. The streets provided these children with a space in which to discover themselves – through necessity and adversity. It could build them. Or break them. Had they been at home, chances were that they would be sober, in school, helping with family chores, teasing young girls at the watering hole while herding cattle. But instead they were here. And Kisumu streets were different and their darkness also different. It had teeth and it was biting off huge chunks of these children’s lives, leaving nothing but the basic instinct for survival. And hope.

The reality of street life was most manifest when night fell, when the good people retreated behind the reinforced doors that kept thieves at bay, that protected their television sets, their stereos, their microwaves, their flourishing lives away from the ghettos of Nyalenda and Obunga.

I once visited the places where the street children retreated to at night and found human beings folded into various shapes, bent into various forms, inside sacks that served as blankets and covers against the darkness and the mosquitoes, the full moon lending a surreal quality to the scene. They were lost in deep slumber, as if without a care in the world, some clutching plastic bottles to their breasts, the shoe glue that conjured up a more bearable reality, an alternative reality to help them navigate their waking nightmares and their sleeping terrors.

Some children were squeezed together into a single sack. Like twins in a womb. Forced together by circumstances not of their own making. Others had bigger sacks to themselves. Queen size sacks. King size sacks. Even here in the streets there was a hierarchy of power and influence. I looked over to Isaac, catching his face in the moonlight. This is how they start learning how to love each other. To protect each other. Brotherhood. This is also how they feel the initial warmth of their comrades. Kiss each other. Touch each other. Sometimes abuse each other, Isaac said matter-of-factly, pointing at the bodies that were tightly welded together in one sack. The older ones sometimes prey on the younger ones, Isaac continued, emphasizing each detail. As if concerned that I was missing important points.

Kisumu is hot. The ground absorbs heat from the sun like a loyal lover and when it is full, it vomits the excess heat into the environment. The doors of HOVIC would open to a frenzy of old faces and newcomers, each child bringing with him a thick layer of sweat from the heat and the story of their young life. The story of their families and their homes. Of a narrow escape from the police last night. Some came with fresh wounds inflicted by their peers. Or by the police. Or by dogs.

Others came high, floating on the cloud of euphoria that the shoe glue created in their minds. Glue was the street children’s opium. They bought it from cobblers who, like smalltime drug dealers, measured out glue meant for shoe repair into small bottles which they sold to the street children, a sticky yellow mess that seared the nostrils, numbed the brain and killed the hunger pangs and the pain. Sleep came easily, the hard ground now as soft as a downy mattress and safe as any home. Hypnotised into an alternative reality, they became quick to anger and violence was never far away.

One evening Isaac told me he had defaulted on his TB medications. He told me this with a smile on his face. Like it was something funny. I raised my head from my desk and asked him to repeat what he had said. “I have defaulted on my TB drugs. This is the second time I am defaulting.” Silence. I tried to look outside. I couldn’t see outside. The windows of my offices were so high. This building had not been built for office use. It had been built as a workshop for repairing old buses. “I know if I default again. I may get MDR-TB.”, Isaac continued. MDR-TB, multi-drug resistant tuberculosis, was wreaking havoc within Kenya’s healthcare system. I quickly made an appointment with the nurse who worked part-time at HOVIC.

Isaac could not keep track of his medication while living on the streets. He would lose his medication from the constant cat and mouse games with the police at night. On the other hand, the hospital needed him to account for every pill before he could get a refill. When he failed, they told him he needed to show up every day and take his pills at Kisumu District Hospital in the presence of nurses. And at each visit, he would have to go through the script of his life. And then the question he dreaded most would be thrown at him: “You are so smart. What are you doing in the streets? Why are you destroying your life in the streets?” He would soon get fed up and not go back.

To live, to survive, Isaac needed housing. Living on the streets is a complex affair. It gets even more complicated when one has a debilitating disease like TB. Survival starts with housing and food. We had figured out food. Children and youths could drop in at the rehabilitation center and get a warm meal. They could shower. The could get basic healthcare. But in the evening they would go back into the world, to the humming underworld of Kisumu Bus Stop. We needed safe housing.

