In an interview on Chimurenga’s Pan African Space Station radio back in 2017, celebrated South Sudanese essayist, poet and scholar Professor Taban lo Liyong’ was asked by the interviewer to give his thoughts on the famous first African Writers Conference that took place on June 1, 1962 at Makerere University, Kampala. Taban, whom I fondly call the ‘poetrigenarian’, did not mince his words. He quipped that the Conference of African Writers of English Expression, as it was dubbed, not only isolated East African writers but also snubbed African writers who had published their works in indigenous languages. He went on to observe that Ugandan poet Okot p’Bitek “invited himself” to the conference while Ngugi wa Thiong’o – then James Ngugi, attended it, not as a writer of fiction but as a journalist. At the time, Okot had published Lak Tar (White Teeth) in Acholi while Ngugi would proceed to give his The River Between manuscript to Chinua Achebe at the conference, a book that the South Sudanese interestingly describes as “algebraic” as it is “the writing of Achebe’s Things Fall Apart in the Kenyan context”.

Taban further observed that the isolation of East Africans from a conference that occurred right on their territory was meant to “shame them into writing since East Africa was a literary desert at the time”. But Taban was particularly disturbed by the deliberate move to lock out African writers who wrote in their mother tongue. In so doing, the Western organisers of the conference simply told Africans that English was superior to African languages and had a special place in the land they had colonised.

Ironically, it was after this conference that Nigerian scholar Obi Wali published his controversial essay titled The Dead End of African Literature in which he argued that “an African writer who thinks and feels in his or her own language must only write in that language”. English, he argued, did not have the capability to “carry the African experience”. Some of the writers like Achebe argued to the contrary that Africans could Africanise English to authentically convey our cultural truths. But Wali’s paper inspired young writers of the time, notable among them being Ngugi wa Thiong’o who went on to become one of the chief proponents of writing in indigenous languages.

Mukoma wa Ngugi, in What Decolonizing the Mind Means Today, an article published in Literary Hub in June 2018, echoes his father’s views when he observes that the relegation of African languages in the post-colonial literary space influenced Ngugi to publish Decolonizing the Mind: the Politics of Language in African Literature in 1986. In the work, Ngugi rightly spiritualises language as culture and demonstrates its critical role in the decolonisation of the mind.

Earlier in 1966, Ngugi together with Taban and p’Bitek led other scholars at the University of Nairobi in pushing for the abolition of the then English Department and its replacement by a new department that would open up the study of literature to African literature and literature from other cultures. Indeed, the Department of Literature was finally established by the university and this saw the introduction of courses like East African Literature.

It’s more than half a century since these writers challenged the colonial hoisting of the English language post the fall of the Union Jack. Today, the University of Nairobi’s Education Building hosts, among other departments, three key departments that teach languages and literature: the Department of Literature, the Department of Linguistics and the Department of Kiswahili. In major universities across Anglophone Africa there exists a department that teaches African Languages, notable among them being Makerere University, University of Botswana, University of South Africa, Wits, Stellenbosch and University of Zimbabwe, among others. In these universities, post-graduate students are at liberty to identify and conduct research on any language or literature of their choice, including indigenous knowledge systems.

It’s safe to say that the rise of African languages and literatures in African universities is something that should be treasured. However, it’s hard to identify any palpable influence beyond the theoretical walls of academia. In fact, there is every indication that we have come full circle, and despite academic research in universities, mother tongue languages are increasingly being abandoned, mostly by educated native speakers in cities and towns. In particular, Generation Z or Gen-Z (described by the BBC as anyone born after 1995) represents a generation that can hardly communicate in their mother tongue. A majority of Millennials (the generation preceding Gen-Z) are equally unable to speak their mother tongue. The only difference is that the former are generally apathetic – if it’s not technology or social media, it’s not worth their time.

UNESCO observes on its website that Sub-Saharan Africa is one of the three regions with the most endangered languages, the other two being Melanasia and South America. But Sub-Saharan Africa has a special relationship with French just as it does with English and Portuguese. According to a report published by Quartz Africa in October 2018, French is now the world’s fifth most spoken language “thanks largely to the millions of Africans who speak it each day”. The report states that 35% of the three million French speakers are from Sub-Saharan Africa while Asia only accounts for 0.6%. Interesting.

There is every indication that we have come full circle and despite academic research in universities, mother tongue languages are increasingly being abandoned

In the meantime, African languages are falling off the scale. UNESCO’s Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger 2010 observed that Sudan had the highest number of endangered languages, a total of 65; Cameroon was second with 36; and Nigeria tied with Chad at number three with 29 endangered languages. Kenya was third from last with 13 endangered languages; with slightly more than 60 indigenous languages in the country, this is tragic. In Kenya, languages like Burji, Suba and Boni are considered endangered while Yaaku and El Molo have been declared extinct. These deaths occur more as a result of political rather than natural causes.

The cemetery of dead languages may have no physical graves or tombs but it surely is just as unnervingly silent as the human cemetery. These languages are buried in the minds of native speakers as a memory of an empty epitaph – one that cannot be understood, retrieved and passed on to the next generation.

Long before we began committing linguicide (death of a language), the colonial masters knew how valuable our indigenous languages were to us and ensured that they colonised us culturally by perpetuating injustices against our languages. Through subjugation, slavery and total dehumanisation of Africans, the colonial master succeeded in creating an image of Africa and Africans that couldn’t exist independent of the colonial crown.

Every country had its fair share of colonial experience. In most of these countries, the colonial experience created a black mzungu (Englishman/woman) out of the educated class and those born afterwards inherited the primitive worship of mzungu as superior to us.

UNESCO’s Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger 2010 observed that Sudan had the highest number of endangered languages, a total of 65

In Kenya, the black mzungu syndrome is linguistically evident in our collective response to the misguided belief that the English language is superior to our indigenous languages including Kiswahili. To be educated in Kenya is to speak good English; you are a genius if you speak the Queen’s English. English is a key metric of academic excellence. Woe unto you if you speak English with your mother tongue accent, even though Kenyans admire Russians when they speak English with a Russian accent and are glued to their TVs when an Italian speaks Swahili or Kikamba with an Italian accent. Those of us who stay in America for a minute land back home with an American “accent” that openly clashes with our mother tongue accent. To sound American is to sound polished.

But our love for foreign accents strangely isn’t limited to the West. I have come across Kenyans who while they shame or bully a fellow Kenyan on social media because he or she speaks English with a heavy mother tongue accent, delight at and in fact mimic with admiration how, say, South Africa’s Economic Freedom Fighters leader Julius Malema says “Mama, give us a signal”. Somehow, it doesn’t bother them that Malema’s accent is influenced by his mother tongue, and he’s perfectly proud of his mother tongue just as other South Africans probably are. The same thing can be said of our celebration of Nigerian pidgin. Clearly, our disdain for how we speak English points to an identity crisis we host in our bodies. It has appreciably affected how we relate with our mother tongue languages and with one another.

Some of the Millennials and Gen-zers attempt to justify this disdain by claiming rather erroneously that indigenous languages are a cause of disunity in pluralistic societies like Kenya. Yet inter-ethnic hostility is not a function of one’s language. Rather it is a by-product of misguided tribal attitudes characterised by hate and insecurity. But it is not surprising that these two generations cannot appreciate the place of the indigenous language in their culture; the education system never trained them to. It is proof that learners in our schools deserve a system of education that destroys the black mzungu mentality and enables them to creatively learn their mother tongue, particularly in lower primary school.