There are many theories as to why children leave their homes to live and work in the streets. I have learned that it takes a lot for a child of seven years to decide to leave home for the streets. In one of the counselling sessions we held with the children, Isaac came along with a seven-year-old called Frederick Omondi. Or Freddie. Freddie had arrived in Kisumu from Gem. He had gotten into a matatu and somehow made it to Kisumu. He had never been to Kisumu before. He had no idea what Kisumu had in store for him. He was travelling by faith, the belief that a random stranger would hear his story and give him a chance at a life better than the one he was running away from. Isaac implored me to take Freddie home with me. I was living with my mother and my siblings. I obliged. Mostly out of fear for Freddie’s well-being than anything else.

Freddie’s home, like Isaac’s, was a world filled with nothingness. Freddie’s home had rocks. Big rocks. And his parents’ graves. His parents had died when he was very young. He barely knew them. He was left in the care of his uncle who, not knowing what to do with his life in that environment, resorted to drinking copious amounts of the local brew. I met him once. Drunk. Tall. Incapable of coherent speech. He was burdened by the loss of his relatives and took this loss out on his wife. Not knowing what to do, the woman took out her frustrations on Freddie. The cycle of violence was established. From the strongest to the most vulnerable. Until one day Freddie decided to run to Kisumu, and was brought to HOVIC.

Freddie’s journey to Kisumu was guided by a conspiracy of coincidences and good fortune. A lot could have gone wrong. He was lucky to make it to Kisumu with no bus fare. His aunt could have killed him. He could have ended in another town. He also arrived at a time when Isaac was friends with a young Australian man called Peter Dunkley. In his own unique way, Peter was looking to give back by helping to sponsor a destitute child. Isaac met Peter at Kisumu Sports Ground and struck up a conversation with him. The fact that all these random factors aligned is pure luck.

Isaac’s home on the other hand consisted of one room and one bed. His paraplegic brother, his other brothers, his mother, were all confined in this one tiny space. They were happy to see us. His paraplegic brother was trying to speak. His seizures were worsening and they were struggling to buy him the monthly supply of phenobarbitones. Isaac had also left home young. He wanted to save his family. He left to look for help.

People living in the streets are perceived as liars right from the word go. They don’t get the benefit of the doubt. Part of my job as a social worker was to conduct home visits. To witness and document the realities of the home environments and the circumstances that compel children to come to the streets. The realities of the homes the children came from always hit me hard, without warning. They came in the form of Freddie’s uncle. His alcoholism. In the form of Freddie’s aunt. She stood at a distance from us when we visited the home. In fear. Overwhelmed that the first white person she was encountering in her life had been brought to her home by a child she had persecuted violently. A child she had thought was long dead. What was the chance of that? It was a revelation of biblical proportions to all of us. We decided that Freddie was not remaining in that home.

The image of Isaac’s paraplegic brother brought home to me the reason for Isaac’s decision to leave home. Risking everything. Leaving the love of his family and abandoning some degree of predictability within the confines of poverty, for the unknown of the streets. He was barely a boy. What have we become as a society? Why does it take us so long to see that it takes a lot for these children to be on the streets? To put their lives at risk? It certainly wasn’t for fun. Or for adventure. These children had seen things we have not seen. The nightmare they faced on the streets was in many instances lesser than the nightmare they faced at home.

I have since stopped slicing up my brain trying to understand these children and I feel no shame in keeping the company of those who have spent a part of their lives in the streets.

It’s the 23rd of July 2019. I am seated across from Isaac in his house in that concrete jungle teeming with humanity that is Kahawa West. Isaac is talking to me about politics. His time abroad. His work at an international NGO, and his plans to finish his post-graduate degree at the University of Nairobi. I am not sure what would have become of Isaac or Freddie if they had not made the decision to run away from home and seek help in the streets.

But Isaac and Freddie are exceptions. They had the will to stay away from drugs and from the other temptations of street life. Isaac had a very clear vision of who he wanted to be, and how his success would be channeled to help his family. He has achieved that vision. Freddie is on track to achieving his vision too.

I still encounter some of those who were on the streets with Isaac and Freddie back in 2006 and 2007 every time I walk down Oginga Odinga Street. They are now adults. Many of the others have died; killed during the cycles of post-election violence or succumbed to disease or drowned in Lake Victoria. A few lucky ones were helped to return home by relatives or well-wishers, or through street children programmes.

I cannot point to one singular factor that would explain why some make it out of the streets and others do not, except perhaps a chance encounter with the right people, a strong will to survive. And luck.