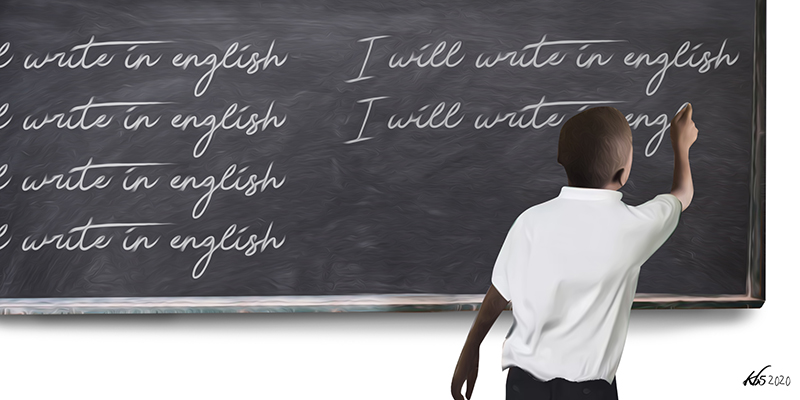

In 2019, a Member of the Nairobi County Assembly, Ms. Sylvia Museiya, sought to introduce a Bill in the County Assembly to make learning the mother tongue compulsory for Early Childhood Development learners. She proposed that parents be compelled to teach their children their mother tongue at home with the learners then expected to speak the language in class. Ms. Museiya’s concern came from the fact that most children in Nairobi cannot speak their mother tongue and their parents seem to be the enablers of this self-inflicted injustice. One may not approve of her approach, but there is consensus that there exists a problem somewhere. Ironically, while learners in Nairobi are soon being forced to learn to speak their mother tongue, learners in rural schools have always been punished for speaking their mother tongue. In my formative years, we had the dreaded “disc” – a physical object that pupils hung around their necks whenever they were “caught” speaking their mother tongue. Same system of education, different motivations. In one, the city parent is guilty, in the other, the rural teacher is.

Post-colonial scholars questioned and sought to dethrone colonial ideologies that shaped education and gave learners a false consciousness through “internalisation of the image of the oppressor” and the oppressor became “the model of humanity” for learners as Brazilian scholar Paulo Freire observed in his influential work Pedagogy of the Oppressed.

As post-colonial scholars sought to install the indigenous language at the center of literary and linguistic studies in our universities, the education system of the time was already dehumanising learners in primary school with a warped philosophy that radicalised learners into disowning their languages. Metaphorically speaking, post-colonial African scholars prepared the way but no one really showed up; young learners had been directed the other way.

Over time, our society and its political body parts (citizens and institutions) have become more culturally unconscious in a world that is fast changing. Consequently, identity becomes loose if not nebulous since people are generally learned but not necessarily educated. This lack of cultural consciousness is proof of failure on the part of our social institutions and explains why over fifty years later, we are still debating whether we should write in our indigenous languages.

Nonetheless, I find it grossly unfair to assess the African writer’s commitment to his or her culture based on whether he or she has authored works in his or her indigenous language. As much as an indigenous language enables its speakers to authentically express their truths and values, these truths and values may still be expressed in a foreign language. Achebe’s Things Fall Apart back in 1958 and Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor’s Dust fifty years later are just but a few demonstrations of this possibility.

This view is not to be interpreted to mean that a foreign language can usurp (violently or on the pretext of conveying a people’s truths) the cultural power of an indigenous language. Foreign languages shouldn’t be made or be seen to compete with indigenous languages because they actually can co-exist. They should not be considered as alternatives to the existence of any indigenous language.

There wouldn’t be a better time than the time when Africa starts to produce just as much writing in indigenous languages as in foreign languages. But how would it be possible if African governments do not devotedly invest in their languages and cultures? How would it be possible if the West that controls the African fiction enterprise continues to respond to the demands of their (Western) market? How would it be possible if the 21st Century African writer is blamed for a problem that is clearly not of his or her own making?

It is not enough for the older generation of African writers to simply cheer younger African writers into writing in their mother tongue. In fact, it would be a catastrophic failure on the part of the former if they didn’t appreciate that writing in indigenous languages is dependent on various dynamics and thus cannot be resolved by merely “encouraging” the younger generation of writers to write in their mother tongue.

First, take for instance the cancer of cultural illiteracy that prevails in our society today. We live in a society that perpetuates, against itself and its own offspring, the colonial and neocolonial ideologies. It’s a generation of culturally illiterate learners who are hardly interested in literature published in their indigenous languages. If they don’t speak it, either because they can’t or because they don’t want to, will they read it? In this environment, the African writer of mother tongue fiction isn’t guaranteed returns and thus has every right to choose a language that guarantees financial reward. Writing is not martyrdom.

Sadly, this cultural illiteracy is sustained by a snobbish political class that clings to the traditional hierarchical exercise of power through domination and thus is antagonistic to open and truly participatory policy-making processes that involve stakeholders. The recent contentious implementation of the Competency Based Curriculum (CBC) that replaced the 8-4-4 system in Kenya amply embodies this problem.

Secondly, textbook publishing has bedeviled the growth of fiction in Kenya. In a country where publishers are motivated by profits, fiction writers are bound to struggle to get their work published. It can only get worse for writers of mother tongue fiction. In an article published in The Elephant titled African Publishing Minefields and the Woes of the African Writer, Kenyan author Stanley Gazemba lays bare the inability of the local publishing industry to support the growth of fiction. He observes that the local publisher is profit-motivated and would rather invest in publishing books for schools than take a leap of faith into works of fiction. These publishers fundamentally publish fiction for speculation; if they don’t see a set book or a school reader in a writer’s manuscript, they’ll most likely not publish it. It’s for this reason that the African writer turns to foreign publishers, which as Gazemba observes, is a difficult expedition.

It’s a generation of culturally illiterate learners who are hardly interested in literature published in their indigenous languages

But the reality is that it’s rare to come by foreign publishers interested in mother tongue fiction. Those that are will ask for a translation (to see if it meets their threshold, and fits their style and audience) and the assessment will most likely be based on the translation, not the work in its original form. Not even the many online literary journals and magazines that dominate the African literary scene today are actively publishing works in mother tongue save for a few editions here and there. In 2016, for instance, Jalada translated into over 30 languages Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s Gikuyu fable The Upright Revolution: Or Why Humans Walk Upright. In an interview with the Guardian newspaper, the then Jalada Managing Editor Moses Kilolo said Ngugi was “uniquely placed to be the first distinguished author and intellectual featured in our periodical Translations Issue”. During the 2017 Caine Prize Writers workshop in Tanzania, the Director of the Prize, Dr. Lizzy Attree, commissioned the translation into Kiswahili of selected excerpts from Lidudumalingani Mqombothi’s “Memories We Lost”, Lesley Nneka Arimah’s What it Means When a Man Falls from the Sky and Abdul Adan’s The Lifebloom Gift. Such projects are expensive and are isolated cases on the continent; it explains why I can’t seem to find Jalada Translations Issue No 2 four years later. Away from this, there’s hardly any fiction published today in indigenous languages in Kenya, besides Kiswahili which is one of the two official languages.

In my early school years, I came across a number of Dholuo stories that are mostly out of print today. These included Otieno Achach, a classic by Tanzanian writer Christian Konjra Aloo, published by East African Publishing House in 1966; Masira ki ndaki (Misfortune is Inevitable) by the late Professor Okoth Okombo, Miaha by Grace Ogot (later translated as Strange Bride by Okoth Okombo). Asenath Bole Odaga perhaps stands out as the greatest contributor to Dholuo literature, with works varying from short stories and oral literature to an English-Dholuo dictionary. It would be accurate to say that, unlike today, publishers of the time embraced mother tongue fiction..

Without a doubt, because of these dynamics, the African writer may lack the motivation to write or even translate works of fiction into his or her indigenous language. The popular line has been that writers should be left to choose their preferred language of telling their stories, a position that I do not have a problem with. However, it’s reasonable to argue that our choices could have been different if our collective experiences had been better. It would help if we held the political class accountable for their cultural sins of enabling cultural servitude through neocolonialism and moral corruption in independent Africa. In so doing, we can reward ourselves with the opportunity to redefine the determinants that govern the choices that this and the next generation will make. This is a critical stepping stone to a more sustainable conversation.

At the risk of sounding academic, Sun-ki Chai, in a paper titled Rational Choice and Culture: Clashing Perspectives or Complementary Modes of Analysis, reports that individuals’ actions usually are “dependent on preferences that are determined by socio-psychological factors” and that “culture plays a role in shaping the behavior of rational individuals”. In this context, the African writer’s choice to write in a foreign language is influenced by his or her past and present environment.

In light of this, it is necessary that the society interacts with its past and present to eliminate encumbrances that stifle the growth of indigenous languages in all forms. These hindrances are more political than we would want to imagine. Since politics can be complex and subjective, the solution will not come from simply promulgating one policy after another. The “African society” must hold conversations with itself and overhaul its value system, because language is culture, and culture is empty without its set of values and truths.

Since politics can be complex and subjective, the solution will not come from simply promulgating one policy after another

Finally, an anecdote. I once bumped into a professor of Literature along the pavements of University of Nairobi. The professor was chatting with a female colleague and I gathered he was trying to speak to the lady in her mother tongue which was not his mother tongue. She kept smiling. The professor then went on to wittily tell me he was trying to “speak to her heart”. He said that when a man speaks in English to a lady whose first language isn’t English, he speaks to her head; but when he speaks to her in her mother tongue, he speaks to her heart. In our case, the lady goes by the name Africa. She may understand English, French or Portuguese, but I’m sure she misses mother tongue stories and the poems of the African writer audibly flowing in the calm beat of her heart.